2025 WINNERS

STUDENTS

2025 Edition

First Prize Poetry in Spanish

La moneda del tiempo

Author: Edoardo Nicotra Menéndez

Dual Degree in Business Administration and Laws

La moneda del tiempo

No sé con qué moneda

pagará mi boca

la deuda del tiempo.

¿Acuñaré silencios?

¿Fundiré esta sed

en metales vencidos?

El desierto araña mi garganta.

Busco agua,

pero el pozo devuelve

un retrato de sal.

Ignorancia: mar sin barcas,

sin islas,

sin otra orilla que esta hambre

de nombrar lo que ignoro.

La vida es un filo

envainado en preguntas.

Calderón lo supo:

actor que sueña escenas

en un teatro sin butacas.

Yo,

fantasma con pasaporte de arena,

bebo minutos

como quien sorbe veneno

en vasos de cristal frágil.

Y cuando el tiempo reclame,

le mostraré mis labios llenos:

las risas que sembré,

los besos que no medí,

el veneno que bebí como vino,

y este instante desnudo

donde bailé con la sed.

Y el viento, escribano de lo que no perdura,

firmará la paz entre nosotros.

Yo, borracho de ahora,

saborearé lo ignoto como pan de oro

y en el filo de la ignorancia,

encenderé una hoguera con las preguntas sin nombre.

Second Prize Poetry in Spanish

Para mi abuelo

Author: Juan Pablo Gonzalez

Bachelor in Behavior and Social Sciences

Para mi abuelo

Yo nunca me senté en tu regazo

para que me leyeras un cuento

Nunca me llevaste a comer helado

Nunca te pedí un consejo

Pero te miro a los ojos y veo los de mi madre,

y los suyos como los míos,

bajo el sol se tornan olivas.

Miro tus fotos y pienso en Verónica

sonando en tu tocadiscos,

y veo los años que viviste alejado de ella,

y veo cuánto la quieres.

Te miro, veo a tu padre y vislumbro Cuba,

la trova y la costa soñadora de esa isla

-¿algún día la visitaste?-

Y ¿tú conociste a tu abuelo?

Third Prize Poetry in Spanish

Domingo

Author: Beatriz Sánchez del Río

Dual Degree in Laws and International Relations

Domingo.

Cedió la madera como el trigo. El viento del grano se coló dentro. Liviano y seco, autoritario. Compasivo. Tostado. La luz reptó hasta su mirada: dorado sobre dorado, calor bajo calor. La tierra entre sus rayos, los pájaros tras su silencio. la brisa surcaba las astillas, ignorante de la tierra, apenas consciente del silencio, independiente de su mirada.

Qué le diría al algodón que ocultaba fervientemente el calor, aquel que le prometía lo pardo, lo salvaje e infértil. Caprichoso. Cómo podría espantar la humedad que tanto ansiaba anidar a la sombra de su ventana.

Sembraba la despedida, pese a la previsión de plagas, esperanzada por la certeza tajante de lo que crecía más allá de la madera.

El vidrio terminó por viciarlo, aunque no lo nublara. Se esfumaron los silencios y las astillas como se escondía la ignorancia de la tierra. Así se sucedían las estaciones.

Cómo envolvería la flor y plegaría el fruto, cómo atraparía el aroma y la carne, cómo se atrevería a arrancarlos de su tierra con la crueldad con la que se habían podado sus propias huellas.

No le quedaría más que asfalto al alejarse de la madera, y el vidrio permanecería en su memoria como un inofensivo fango, abnegado ante lo cristalino.

No quería imaginarse los alaridos, la sangre seca (que ni vivía ni lo había hecho nunca, que sólo abastecía patas con dueño, pero sin aliento), la convicción de que el oxígeno se esfumaría sin llegar nunca a las hojas.

Qué opción le quedaba, sino arrancar un pedazo de tierra que consiguiera que sus alas, migrantes, fueran más ligeras.

First Prize Poetry in English

Segovian Summer Snow

Author: Tom Hinderoth Zachrisson

Bachelor in Business Administration

Segovian Summer Snow

And one evening, as I walked beneath the ancient ribs of the aqueduct,

I beheld the sun falling not with fury, but with forgiveness.

And it spoke unto the stone: “You have endured and so shall he.”

And I knew it spoke of me.

For in Segovia time does not pass — it listens.

It listens to the breath of youth in study and laughter,

to the footsteps of the stranger who becomes familiar,

to the silence of snow that falls when none is watching.

But lo, it was not snow as I knew it in the North —

Not the frost that blinds the fields of childhood,

nor the white hush that silences the soul —

It was a snow of the spirit,

a snowfall that melts even as it touches,

leaving no trace but change.

And I said:

“Is this not the way of all learning,

that it arrives not as fire, nor as wind,

but as snow in Summer —

quiet, uninvited and inevitable?”

In this city of stone and sky,

I have tasted the patience of old walls,

and the urgency of fleeting time.

I have sat beside fountains where past and present drink from the same cup,

and I have written my name in water,

so that it may disappear — and be remembered.

They asked me:

“What have you gained in Segovia?”

And I said:

“I have lost nothing but illusion,

and gained only what cannot be measured —

the gentle certainty that I am becoming.”

And when I shall leave,

as all pilgrims must,

I will not carry souvenirs,

but the echoes of the church bells at dusk,

the heat of stone that remembers,

and the summer snow that once fell upon my soul.

Second Prize Poetry in English

Three

Author: Laura De Remedios

Bachelor in Philosophy, Politics, Law & Economics

Three

I barely write now;

I leave that for sadder days.

How many days a week can one be sad?

I say three.

But some weeks I indulge and do a fourth.

On my desk, half a poem more —

and the wish to forget who it’s for.

Next week, only two days, I say.

The wallet near my ribs grows thin;

and I still haven’t phoned my friend.

So I walk past my notebook—indifferent,

skip the incense, skip the chamomile tea,

ignore the rhymes I might stumble b-, across.

Not today! I shout to my pens.

How many days can a hollow hold?

Come to think of it, three might run short.

It's only noon and I’ve already spent

more than I can afford.

Third Prize Poetry in English

The Wall Between US

Author: Connie Ganburged

Bachelor in Behavior and Social Sciences

I used to build walls with my mother tongue.

A quiet fortress of caution for anyone who spoke in a beat not mine.

Colored eyes felt like mirrors in which I couldn’t see my reflection.

I feared what they would see, or worse, what they wouldn’t.

I thought love needed translation.

That something about me would always be too much, or not enough to cross the gap.

Then you came, not with poetry or promises, just presence

Brief, inconsistent, but enough.

You didn’t love me, but I let my wall fall anyway.

You used me, and I mistook that need for care.

I let my guard down not for love,

But for the chance that I could feel without fear.

Now you’re drifting, a silence heavier than any language barrier.

And I wonder,

Was I wrong to open the gate for someone just passing through?

Maybe the wall kept me safe.

Maybe the wall kept me lonely.

Maybe now,

I’m somewhere in between, bricks in hand,

But unsure whether to rebuild or leave the ruins as they are.

First Prize Short Story in Spanish

Fugu

Author: Pablo Íñiguez de Onzoño

Dual Degree in Laws and International Relations

FUGU

Demasiado tarde, pensó el candidato, aunque había llegado 15 minutos antes. No había vuelta atrás. Con nadie más para hacerle compañía que un camarero en pausa echándose un cigarrillo, el candidato vio esta ocasión como la más apropiada para repasar todo lo que se había preparado. Su currículum no era del todo inapropiado para el puesto: a su carrera de data y finance se le añadía un periodo de prácticas en el prestigioso banco Herman & Associates y un manejo profesional de Excel, Perplexity y otras herramientas digitales. Pero ningún repaso de su trayectoria profesional podía despojarle de la extraña situación a la que había llegado 15 minutos antes. Tras haber estado en interiores impolutos, forrados de madera falsa y oficinas asépticas, encontrarse en un callejón maloliente y descuidado no era el escenario que esperaba para la última fase del proceso. Y ahora que sentía sequedad en la garganta, le dio rabia haber rechazado, por mera cortesía, tantas botellas de agua artesanal cristalina de la oficina en las cinco ocasiones en las que había pisado la sede corporativa. Pero el mensaje era rotundo. “22:00 pm en el Kabuki, callejón entre la calle Oeste y la 57”. Sobre todo cuando viene del CEO y fundador de la empresa. Qué leches hago aquí, se dijo el candidato, mientras apartaba con el pie un papel que volaba con pegajosa voluntad hacia su traje de franela. Pensó si no le habrían hackeado el correo y citado en aquel callejón de mala muerte para atracarlo, pegarle una paliza o Dios sabe qué. Ciertamente, tal y como iba, era como si una gacela fuera a una manada de leones a preguntarles la hora del almuerzo. Pero según su contacto en la empresa, el fundador era una persona peculiar cuanto menos: nunca iba y venía a la oficina por la misma ruta, prefería en ocasiones la escalera y encontraba siempre otras formas de saltarse cualquier protocolo de la jerarquía corporativa. Viendo el siniestro concierto de olores a frito, basura y otros despojos de trastienda que le rodeaba, el candidato dudó de si aquello no sería una broma más que otra cosa. Sin embargo, el luminoso le recibió con un parpadeo mortecino, “Kab ki”. Bueno, faltaba la u pero era el sitio. Con el rostro parpadeando intermitentemente del rojo y morado del letrero, esperó pacientemente al que tenía que ser el maestro de ceremonias de aquella noche. Hombros abajo y atrás y pecho hacia adelante, power pose para dar su mejor impresión al creador del sistema operativo más avanzado del mercado y con ello tener la preparación mental requerida. No sabía cómo iba a ir la reunión, por donde irían los tiros. El candidato entendió la espera como el momento de que el restaurante se presentara. El Kabuki, también llamado Kab i o Ka uki – dependiendo de cuál de las letras del luminoso fallaran – era un estrecho local amueblado con dos mesas, varias sillas y una barra, paredes de blanco desgastado, con un fuerte y pesado aire a pescado y fritura como fragancia, y con la peculiaridad de tener la entrada donde otros restaurantes tenían la trastienda.Second Prize Short Story in Spanish

