The Courage to Be a Beginner: How Embracing Discomfort Fuels Growth

By Dr. Silvia Centeno

Why being bad at something might be the smartest thing you can do for your brain and well-being

1. the productivity trap: why we avoid being beginners

We live in an age of efficiency. Productivity hacks, performance metrics, and the relentless pursuit of optimization dominate our personal and professional lives. In this environment, the idea of doing something you’re bad at seems counterproductive—why waste time struggling with something when you could focus on what you already are good at?

But here’s the paradox: our obsession with productivity may actually be holding us back from true growth and fulfillment. Research on cognitive flexibility suggests that when we only engage in tasks where we feel competent, we limit our ability to adapt, innovate, and expand our thinking (Diamond, 2013).

This year, I taught a course called Courage, Creativity, and Willpower . One of the key themes we talked about was the importance of having the courage to step outside our comfort zones—because that’s where growth happens. Yet, most of us don’t leave our comfort zones voluntarily. Instead, we wait until life forces us out—through a crisis, a job loss, a sudden change—before we finally embrace the unknown.

But what if we didn’t wait? What if we actively sought out challenges that scared us?

2. the neuroscience of being bad at something

Did you know that your brain loves a challenge?

When you struggle with something new, your brain strengthens its neural pathways through neuroplasticity—the process by which the brain rewires itself based on new experiences. Neuroscientific research shows that learning new skills, especially difficult ones, strengthens existing neural connections and creates new ones, making the brain more adaptable and resilient (Doidge, 2007).

Additionally, engaging in mentally demanding tasks—like learning a new language, playing an instrument, or even trying a new sport—helps protect against cognitive decline and improve executive function (Park & Bischof, 2013).

Struggling through a new skill also activates dopamine, the neurotransmitter responsible for motivation and reward. This means that, even if the learning process feels frustrating, your brain is chemically reinforcing the experience and preparing you to improve (Schultz, 2015).

So, while you might feel uncomfortable at first, embracing new challenges is literally making your brain stronger.

3. discomfort and growth: the role of fear, humor, and gratitude

Let’s be honest—being bad at something isn’t fun. It’s uncomfortable, awkward, and sometimes embarrassing. That’s why your mindset matters when facing challenges.

• Fear: A Signal That You’re About to Grow

In my Courage, Creativity, and Willpower course, I asked students to reflect on moments when they had to step into something that scared them—whether it was giving a speech, starting a new project, or taking on a leadership role. The common pattern? Every meaningful achievement in their lives had been preceded by discomfort.

Fear is often misinterpreted as a warning to stop. But in reality, it’s a sign that you’re about to expand your boundaries. Instead of avoiding fear, we should lean into it—because the things that scare us often hold the most potential for transformation.

• Humor: The Secret Weapon Against Fear of Failure

Laughing at your own mistakes can shift the emotional weight of failure. Studies show that humor reduces stress and increases resilience, helping us recover faster from setbacks (Martin, 2001). When you can laugh at yourself, you remove the stigma around failure and turn it into a learning experience.

Instead of thinking, “I’m terrible at this”, try saying, “Well, that was hilariously bad—let’s try again.”

• Gratitude: Reframing the Struggle

Instead of focusing on what you can’t do, try focusing on what you can. Neuroscientific research shows that practicing gratitude activates brain regions associated with motivation and long-term well-being (Fox et al., 2015). If you approach a new skill with a sense of appreciation—“I get to learn this” instead of “I have to”—you’re more likely to stick with it.

4. Why embracing incompetence can make you better at what you´re already good at

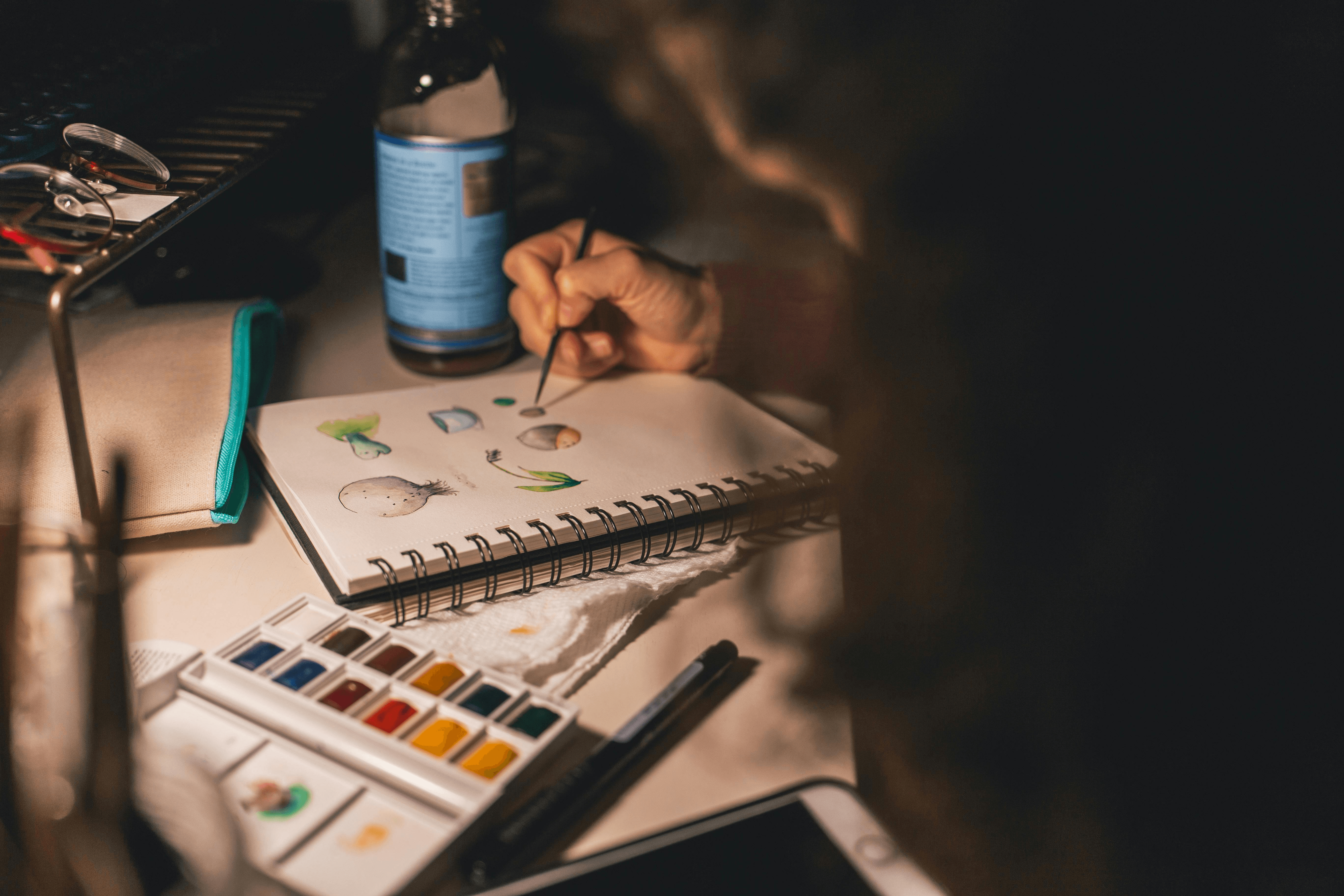