La historia del perro

Author: Rie Boe Pedersen

Executive MBA 2021 - 2022

La historia del perro

Me llevo la libreta, y bajo al Café Bancarrota. A veces viene bien salir un poco de casa, para airearte la cabeza. Desbloquearte. Llevo con este guion dos meses. Es el camarero de algunos otros días, el bizco. Siempre dice eso, “excelente elección”, cuando pido. Le parece muy divertido, aunque finge decirlo en serio. No le digo nada para que no quiera decirme más. Me pido un café con leche. Suelo pedir eso. Si es tarde, un agua con gas. “Excelente elección”. Hay dos mesas en los ventanales. Son las que yo quiero. Me gusta poder mirar por la ventana y sentir que formo parte de cosas que ocurren en la calle donde apenas pasan coches. Sin tener que mezclarme con nadie. Este día una de las mesas está ocupada por dos mujeres jóvenes. Peligro. Parece que llevan tiempo instaladas allí. Pero aún pueden tener cosas que contarse. O no tienen nada que contar y aun así hablan, ya rebuscando entre lo residual que suele ser donde está lo peor del ser humano. Termino optando por mi sitio habitual, con el ventanal. Es bueno tener costumbres, y yo tengo mis cosas que hacer, mi escena a resolver. Me trae el café el bizco. “Tu café.” No sé en qué momento se perdió el uso del usted. Acaso piensa que por venir a menudo busco que me traten como si fuéramos amigos. El café aquí está bien. Lo sirven en una taza grande. Te ponen una galleta. La dejo para cuando me queda una tercera parte del café. Es como un premio, pero no es el final. Es como el segundo punto de giro del guion, luego aún queda tiempo para resolver los últimos flecos. Me he quedado en la primera escena de la piscina. Cuando mi protagonista es joven y la ve por primera vez, con su esbelta silueta, en bañador. La ve sólo desde atrás, pero sabe que esa es la mujer de su vida. ¿Entonces por qué no hace nada? ¿En ese momento vienen sus amigos y se lo llevan? Podría simplemente oponerse, a no ser que se lo llevaran a la fuerza. Si son amigos, tampoco lo forzarían con violencia. Quizás piensa que ya la volverá a ver porque estará por allí. Por eso se deja convencer por los amigos. ¿Y cómo transmito que él piensa eso? Las voces de las mujeres en la mesa de al lado invaden la escena como una radio demasiado alta al lado de la piscina. Si fuera en el rodaje alguien gritaría “corten” y habría bronca. ¿Por qué tienen que hablar tan fuerte? Están a 30 centímetros una de la otra. ¿No se dan cuenta de que, para entenderse, con la mitad del volumen bastaría? ¿Por qué no pueden tener la consideración de no ocupar todo el espacio con su nada interesante conversación que podría perfectamente nunca haber existido? Levanto la cabeza de la libreta varias veces de forma brusca para que el movimiento les llame la atención, pero ni lo registran. Intento volver a mi escena, pero es imposible ignorar la maldita emisora de insignificancias. —Yo no estoy buscando compromiso, eh. Vamos, lo tengo clarísimo. Si podemos estar así, por mi bien. Pero, vamos, que tampoco tengo yo la sensación de que es el príncipe azul, ¡eh! O sea: muy bien. Pero, vamos, que lo que dure. Ya está. Me han fastidiado el café. No voy a progresar. Nada, tiempo perdido. Puedo terminarlo e irme. O quedarme aquí escuchando sus banalidades. Porque no hay otra opción. Si estás aquí sentada, estás condenada a estar en su conversación. Las dos cotorras se han apoderado de este espacio. —¡Sí! Ya no está con Isma. Se divorciaron. —No tenía ni idea. —Fue después de la pandemia. Él había tenido un affair. ¿Y sabes cómo se enteró Elena? Por el perro. ¿Recuerdas que tenían un retriever precioso? —Claro, Silas. —Pues, durante la pandemia Isma lo sacaba a pasear. A ver, lo normal. Supongo que al principio lo sacaban turnándose. Pero bueno, en algún momento empezaban a distribuirse un poco las tareas porque al niño tampoco se le podría dejar solo, y Elena no veía mal que lo sacara Isma cada vez. »Y lo sacaba bastante. Mañana, mediodía, después de comer, a eso de las seis y luego sobre las diez. Es verdad que, ahora que podían… Al perro le venía genial. Y también era una forma de abstraerse. A Elena en ningún momento le había extrañado nada. Es verdad que algunos de los paseos eran bastante largos. A veces no estaba muy claro si el paseo de después de comer se fusionaba con el de la tarde. Pero también había días que hacía bastante buen tiempo y a lo mejor Isma aprovechaba para sentarse en un banco o algo. Bueno, todo eso creo que Elena no lo pensó en su momento, sino luego de forma retrospectiva. Me encuentro mirando fijamente a la mujer que cuenta. Veo de perfil su boca por la que sale esa voz que corta el ambiente como si fuera un cuchillo. En ningún momento han dado señales de notar que estoy allí, pero aun así bajo la cabeza y pongo el boli sobre el papel fingiendo estar entregada a lo mío, aunque en realidad estoy dando vueltas dibujando un círculo. —Una vez que terminó el confinamiento y poco a poco íbamos volviendo a la normalidad él mantenía los paseos largos. Hombre, ahora iba más a la oficina, y también empezaba a haber más gestiones llevando a Lucas a cosas y demás. Pero bueno, todos adquirimos nuevas costumbres durante ese tiempo. »Hasta que un día pasó algo supersuperraro. Habían ido los dos a una pescadería. Y estaban dentro esperando su turno. Y en ese momento entró una mujer. Mi círculo sobre el papel de repente se acelera y se convierte en unos rápidos apuntes: “pandemia - empieza a dar paseos cada vez más largos - mujer bella…” Vuelvo a subir la mirada para no perderme detalle. —Elena realmente no estaba mirando la puerta de la tienda, pero vio cómo de repente a Isma se le cambió totalmente el gesto de la cara y se giró mirando el género. Por eso Elena buscó qué había pasado y vio que la mujer también por un momento se paró en seco, pero entonces terminó de cerrar la puerta preguntando al último por el turno. En ese momento Isma empezó a hablar de diferentes opciones de pescado que podrían comprar, aunque desde el principio sabían que habían venido por salmón. …Que si hacía mucho que no tomaban lubina, ¿cuándo fue la última vez? Y que si alguna vez habían hecho sepia en casa. La otra mujer se ríe. Yo también sonrío mientras escribo. —Elena estaba tranquila. No entendía muy bien qué le pasaba, pero enseguida les atendió uno de los dependientes y las tres rodajas de salmón ya estaban cortadas, así que no tardaron. Isma pagó rápido. Tan rápido que se le cayó una moneda allí entre los trozos de pescado expuestos. «No pasa nada» exclamó y le dio otra moneda por la que faltaba y ya se fueron rápidamente. »La mujer ya pasaba a ser atendida en la otra cola y Elena se fijó en que no les volvió a mirar, así que pensó que, si es que se conocieran, desde luego estaba claro que no querían saludarse, y que ya se lo contaría Isma. Apunto todo para no perderme detalle ya que está bastante clara la situación. —Pero no te lo pierdas, tía. Pausa dramática. Vaya par de cotillas. —Están fuera de la tienda. Elena desata a Silas que estaba esperándoles y empiezan a alejarse. En ese momento sale la mujer con su bolsita de pescado. Y de repente Silas se suelta de un tirón que le pilla totalmente de sorpresa a Elena. Por un momento piensa en que tiene que volver a cogerlo para que no se escape, aunque nunca había hecho nada por el estilo. Pero enseguida se da cuenta de que Silas corre atrás hasta la mujer, ladrando. Piensa que la pobre mujer se asustará, ella no puede saber que es el mejor perro del mundo. Pero cuando Silas la alcanza empieza a saltar y lamerla, y ella también como que le acaricia así, algo sorprendida, pero con bastante mano. »Elena e Isma enseguida llegan al rescate, Isma intentando quitarle el perro de encima, y la mujer pretendiendo explicarlo diciendo «será porque huele mi perra» y se ríe nerviosa. —¡Nooo way! —dice la amiga que todo este rato ha estado escuchando con la boca abierta—. ¡Qué fuerte! Me he quedado con una duda puramente logística y he parado de escribir. Miro a la narradora que, por si acaso no se hubiera entendido el significado de la escena, remata explicándolo todo: —¿Cómo lo ves? Te das cuenta de que tu marido te ha puesto los cuernos así en directo. Lo dice escandalizada, pero a la vez sonriendo orgullosa por la originalidad del asunto, y sin parecer sentirlo tampoco mucho por Elena, porque está ya recogiendo su bolsa y el jersey que cuelga sobre la silla. El camarero se ha dado cuenta de que se están levantando e imprime un papelito que deja sobre un plato de madera en la barra, y sigue haciendo cosas ficticias. —Pobre Elena —contesta la amiga, igual de superficial, mientras hace gesto de levantarse también—. ¿Entonces Isma ahora está con la otra mujer? Yo también tenía esa pregunta, pero por otro lado sigue habiendo algo que no me termina de encajar. Miro mis apuntes, pero tampoco quiero quedarme sin la respuesta sobre el final. Así que me levanto también acercándome a la barra tras ellas disimulando que justo iba a pagar. El camarero bizco, tan atento, lo ve y piensa que es verdad y empieza a imprimir. —¡Qué va! —contesta la narradora—. Al final esa historia no iba a ningún lado. Pero Elena ya tenía clarísimo que se quería divorciar, vamos. Lo tenía… pero clarísimo. Suelta una risa maliciosa. Pagan dejando el dinero sobre el platito. El camarero lo coge y me pone a mí el mío. La cartera está aún en mi bolso en la mesa. Llevo sólo la libreta y el bolígrafo. —Eso sí: él se quedó con Silas. ¿Cuándo te coges las vacas? —Perdonad —les interrumpo antes de que cambien de tema—. Sólo una duda. Se giran y me miran sorprendidas. Qué más me da. —Salen de la pescadería y desatan a Silas para irse. ¿Estaba atado delante de la tienda, comprendo? Las dos mujeres se miran de reojo y la narradora me contesta levantando los hombros y las cejas con gesto de que eso no tiene ninguna importancia y que no sabe a qué viene esa pregunta. Insisto: —Es sólo que no entiendo cómo ha entrado la mujer, quiero decir la amante, en la pescadería antes, sin que el perro la viera. ¡O sin ver ella el perro! Se podría haber dado cuenta del peligro y haberse dado la vuelta. La expresión de la mujer ha cambiado y parece que está ofendida. No sé si piensa que le estoy cuestionando la veracidad de la historia y por eso se pone tan a la defensiva. Pero antes de girarse enfadada y marcharse con su amiga me casi-escupe un “¡un poco de respeto por la privacidad de los demás!” El camarero se ha quedado como una estatua de sal al otro lado de la barra. ¿A que ahora no tiene ningún comentario fresco? Miro la cuenta que me había dejado. —Ahora lo pago. Vuelvo a mi mesa, aún me quedaba café. ¡Y ahora por fin tengo silencio! Claro, es que un detalle así yo lo necesito saber, no se puede dejar al azar. Luego el día del rodaje se encuentran con eso. Me como la galleta. Están ricas. Siempre es el mismo tipo, pero están buenas. Es un buen sitio, cuidan los detalles. Me obligo a volver a la escena de la piscina. Sólo tengo que romperlo, dar con la forma… Él la ve, sabe que es ella, pero no se acerca, y por eso nunca la vuelve a ver, porque… Aparece el camarero delante de mi mesa. Me mira fijamente a los ojos. Aquí no hay forma de que te dejen tranquila. —A mí me parece que Isma podría haber salido de esta, simplemente manteniendo la historia de que no la conocía. De que sería porque ella olía a perra. Me quedo sin saber qué decir. Y continúa: —O, ¿sabes? Podría haber reconocido que alguna vez se vieron en el parque porque ella tenía una perra con la que jugaba Silas. Y ya está. Pero de allí a revelar todo un adulterio… A este no hay quien le pare: —Me hubiera encantado oír el momento en el que aun así confesaba toda la historia. A ver, lo podía haber reconocido por cargo de conciencia, eso me parece bien. Pero la prueba del perro desde luego no sería válida en un juicio. Le miro con indulgencia. Es sabido que los camareros lo oyen todo. Pero tendrá que aprender que no debe revelarlo. Incluso el camarero confesor se caracteriza por escuchar, pero no opinar. Saco la cartera para pagarle.Third Prize Short Story in Spanish

La Iguana

Author: Fabian Vagnoni

Dual Degree in Business Administration and Data & Business Analytics

La Iguana

Al despertarse de su siesta, en pleno mediodía, Saulo notó que su teléfono había perdido la señal Wi-Fi. Agh, qué ladilla este celular, pensó mientras entraba en la configuración. Rápidamente, se percató de que no había ninguna red disponible. Antes de levantarse, se preguntó si el router se habría apagado. Se quitó la cobija de encima y puso los pies en el suelo helado. Ya era primavera, pero las baldosas de aquel apartamento siempre permanecían frías. Mirando la oscuridad a su alrededor, se cuestionó porqué levantarse de la cama. Mas, sin darse otra oportunidad para meditar, caminó hasta la sala y encontró la regleta sin corriente. Aja, se bajó el breaker, concluyó con certeza solo para encontrarse el breaker subido. Lo invadieron recuerdos repentinos del último apagón que vivió antes de emigrar. Supo que debía preguntar a los vecinos si ellos tenían luz, tal como se hacía allá para saber que el problema no era de uno cuando había apagones. Decidió arreglarse para salir a su encuentro con Erhard y ya, una vez fuera, preguntaría en la puerta de al lado. No quería perder mucho tiempo: si se había ido la electricidad, ya habría vuelto cuando él volviese en la tarde. Apenas atravesó el umbral de su puerta, vio las luces de emergencia encendidas. Supo que la luz se ausentó de todo el edificio, pero, para confirmar, intentó llamar al ascensor, fallidamente. Más tranquilo, sabiendo que era un problema común y esperando que alguien más le encontrase solución, bajó las escaleras cómodamente. Justo antes de salir, encontró al cartero esperando en la puerta. El timbre no servía, no podía pedir que lo dejasen pasar. Tras abrirle, y mientras el hombre caminaba apurado hacía las escaleras, Saulo le comentó que se había ido la luz en el edificio. El cartero respondió cortantemente: “Sí, en toda la zona”. Así que el barrio está sin luz, curioso, pensó Saulo saliendo. Solo fue cuando llegó al primer paso de peatones y vio los semaforos negros, apagados, y a los transeúntes incomodamente dudando en cómo cruzar, que entendió la magnitud del problema. Empezó a caminar apuradamente por la avenida. Erhard vivía cerca de la estación Colombia, podía llegarle por la línea nueve, pero tenía que andar hasta la estación más cercana, unos diez minutos. A cada paso que daba por la acera, oía más voces de desconcierto anunciando noticias tan inesperadas como imposibles. Palabras sueltas lo perseguían en su caminata, “Francia, Italia, Alemania, Holanda”, “Ciberataque”, “Los rusos”, “Acto de guerra”. Mientras Saulo casi trotaba con velocidad hacia el metro, su mente divagaba. Quizás debería intentar escribirle a Elena a ver cómo está, pensaba. El cartel del metro, con su llamativo rombo de listón rojo, se divisó a la distancia. Solo entonces Saulo entendió que, sin luz, no habría metro. Suerte era que la 147 pasaba cerca de casa de Erhard y tenía una parada justo allí, frente a esa estación de metro. Quizás sea un poco peligroso ir en carro ahorita, sin semáforos, pensaba Saulo, pero estaba dispuesto a correr el riesgo con tal de llegar a la 1:30PM, como se había acordado. Se montó en el autobús apenas este pasó. No tardaron en vivir paradas repentinas nacidas de malentendidos entre el conductor y los peatones sobre cuándo era el turno de cada quien. Sin embargo, Saulo pensaba que, aún con estas, siendo que faltaban todavía cincuenta minutos, llegaría a tiempo. Lamentable sorpresa fue cuando el conductor se hundió en el mar de carros que inundaban la Sinesio Delgado. Una calle normalmente poco transitada se había tornado en un charco de vehículos estancados. Tomaba unos minutos moverse un par de metros y, en la última parada, el autobús se había atragantado con tantas personas como la calle con carros. Con la asfixia del gentío y la desesperación del tráfico, Saulo empezó a impacientarse. Sabía que no llegaría a tiempo así, pero no estaba seguro de qué hacer. Súbitamente, una muchacha le pidió al conductor que abriese la puerta, a pesar de que faltaban aún más de cien metros para la próxima parada. Él, cediendo a las circunstancias, lo hizo y, en un segundo de impulsividad, Saulo saltó del autobús. Dándose la vuelta, su mirada encontró al denso bosque de personas que, por incapacidad para caminar o por esperanza de que la situación mejorase, se habían quedado en el autobús. Se sintió ofuscado por la imagen y se volteó para andar por la acera, sin mucha claridad en qué haría. De aquí a la torre son unos diez minutos, de allí a Plaza de Castilla son otros veinte, de allí a Cuzco son al menos otros veinte, y de Cuzco a Colombia son quince, estaré a una hora y algo de casa de Erhard, calculó rápidamente mientras se dignaba a caminar toda la distancia a paso apretado. Andando por la Sinesio Delgado, volteó hacia el Parque de la Ventilla y notó una afluencia tanto de gente como de perros. Quienes no tenían nada que hacer en casa parecían haber decidido entretener el rato con su mascota. Sin desconcentrarse, Saulo siguió andando hasta que, robándole la mirada, vio a unos chicos en un carro blanco bajando su ventana y haciéndole señas al conductor de al lado. El chico que iba de copiloto sacó el puño y lo movió, proponiéndole a su vecino conductor un juego de piedra, papel o tijera. Sacando papel, el chico perdió, todos rieron. Las almas en el hastío del Estigio, o de la Sinesio, parecen volverse más juguetonas, sonrió Saulo pedantemente. Justo antes de terminar la calle, volteó un momento y encontró, a la distancia, el autobús que lo llevaba. Se había vuelto un detalle perdido en la colorida pintura de la Sinesio Delgado y del Parque de la Ventilla, inundadas de carros, gente, perros. En diez minutos aún no había avanzado ni a dónde él había llegado en los primeros diez pasos. Llegó a Castellana. Pensó por un segundo en ir a la torre, mas supo que, sin luz, nada lo esperaría allí: no habría cómo entrar, ni cómo subir. Siguió, entonces, caminando solo con la idea de llegar a Cuzco lo antes posible. Pero, a medida que se aproximaba a las fronteras de Plaza de Castilla, la densidad de transeúntes iba encharcando la acera, ralentizando sus pasos. Una multitud, de mezclada confusión y risas, iba apoderándose de la calle. Protegido por las sombras de los árboles que dan a la avenida, el mar de individuos resaltaba con risas de jóvenes preguntándose qué hacer con su día, de treintañeros hablando de cómo volver a casa andando con zapatos de vestir, de señores celebrando el desconcierto en un bar con cerveza aún fría. Viendo las jarras frías y sintiendo el Sol inclemente posándose en su camisa oscura, Saulo añoró un vaso de agua. Pero, con solo diez euros en el bolsillo, pensó que no podía permitirse gastar dinero. Ahora que los datáfonos no servían, esos diez euros tenían que valerle para todo el día y, sin ellos, estaría desnudo. Habiendo llegado a Plaza de Castilla, se percató de que, sin teléfono para avisarle, Erhard no se daría cuenta cuando él llegase. Inmediatamente sacó su celular, entró en WhatsApp y le dejó un mensaje, con la esperanza de que, en algún momento, lo recibiese y algo se le ocurriese para darle la bienvenida. Pero, por encima de todo, apresuró el paso. Un leve presentimiento le susurraba a Saulo que, de tardar mucho, su amigo creería que no vendría y, una vez allí, no habría quien para recibirlo. Ni de vaina me voy a caminar esta pateada de vuelta vistiendo esta camisa y con esta pepa de Sol, pensó Saulo mientras sus pasos se deslizaban por la longitud de la avenida. Llegó a Cuzco sin percatarse, con la sorpresa de quien descubre que la infinidad de un kilómetro son apenas unos minutos caminando. Sin saber con certeza a dónde dirigirse, y siguiendo su afortunada intuición, giró hacia el Este por la Alberto de Alcocer. Cualquiera diría que Saulo llevaba toda su vida en aquella ciudad, aún cuando no la habitaba ni hacía un lustro. Siguió caminando, guiado por aquella orientación tácita, pero con la incertidumbre incesante de no saber dónde detenerse. Sé que es esta calle, pero no tengo ni idea de a qué altura era, Saulo pensaba mientras miraba paranoicamente a cada esquina, buscando una señal divina que le dijese “¡Era aquí!”. Sin encontrarla, seguía andando y su preocupación crecía. La avenida se inundaba de vehículos como el río estancado que se había formado en la Sinesio Delgado, todo mientras las aceras se anegaban con las mesas de bares, repletas de hastiados conciudadanos que decidían pasar su tarde de desconexión entre cañas y tapas. Ni con estas los de la hostelería podrán tomarse el día libre, pensaba Saulo mirando a los mesoneros migrar corriendo entre los destellos de la terraza y la oscura caverna del bar sin luz. Viendo que se le acababa la avenida, Saulo se detuvo en seco, sacó su celular y halló el vacío de sus chats y el incierto destino de mensajes sin enviar. Subió la mirada, desesperanzado. Una leve brisa le susurró que se tendría que devolver a su casa. Tan solo pensar en la media vuelta le corroyó un trozo de alma. Pero, interrumpiendo su pensamiento intrusivo, la figura de Erhard en un banco de la calle, sentado leyendo, lo liberó. -Hey, mano. -Hi.- Erhard sonrió con tranquilidad al verlo -¿Qué hacías aquí?- Saulo le preguntó, con ilusión en su voz -Esperando a que tú o Korina llegasen. No tiene sentido estar sentado en el apartamento, solo, sin luz. Saulo pasó junto a Erhard por el portal, que estaba en frente a dónde él se había detenido, de nuevo por fortuna de una orientación intuitiva. Al pasar, los saludó el portero con un estridente acento argentino. Subieron a pie los cinco pisos hasta el apartamento, casi cayéndose Saulo en los primeros escalones sin luz. Las linternas de sus celulares guiaron el resto de pasos. -¿Has comido? ¿Quieres un poco de queso cottage?- preguntó Erhard apenas Saulo había atravesado la puerta y empezaba a quitarse los zapatos -Em, no, no, no hace falta, comí antes de venir, gracias. -No te preocupes, te lo sirvo, si no se daña igual.- decía Erhard mientras habría la puerta de la nevera, sacaba dos botecitos de queso cottage y dos latas de CocaCola. Saulo no tuvo más opción que aceptar Sentados en la mesa de la sala, empezaron a hablar entre risas que rutinariamente se rompían para desvelar una creciente preocupación. Erhard le contó que Korina estaba en el metro y se quedó atrapada por al menos una hora, pero aún no tenía más información de ella. Saulo se sintió afortunado de haber salido más tarde de su casa de lo que tenía planeado. Por un instante, la señal volvió al teléfono de Saulo y éste, sin dudar, abrió el navegador y buscó las noticias. Encontró tranquilizadores titulares hablando de Portugal y España solamente, no de una caída en toda Europa. Pero, los reportajes eran escasos y disonantemente hablaban de la energía volviendo a ciertas partes del país, aún cuando en la ciudad reinaba su ausencia. -Lo más raro- decía Saulo- es que la red eléctrica no es un sistema que tenga un solo punto de fallo. No hay un solo cable que conecte todas las centrales hidroeléctricas, fotovoltaicas y caloríficas a la red… ¿Cómo puede caerse todo el sistema así? -Sí… ¿Sabes? Hay una ley que narra “Si algo existe desde hace tiempo, seguramente exista mañana”, el efecto Lindy se llama. -¿Qué quieres decir? -Piénsalo así: si un libro existió durante siglos, seguramente en diez años siga existiendo y… -Sí, sí, lo entiendo. Pero, ¿qué quieres decir ahorita?- Saulo interrumpió -Que esto va pa’ largo.- Erhard concluyó sonriendo tranquilamente- Tu sabes de sistemas. Cuando construyes un sistema y algo falla tienes dos o tres cosas que sabes que pueden haberse roto. Probar las tres te toma una, dos horas quizás. Luego, si no se resuelve, ya no sabes qué puede ser. En esas estamos. Seguramente los responsables no saben ya qué probar.- Saulo estaba atónito con el oximorón de la calmada desesperación confesada en las palabras de Erhard -Ay, Dios, es todo por la maldita iguana…- Erhard lo vio extrañado, Saulo se reía entre la nervios- Allá, cuando pasó esta vaina y se fue la luz por tipo una semana, dijeron que una iguana había jodido los cables. Repentinamente, se abrió la puerta. Korina entró, jadeando. Erhard se rió de ella, con ligera crueldad, mientras le decía que tenía que mejorar su cardio. Ella se rió sarcásticamente, saludó a Saulo, y se sirvió un vaso de agua. -No puede ser que esto esté pasando, estamos en una de las capitales de Europa.- La voz de Korina, aunque firme, revelaba la ansiedad que había aflorado en ella- Agh, siento que estoy todavía al borde de un ataque de pánico. Estábamos en el metro, la línea seis, que de por sí no me gusta, y se detuvo todo. El vagón frenó en seco, las luces se apagaron, si pasaba medio segundo más, hubiese empezado a gritar. Al menos se encendieron las de emergencia. Pero, pasaba el tiempo y nadie nos decía nada. Solo las putas vocinas sonaban cada cinco minutos diciendo la imbecilidad de “Queridos viajeros, les informamos que el tren se ha detenido por una avería ajena a Metro”.- Korina imitaba la voz con burla y rabia- Llegó un momento en que me tuve que sentar en el piso. El aire era demasiado pesado y necesitaba un poco del aire más fresco que se acumula abajo. -¿Y cómo los sacaron?- Saulo preguntó, curioso y preocupado. No se podía imaginar a sí mismo en esa situación sin bordar la locura -Abrieron las puertas. -¿Pero no estaban en medio del trayecto? -Sí, tuvimos que caminar por las vías hasta la próxima estación.- Korina sacó su celular y mostró las fotos. Erhard las miró con ligero interés, Saulo las observaba asombrado -Bueno, Koko,- Erhard se dirigió a Korina- Saulo y yo habíamos pensado en bajar a tomar algo en el bar, ¿qué mejor manera de pasar el fin del mundo que con unas cervezas? Tras ver la inundación de carros que ocupaba la avenida, se sentaron en la primera terraza vacía que vieron, solamente después de preguntar si la cerveza aún estaba fría. Erhard y Korina pidieron una jarra cada uno, Saulo se limitó a una cerveza sin alcohol, a disgusto de sus amigos. Las palabras no faltaron por las siguientes dos horas, aunque interrumpidas por incómodas sirenas, de ambulancias, de bomberos, de policías. Los tres hablaban alegres, pero los aullidos de las luces azules despertaban esa duda tácita sobre cuál sería el límite de todo esto. Korina y Erhard le insistían a Saulo sobre una película apocalíptica que debía verse, luego saltaron a hablar sobre lo que necesitarían acumular en su búnker, sobre las causas del apagón, sobre lo qué ocurriría cuando llegase la noche. Korina insistió a Saulo sobre quedarse en el apartamento con ellos aquel día y sobre tomar un dinero en efectivo que le prestarían. Él no quería aceptar, aunque tampoco quería verse desnudo de dinero ni volver a casa caminando ni, mucho menos, pasar la noche en su apartamento, solo. Pensaba que, de tener que hacerlo, no dormiría por los saqueos. Sin conocer exactamente sus pensamientos, pero viendo la inquietud confesarse en sus ojos, Korina siguió insistiendo. En cierto momento, ella se levantó para ir al baño. Erhard se terminó su tercera caña y, viendo la mitad de jarra que le quedaba a su ausente novia, la intercambió por la suya. Tras el primer trago, le preguntó a Saulo por qué pensaba que habría tanta gente con maletas. Él, sin haberse fijado antes, miró alrededor y encontró al menos tres o cuatro transeúntes andando con voluminosas maletas de veintitrés kilos. Respondió que seguramente estarían intentando llegar al aeropuerto, o se les habrían cancelado los vuelos y no les quedarían noches en el hotel. Erhard, suspicaz y escéptico, contestó que no debía ser, que nunca había tantos turistas por allí. Añadió que, además, era obvio lo inútil de ir al aeropuerto, insistiendo que intentarlo era sencillamente estúpido. Korina, al volver, se quejó sobre su nueva jarra vacía. Erhard, dándole un último sorbo a su cerveza robada, le devolvió la caña y dijo que no había pasado nada. Un poco irritada, ella la aceptó de vuelta. Dentro del bar, Korina había preguntado por comida para almorzar. No tenían nada más que unas pocas tapas. Sin luz, no hay cocina, le dijeron. Además, la gente de dentro del bar parecía estar empezando a ponerse histérica, señaló. Su comentario enervó a Saulo, aunque Erhard apenas reaccionó hasta que ella añadió que la cerveza se les había empezado a calentar. Se disponían a marcharse decepcionados, a regresar a las trincheras del apartamento, cuando Saulo notó, escabulléndosele por el rabillo del ojo, a un señor con una barra de pan de molde y una bolsa de supermercado llena. Lo comentó y Erhard no tardó en concluir que debía ser el hipermercado de arriba, que quizás siguiese abierto. Habiendo perdido su última oportunidad para disfrutar de cerveza fría, pagaron con efectivo una cuenta hecha a mano y calculadora, y salieron hacía el hipermercado. Saulo apretó el paso, intentando apurar a sus acompañantes. Él, tan pequeño, y sus amigos, cada uno sacándole al menos cabeza y media, se confundían por una pareja de padres andando junto a su hijo, impaciente e irritante, intentando presionarlos para caminar más rápido. Saulo no podía evitar sentirse así cuando los veía, torciendo el cuello hacia arriba, y percibiéndolos tan más preparados para la vida. Pero, ahora, lo único que le importaba era arribar al hipermercado antes de que potencialmente lo cerrasen. Cuando entraron por las puertas no esperaban ver, por primera vez en horas, luz eléctrica. Saulo señaló que tendrían un generador, pero que dudaba que los datafonos funcionasen. Y, a pesar de su duda, sí lo hacían. Se contentó al saber que podría pagar sus propias compras sin depender del dinero prestado. Pasaron a buscar lo que creían necesario. Lo primero, y esencial, fue ir a la sección de vinos, donde Erhard insistió en aprovechar la oferta de dos botellas por el precio de una para acumular cuatro en total. Saulo, en cambio, no tomó nada. Siguieron hacia la sección de embutidos, donde Erhard halló la frustración de los ausentes fuets. Se los habían llevado todos, pero buscó alguna otra carne que llevarse. Saulo, en cambio, no tomó nada. Mientras tanto, Korina investigó la sección de verduras, tomando todo lo que creía iban a necesitar por un par de días: pimentones, cebollas, pepinos. Saulo, en cambio, no tomó nada. Mientras andaba hacia el hipermercado, Saulo sufría la necesidad de acumular la comida que lo sustentaría durante estos días. Mas, al llegar, no era capaz de pensar en algo que realmente necesitase. Sufría ahora la incertidumbre de alacenas repletas, un impulso de aprovisionar, y nada que sintiese necesario. Únicamente podía traer a su mente la imagen de una barra de pan. Cuando Erhard le preguntó qué quería, como un padre a un hijo, él contestó que iría por el pan, singular pensamiento en su mente. Fueron juntos, cada uno a buscar el suyo. Y, frente a las tantas opciones, Saulo decidió tomar dos barras de pan de molde, una de semillas y una de centeno. -Aja, Erhard, ¿conseguiste tu pan?- Saulo preguntó una vez él tenía sus dos barras entre brazos, como dos bebés, hijos de su mente impulsiva materializada -No, mira, ¡todas las barras volaron!- Erhard apuntaba a la sección de panadería fresca, donde no quedaba más que el recuerdo de panes y panecillos -No, vale, pero Erhard, tú no quieres ese pan, esa vaina está dura pa' mañana. ¡Tú necesitas es la vaina más ultra procesada posible!- Saulo se burlaba, disipando su previo malestar -Fuck off! Cargando las cosas entre los tres, volvieron al apartamento. Mientras Korina y Erhard organizaban el mercado en la nevera, Saulo se había sentado en la mesa de la sala, pensando. Korina dijo que tenían que empezar a aprovisionar agua, pues en cualquier momento dejaría de fluir por las tuberías. Saulo recordó lo qué solían hacer antes de migrar: llenar tobos y bañeras con agua apenas se iba la luz. Aquí, sin embargo, no había esos utensilios. Así que, al final, propuso una ley a cumplirse bajó la jurisdicción de las cuatro paredes de aquel apartamento: todo recipiente que pueda llenarse con agua, se llenará con agua. Erhard puso sobre la mesa todos los vasos, uno a uno, y los llenó con agua de la jarra. Saulo sacó las ollas e hizo lo mismo. Hasta los floreros vacíos habían hallado una nueva utilidad. Y, cada vez que alguien tomaba un sorbo de agua de su vaso, Erhard corría a rellenarlo. Korina se percató repentinamente de que se habían olvidado de algo esencial: las velas. Dijo sentirse decepcionada de sí misma, tantos años oyendo a sus papás hablar de cómo gestionar estas crisis y ella viene a olvidarse de lo primero y más esencial. Erhard y Saulo salieron de nuevo, buscando unos chinos. Al andar, iban conversando y oyendo a la gente de la calle conversar. Saulo le hacía el favor a su amigo de traducir. No eran pocas las afirmaciones de que esto se extendería varios días. Saulo, bromeando, dijo que quizás deberían buscar un carro e irse hasta Francia. Pero, al mirar alrededor, encontraban también niños jugando en la calle, parejas paseando, gente caminando tranquilamente junto a su perro. Una situación desconcertante había sembrado tal impotencia en la mayoría que, sencillamente, los había empujado a buscar un día más tranquilo. Saulo padecía la disonancia de un mundo inundado de calma y manchado de incertidumbre. Al llegar a los chinos, las manchas se acentuaron. Había una fila de diez personas esperando fuera de la tienda, que se veía como un agujero sin luz, con puertas automáticas cerradas y una guardiana escondida entre las sombras. La dueña de la tienda abría, con el palo de una escoba, las puertas automáticas y preguntaba al siguiente en la fila aquello que deseaba, como un vendedor ocultista. Si lo tenían, te dejaban pasar; si no, te marchabas. Por suerte para Saulo y Erhard, aún restaban unas pocas velas en el bazar. Al volver, Erhard insistió en abrir la botella de vino. Korina hizo caso mientras comentaba: -¡Lo único que me preocupa es que es el fin del mundo y Saulo está sobrio! Poca opción le quedó a Saulo ante estas palabras. Sirvieron una copa a cada uno y brindaron: ¡Por pasar juntos el fin del mundo! Reían. Korina dijo, de repente, que había solucionado el misterio de las maletas: viendo por el balcón se fijó que alguien abría una y estaba repleta de comida. La fachada calmada de los transeúntes escondía una sospecha de que esto duraría días y que empeoraría rápidamente. Con las copas de vino en mano, a la luz de las velas, Korina sacó un cuaderno y un bolígrafo. Dijo que había que apuntar todo lo que necesitarían para montar su búnker, ahora, antes de que se les olvidará. Empezaron: un generador, comida enlatada, mucho combustible. ¿Cuánto? Saulo decía que debían tener un segundo búnker, del tamaño del primero, completamente inundado de combustible. Korina discutió que era demasiado, pero Erhard se posicionó con su amigo: la disputa se había resuelto democráticamente. Siguieron: muchísima agua, una mesa de pool y juegos de mesa, una computadora con juegos instalados en local, una consola, libros, velas. ¿Por qué velas? Korina dijo que las necesitarían, pero Erhard argumentó que con el generador bastaba. Saulo, en vez de tomar la decisión final, cambió de objeto diciendo que necesitarían armas. Korina apuntó. Con el juego, la noche había empezado a caer. Finalmente, el tema que Saulo había evadido a propósito se hizo evidente. Korina, sin proponérselo, mandó a Saulo a quedarse con ellos, cómo una madre a su hijo. Él, poco encantado con irse ahora, aceptó avergonzado y su vergüenza sólo creció cuando ella tomó del cuarto una camiseta y un pantalón de pijama de Erhard para que él pudiese dormir. Salieron todos al balcón a ver la noche. En las aceras solo existían luces fantasmales desplazándose con velocidad. Los edificios se observaban como siluetas agigantadas en la oscuridad oceánica que empapaba cada rincón de la ciudad. Cada silueta tenía pequeños y numerosos ojos amarillentos que confesaban una vela. La voz de la ciudad era de sirenas y silencio. Con decepcionante nostalgia, Saulo miró al cielo con la frustrada esperanza de encontrar estrellas. Ni la falta de luces las traía de vuelta. Mas, viendo hacia el final de la avenida, notó que el hotel que allí se hallaba tenía las luces de su cartel encendidas. Qué mala publicidad, pensó, toda la ciudad hundida en la penuria y ellos tienen la energía justa para hostigarnos con su publicidad. Pero, antes de que Saulo pudiese gesticular este pensamiento, la luz de cuatro farolas en la acera se encendió. Un eterno segundo de sorpresivo silencio siguió y, antes de la reacción de todos, mitad de los apartamentos se iluminaron. Gritos resonaban por toda la avenida. Saulo volteó a mirar a Korina, ella sonreía. Se oyó, a la distancia, un grito: “¡Viva España!”. Saulo gritó: “¡Viva España!”. Korina, riendo y con su acento extranjero, lo siguió. Erhard sonreía. La jornada se terminaba. En mitad de la madrugada, Saulo se despertó en una de sus vigilias rutinarias. Vistiendo la ropa de Erhard, miró el cuarto ajeno a su alrededor. Sabía que había soñado, pero no recordaba nada. Solo alcanzó a recordar que, en alguno de sus sueños, apareció una iguana.First Prize Short Story in English

Recordar

Author: Beatriz Sánchez del Río

Dual Degree in Laws and International Relations

Recordar

To remember is recordar. It comes from the Latin prefix “re”, which stands for the action of repeating something, and the noun “cor”, which means heart. To remember, in Spanish, is to go back to your heart. Susana thinks that to remember is to go back to your nose: nothing smells as good in English as it does in Spanish. That’s something she learned working in London, where she was forced to learn how to boil water for pasta. That was part of the process of realizing she had grown into an adult, a path that started some months before leaving Valladolid. She was enjoying the feeling of spending her first holidays with a paycheck, until the Christmas morning. She got a pot from Papá Noel. Her grandpa, who was as good as boiling pasta water as Susana, smiled to her as she unwrapped it. It was a durable as a tank. It likewise disturbed Susana’s peace. It was an unmistakable rite of passage into (boring, mundane) adulthood. He never had to learn how to make a tortilla. For fifty years, he had freely and delightfully enjoyed beefy cocidos and sweet arroces con leche. For fifty years, he had completely ignored the complexity of the vegetables market and its astonishingly high prices. For fifty years, he had been a husband. After fifty years, he had become a man again. He learned that bananas always spoil too quickly and that buying pans was as necessary as getting new pants—the lack of either of them can make you be nothing but skin and bones. So, he gave Susana the pot. Susana decided that she shouldn’t cry in front of her little cousins (they wouldn’t understand how tragic it is to receive household goods as a gift), so she said gracias. It was the same voice she could smell in the melted sweets that old ladies used to give her on the way out of church. Dirty and warm, hidden in patched pockets, like lies. Sugar- coated. The morning after, Susana complained to her mom about the present. It was big and heavy, so she couldn’t even take it with her on the plane. Half her luggage was already filled with vacuum-packed jamón. What was she supposed to do? She just couldn’t abandon her laptop, her most professional-looking boots and her warmest coat. She knew she wouldn’t cook in the United Kingdom. She wasn’t even cooking in her own country, where, at least, she could understand the ingredients of the labels at the supermarket. Her mom told her that there were some presents too heavy to take them with her. Susana should leave the pot. She and her father could use it while she was gone. Parents keep the heavy stuff while children fly away, at the end of the day. London smelled of burnt heating and, most days, of rain. Valladolid had a totally different scent: oftentimes, it simply consisted of coal. That was the winter smell of working neighborhoods, like Susana’s. She quickly realized how hard it was to close her eyes and pretend she was in Spain. It was too humid and too lonely, and it ended up stinking of tears. January ended with an aroma of menthol tissues, which she ran out of in the first weeks. Mom called her in February to tell her that grandpa was ill. In March, she was buying plane tickets when the phone rang. Madrid welcomed her with the odor of the chorizo sandwiches that tourists never seemed to get tired of, and a one-hour train to a funeral. She could only smell the food, not the train. Not even the funeral. He was a good man. Old-fashioned? Probably. He used to lower the blind every time he helped her grandma cook or clean. He was terrified of neighbors knowing he did chores as if he were a woman. Susana’s mom told her that he stopped being so ashamed when Franco died, but the truth is that no one ever saw him with a mop. It was an okay funeral. It would have been weird if it had been better. Fine things cannot happen on sad days. After mass, Susana went home with her family. Her parents had filled her room with old clothes and cardboard boxes. It all stank of the technology class she failed when she was thirteen because she didn’t know how to build a robot with recycled materials. Her grandma told her that the teacher was a gilipollas for failing her and made her a nocilla sandwich. Susana took the clothes off her bed and kicked the boxes. One was heavier than the rest. She looked at it, without bending (as one does when the world is tired). It was the pot. It didn’t shine; she could notice that it wasn’t new. Yet, it was clean. She hadn’t realized at Christmas, amid her soon-to-be—unfortunately, sooner-than-expected—midlife crisis… She opened the box. She smelled the pot. She remembered. Certainly, her parents hadn’t had enough heart to use it while she was gone. Sunday mornings, with grandma in the kitchen, scented her room. Back to the heart, in Spanish. Or was it the nose?Second Prize Short Story in English

The Echos We Keep

Author: Lara Geermann

Bachelor in Behavior and Social Sciences

The Echoes We Keep

The Automatic Door They met on my threshold. He stepped forward, she stepped back. We stayed open too long, confused. That’s how it started: hesitation. It was raining. He held an umbrella with one hand and adjusted a tote bag with the other, waiting for her to take the lead. She looked up, blinked twice, then walked in, nodding a thank-you she wasn’t sure he caught. They moved through the aisles separately at first – him in Produce, her in Dairy – but collided near the canned goods. Something about pasta sauce. They laughed awkwardly. She pointed at a brand she liked. He made a joke about dating advice from a tomato tin. I watched a spark flicker in the static of the store lights. Some doors stay open just long enough for a story to begin. The Woman at the Next Table He made the same joke twice. She laughed both times, too brightly – the way you do when you’re still trying to impress someone. She changed her order three times. He pretended not to notice. My husband and I watched them between spoons of our soup. "They remind me of us, all those years ago," I told him later when they left – still smiling, walking too close without touching. "We never did that dance," he said. "We just fell in." But I think we did. We just forgot the steps. The way she tucked her hair behind her ear. The way he asked too many questions about the wine. You could see them diving into each other, unsure but hopeful. We toasted to their beginnings with the last sips of ours. The Coffee Cup He always held me with both hands, even when I wasn’t too hot. Nerves, I suppose. She once doodled a heart on me with a pen. He never saw it. But I did. They came every Saturday morning. She’d talk about dreams – opening a bookstore, learning to ride, moving to Lisbon. He’d smile and nod and say things like "Someday," but his eyes were on her, not the future. Or maybe it was the same thing to him. And when she laughed – deeply, unapologetically – he’d glance around like he wanted the world to know it was him who made it happen. It seems that even the steam rising from me curled upward softer on those days. Like it knew it was part of something unfolding, something delicate and quietly extraordinary. The Barista They always ordered the same drink. Except for when she was mad. Then it was tea. You don’t switch from cappuccino to chamomile unless something’s up. He’d try to make her laugh. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes she’d stare out the window while he tapped at his phone. Sometimes they just sat, eyes meeting, like the moment was whole without words. I saw them through the seasons – scarves, sunglasses, puffer jackets. The city changed around them, but they were always here, in the same corner, on the same seats, like something solid in a world that kept on moving. One time, she left behind a napkin she’d been scribbling on – little hearts and a half-finished poem. He folded it carefully into his wallet when he thought no one was watching. Love lived in the quiet moments with them. The rhythm of their visits, the weight of their silence, the way their hands always found each other eventually – it was all part of the ritual. The Park Bench They sat on me every Thursday at noon. She read poetry. She liked the kind that didn’t rhyme, the kind that wandered, that left you a little lost before you found the meaning. She once said poems were like people – the good ones didn’t explain themselves right away. He’d lean back, eyes closed, listening like her voice was the only thing anchoring him to the world. Sometimes she’d stop mid-stanza and ask, “Are you even listening?” He’d nod without opening his eyes and recite the last line back to her perfectly. She smiled when he did that – not surprised, but pleased, like he’d passed a test he didn’t know he was taking. He always listened – but never read. Until last week. That’s when he brought his own book. Love, I think, is when you try. The Street Musician She danced once. Right there on the corner. Bare fingers, green coat, boots scuffed at the toes. My music in the air, in her ears, in her veins. He just stared, stunned quiet, like she’d turned gravity off for a second. I kept playing – some moments don’t need a spotlight, just a soundtrack. He pulled her close after she spun, as if holding her made the moment last longer. They laughed then – not because it was funny, but because joy like that has to escape somewhere. I’ve played for hundreds of couples. Most walk by. Some stop. Even fewer drop coins. But them? They let my music hold them for a while. You don’t get many of those. But when you do, it’s enough to keep you going. The Elderly Cashier He bought pasta. She bought canned tomatoes. But they placed everything into the same cart. I scanned their lives separately, but saw something shared. They had that soft, settled look couples get when they have learned each other’s rhythms – not bored, not rushed. Just comfortable. Matching shopping bags, grocery list debates, one cart between them. She asked if they had onions at home. He said probably. She bought them anyway. He teased her for forgetting the eggs. She rolled her eyes like she had done it a thousand times, but there was affection in it. They bickered at checkout over paper or plastic. Then he kissed her forehead while bagging the bread. She pretended to be annoyed, swatted at him with a receipt. But I saw her smile as they left – small, sideways, and entirely unmissable. The Engagement Ring Box He opened me with a shaking hand. She said yes before he could even ask. They laughed. I don’t know what they were laughing at, but it sounded like relief. I’d been waiting in a drawer for weeks. He’d taken me out late at night, opened and closed me like a question he couldn’t quite phrase. He rehearsed in mirrors, rewrote in his head, panicked more times than he’d ever admit. He almost brought me once, then didn’t. Another time, he forgot me entirely. But when it happened, it was simple – a park, golden light, a bench they sat on many times before. No speech. No spotlight. Just memories. Some yeses feel like fireworks. But theirs felt like two people finding breath after holding it too long. The Candle on Their Table My flame flickered more when they were quiet. Sometimes quiet is comfortable. And sometimes, it isn't. With them, it felt like both – like silence had become part of the furniture. There was wine, but no toasts. Food, but no laughter. He asked about work while pouring the second glass. She shrugged. She asked about his mother. He winced, then said something too carefully measured to be honest. She nodded like it was enough. Still, they passed the salt. Still, she refilled his glass before her own. Still, they held hands as they left – fingers intertwined like muscle memory. Like a promise you don’t say out loud anymore but still find yourself keeping. I burned until the end of the night. I always do. Even when the warmth I give is the only warmth left in the room. The Uber Driver I drove him after what must’ve been a fight. He said nothing when he got in – just nodded once and sank into the back seat, shoulders stiff, eyes unfocused. Still, he was clutching a wilted flower like it still had a chance. I didn’t ask. You learn not to. He just stared out the window with his jaw clenched and lips pressed together – lost in the silence of an argument still echoing, long after the shouting stops. We hit a red light. He looked at the flower. Turned it over in his hands. When we stopped, he didn’t get out right away, just stared at the entrance. Then he sighed. Not a tired sigh, not even a sad one. It was the kind of sigh that sounds like letting go of a hope you haven’t dared name out loud. He left the flower on the seat. No glance back. Just the quiet click of the door. I kept it there for a week. It didn’t rot or fall apart. It just dried up slowly, like something that had loved the light but knew it would never be touched by it again. The Street Lamp Outside Their Apartment He kissed her once under my light. She didn’t lean in. She didn’t pull away either. Some kisses simply don’t have answers. That’s how it ended: hesitation. They stood there too long. Not talking. Not touching. Just existing – together and apart, all at once. He shifted slightly, as if he might try again. She crossed her arms. He said her name. She didn’t answer. Then he nodded – like he understood something she hadn’t said – and turned. When he left, she stayed. Leaned back against the brick wall, arms wrapped around herself – not cold, just bracing. She looked up at me. I flickered. Not on purpose. But she smiled – barely. Like I’d said something kind. Or maybe just because someone, even if only an old streetlamp, had seen them try. The Park Bench She came alone this time. No book. No poetry. Just sat with her hands in her lap and cried. Not the loud kind. The kind that slips out in silence, when you’ve finally made the choice and now have to live with it. I felt the weight of everything unsaid settle into my wood. Not regret, exactly – just sorrow that something once so full could end so quietly. A jogger passed. A dog barked in the distance. The world moved on. But she didn’t. Just stared ahead like she was waiting for something to leave her body – guilt, maybe. Or the echo of the pain in his eyes when she had spoken those final words. And I held her, the only way a bench can. The Barista He’s still drinking cappuccino, but now in the mornings. She comes in the afternoons – chamomile, always. They never overlap. But they still sit in the same corner. Same table. Same seats. Like a habit neither of them wants to break entirely. And yet – there had been that one time. He was leaving just as she walked in. Neither expected it. They froze on the threshold of the door for half a breath, then kept moving – a quiet choreography of two people stepping around what used to be. No words. No smile. But their shoulders almost brushed. And neither looked back. They don’t ask about each other. Don’t mention the past. But I can tell – they still measure time by each other’s absence. The Remnants Love leaves echoes. Not just in hearts, but in corners of cafés, in the grain of old wood, in the flicker of a light that once saw a kiss. The world remembers, even when the lovers forget. From spark to stillness. From first hesitation to last. And maybe that’s why we’re here – the baristas, the benches, the musicians, the candles – to hold the shape of other people’s stories, long after they’ve let them go.Third Prize Short Story in English

The Country I carry

Author: Camila Cuetos

Bachelor in Communication and Digital Media

As the plane took off it finally dawned on me that I was departing to a country that had ceased to exist. It was a journey to the past of sorts, a place firmly frozen in time. Exactly as I left it at thirteen. Less than a day had passed since I received the dreaded call that a family member had passed away in Caracas, summoning me back to the country I had never properly bid farewell, but had since accepted as lost. Home had always been a tangible, physical space I’d revisit. As inevitable as the changing seasons so was my yearly return to Venezuela from Brazil, where I lived most of the year. My homecoming trip was a constant, a guarantee, and not once did I foresee any change to this routine. I’d only spend one month of the year at my grandparent’s home, but I looked forward to those thirty days with eager anticipation. I feel as though my childhood exists as a series of blurred, unreliable memories, with the exception of those clear, animated recollections of my time in Caracas. Those stand out among the haze of the past and seem with time to gain heightened detail, like an old song whose lyrics finally reveal themselves with lived experience. In the summer of 2013, at just thirteen, I unknowingly took my last plane home. Even now as I recount my final days in Caracas I carry a deep, persistent remorse for taking for granted what I now miss most. Like most teenagers, I threw my days away online and was too hooked on digital screens to notice my crumbling, dissipating surroundings that would eventually vanish, like a perplexing dream once you wake up. To this day my memories are fractured and broken up. There were details I had not consciously tried to preserve and I find myself agonizing over these elements in my memories. Did my grandparent’s dining table seat 6 or 8? Was there really a window at the end of the hall? I cannot help but feel a bizarre frustration, as though that version of myself was selfishly denying me of more fragments and traces of my home. Though I know I should not have expected more of myself at that age; I was a young girl, oblivious to what lay ahead. At the country club my family went to, I became acutely aware of my status as an outsider. The other children weren’t just regulars of the club, they were locals who belonged to the city. And I was a mere visitor, my time there always temporary and fleeting. Conversations with them were sprinkled with slang I did not understand and mentions of unfamiliar places I did not know. These passing interactions, though brief and rare, accentuated the gulf between us and I realized then, perhaps for the first time, I was truly a foreigner in my own homeland. As the days drifted by, I watched the local children with mounting envy, realizing they inhabited a version of my country I had not had the privilege to experience myself. I craved their lifestyle intensely, fantasizing about what my life would be like in their shoes. One night as my parents and I sat in silence, trapped in traffic, I suddenly asked what school I’d attend if we ever moved back. My mother paused and for a moment there was a soft suspense lingering in the air, hinting at a well thought-out answer. Finally, she did and the mere existence of an answer brought deep comfort to my heart, as though my future life in Caracas was on the horizon and set in motion. That last visit was undoubtedly the summer of revelations, as I began to notice around me things I had long ignored. I guess part of this comes with age. At thirteen, childhood innocence seems to slowly shed away and suddenly so much about the world crystallizes into more clarity. Among the highways of the city, political campaign posters hung up in the sky, lingering for months after the election and watching the people below. Grown ups moved with heightened alarm, their slight anxiety noticeable when getting in cars or walking around, perpetually vigilant to the threat of robberies, or worse. It became exceedingly clear to me that I was in a fractured country, and though I lacked the precise knowledge to understand the economic and political deterioration, I could feel the suffocating weariness that hung in the air. Stories of kidnappings were not uncommon at dinner tables. Usually adults were cautious and shielded children from these morbid tales but with time I started reading between the lines and came to understand the realities that struck my country. At thirteen I stood at the precipice between childhood innocence and the brutal awakening of the turmoil that was transforming the nation I had once known. That summer of 2013 was the last time my family traveled to Venezuela. Looking back, the signs were there. It was a country on the brink of a nightmare and I witnessed some of its last days before the harrowing consequences truly settled. I am tapped on the shoulder by the flight attendant for the complimentary meal, momentarily anchoring me back to the present. Looking around the crowded plane, it’s hard not to imagine the stories and journeys each person carried. A myriad of different migration odysseys with a universal thread tying us all together. If you could measure the mixed emotions among us, like a heat map, I’m certain this plane would be a searing, bright red. For some this may just be a routine flight, but for many this feels like a pilgrimage of return of sorts. Not entirely though, since we are mostly just passing by. Suddenly I feel the tremendous weight of this return, the pressure pushing against me making me feel almost claustrophobic. An array of thoughts and questions emerge simultaneously, making me realize I’m not just heading home but to an unknown. The image of Venezuela I’ve preserved over the last decade or so, will now collide with the living reality, forcing my memories to surrender to what my country has since become. Yes, I’ve read the news and headlines, but to see it with my own two eyes would be to shatter my childhood illusions. How much of that idealized, beloved version of home will survive once I am confronted with the true state of affairs? How tainted will my rose-tinted memories become? I am afraid to confront the beloved illusion of home that I built as a child. I don’t want to face the place I adored with innocent eyes now that I’ve grown. Those fragments of my past give me comfort at night when I succumb to nostalgia. They remain my source of light when I am at the brink of despair. Even as cynicism takes hold, it’s the echo of those treasured memories that restores and nurtures my love for Venezuela. It gives me the courage to hope. As we near Caracas and fly over the vast atlantic blue I think of a song I heard all throughout my life with words that still resound very true: “entre tus playas quedó mi niñez”. Between your beaches my childhood was left…. I begin to wonder if it was a coincidence at all that I stopped visiting at exactly thirteen. Is this all a cruel joke, a fated metaphor of sorts to mark the definitive end of my childhood? Does my younger self still roam around the beaches of Margarita? Do her eyes still glisten with dreams of truly returning home? More than anything I wish she remains there on the shore. I need to hold onto that past for any future I can hope for. It is that version of home, of my country, that I carry.First Prize Short Essay in Spanish

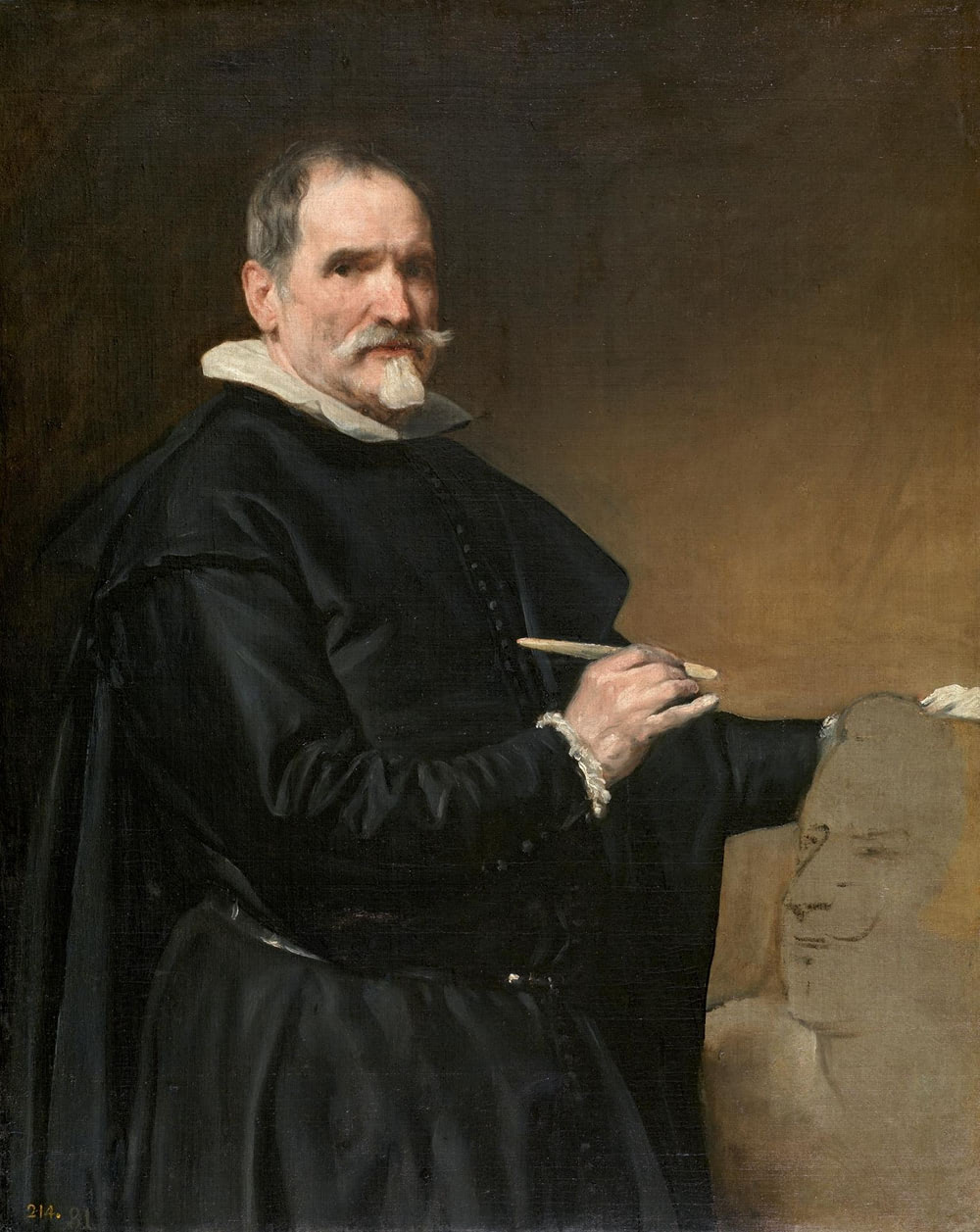

Velázquez y la construcción de la individualidad

Author: Victor Carmona Vara

Bachelor in International Relations

Velázquez y la construcción de la individualidad:

Sala 009A:

Cuando llega el fin de semana, el Prado se llena de turistas. Convertidas en una segunda Babilonia, algunas salas se ponen imposibles, sobre todo si fuera hace frío y llueve. La recepción se llena y terminan por mezclarse franceses con portugueses, japoneses con estadounidenses y locales con turistas llegados de donde da la vuelta el aire.

Hay otras salas, sin embargo, que están siempre tranquilas. Pienso en la zona de la colección dedicada a la escultura antigua, que tiene el mismo tránsito que una oficina de correos pasadas las dos de la tarde, en las capillas románicas, tan desatendidas, y en la pintura histórica del XIX, que no interesa mucho. Allí uno se siente muy a gusto, puede pasear a placer y no suele haber ruido. Curiosamente, algunas salas preñadas de cuadros de Tiziano, Murillo y Van Dyck no tienen mucho trajín aunque están pegando con el pasillo central: son como las plazas apacibles y provincianas que están junto a Avenida de América o Cristo Rey. Pero luego está la famosa galería central y las estancias aledañas, desde El Greco hasta Goya. Allí, no importa el día, siempre hay muchísimo tránsito y a veces se hace difícil ver algunas de las obras más conocidas. Junto a esta zona, como un muro de contención, hay algunas cámaras que son de descanso, con bancos en el centro. Se sienta todo el mundo: los adolescentes de la excursión del colegio miran el móvil y se ríen o guardan un silencio hormonal; los turistas mayores se echan en el respaldo, rezongan un poco, tosen y cierran los ojos; y los maratonianos japoneses se sientan muy rectos y ponen los pies en alto. Una de esas salas de descanso es la 009A, una estancia de decoración temática y desigual.

En la 009A se exponen todos los cuadros que colgaban en el Salón de Reinos del Palacio del Buen Retiro, la residencia real que le da nombre al parque más famoso de la ciudad. Construido en la época de Felipe IV, patrón, entre otros y sobre todo, de Velázquez, ahora sólo quedan dos edificios de lo que fue un inmenso conjunto relativamente olvidado: el Casón del Buen Retiro y el ya mencionado Salón de Reinos, en el que se reconocen de una forma mucho más evidente las formas del barroco madrileño. Por el Casón apenas pasan unos pocos informados que, el domingo a mediodía, interrumpen la placidez del estudio de los investigadores que manosean libros en la sala de lectura para echarle un vistazo a la bóveda de Luca Giordano. Por el Salón de Reinos, en puridad, y hasta que terminen unas obras que se eternizan, no pasa nadie. Pero hubo un tiempo en que en el Salón se desarrolló uno de los más complejos conjuntos alegóricos de reivindicación de la monarquía de los Austrias. Ese mismo conjunto es el que se puede ver, entre ronquidos disimulados y enormes bufidos de cansancio, en la sala 009A.

Hay que reconocer que la mayoría de lo que allí se expone es de lo menos apetitoso. Muchos autores de segunda y hasta de tercera fila firman cuadros decentes pero fríos como témpanos -Vicente Carducho, Jusepe Leonardo, Eugenio Cajés etc.- y conviven con el peor Zurbarán, que no sé en medio de qué ataque de apoplejía se puso a pintar la serie sobre los trabajos de Hércules. El conjunto, visto así, aturde un poco, sobre todo si ya se ha pasado por el muy demandante pasillo central. Sobreestimulado, es posible que al visitante cansado se le pase por alto un cuadro que, aunque reproducido cien veces, no pierde un ápice de su fuerza: “La rendición de Breda”, es decir “Las lanzas de Velázquez”, que es el título oficioso por el que le conoce todo el mundo.

“Las lanzas”, separadas del resto de la producción de Velázquez para reproducir el Salón de Reinos, valen por sí solas toda una mañana. Se han querido hacer muchas lecturas superficiales del cuadro, desde la reivindicación nacionalista al elogio de la técnica, entro los que hay que destacar algunos comentarios estilísticos sobre la creación de vacíos y nexos narrativos. Pero su valor primordial reside, a mi entender, en el gesto sobrecogedor entre Spinola y Justino de Nassau, el holandés derrotado que ve cómo el general italiano interrumpe su humillante genuflexión, representación máxima de la pretendida magnanimidad de la Monarquía española pero, sobre todo, ejercicio de una profunda humanidad, que es la marca de la casa de Velázquez desde el inicio de su producción. Los cuadros a nuestro alrededor nos dicen pocas cosas porque, por lo general, la propaganda envejece mal. Pero ante “Las lanzas”, independientemente de si se sabe o no qué fue la guerra de los Ochenta Años, si se comprende bien la escena o si se conoce a Velázquez, muchos visitantes inadvertidos terminan por emocionarse aunque sea un poco.

Miramos de nuevo al lienzo. A la izquierda, del lado de los holandeses, un joven con el arcabuz al hombro se fija en nosotros, como si nos hubiera sorprendido cotilleando, y tiene una expresión que oscila entre la sorpresa y el disgusto; a la derecha, tres soldados españoles nos examinan con calma. El que está más cerca de Spínola, con perilla, bigote y cara de libertino, nos contempla entre socarrón y condescendiente, como si nos hubiera pillado en falta. Tras él, un hombre mayor con barba cerrada nos mira triste, casi nos atraviesa con los ojos para dar en la pared de enfrente, perdido en no se sabe qué simas. El otro, al que sólo vemos de medio cuerpo y que casi se sale del cuadro, está melancólico y quisiera bajarse para hablar con nosotros, fuera ya de la guerra y de su tiempo. Parece, a juzgar por el extraordinario naturalismo de la escena, que estamos siendo testigos presenciales de algo que ocurrió tal y como lo estamos viendo; que el paisaje de Breda es así; que las mismas columnas de humo que pinta Velázquez debieron conectar el cielo nublado con el cansancio terrenal de la guerra. Y es así como pasan desapercibidos los extraordinarios trucos estilísticos del pintor, como la creciente abstracción de las caras, que muchas veces no pasan de una primera mancha colorista, o el brillante truco de perspectiva que permite que veamos, de forma completamente anti-intuitiva, toda la llanura holandesa. La escena principal, hecha de color y empastes, destaca sobre el fondo líquido y lleno de veladuras, más impresionista que preciosista, en el que lagos, incendios, ríos y ciudades se insinuan con formas tenues y pinceladas diluidas.

Miramos una vez más: las figuras centrales, Spínola y Nassau, exudan paz, profundidad de espíritu y caballerosidad. Entre ellos no existe el odio y los desastres de la guerra se difuminan a su espalda. Derrota y victoria son aceptadas con honestidad: son los últimos resquicios de una cultura caballeresca casi feudal que se difumina. La visión ennoblecedora de la guerra en Europa está a punto de perderse para siempre. Las guerras de religión de los Treinta Años introdujeron el factor del odio, acrecentado por las revoluciones, las contrarrevoluciones y la ideología, productos de la naciente sociedad contemporánea. Entre el “Carlos V en la batalla de Mühlberg” de Tiziano, muy en el espíritu de “Las lanzas”, y “Los desastres” y las pinturas del 2 y 3 de mayo de Goya, se produjo un cambio total de paradigma. La guerra cruenta y tecnificada que comienza a finales del siglo XVIII va a cambiar para siempre la visión que aún primaba en tiempos de Velázquez. Es por eso que Goya, Dix, Picasso, Anders o Sontag la miran con otros ojos. En ese sentido, como en los retratos de corte, Velázquez es el retratista de un mundo perdido, un puente entre nosotros y el Antiguo Régimen en España. Pero ese papel lo cumplen también otros pintores de su época, de Carreño de Miranda a Pantoja de la Cruz, y ellos no son Velázquez.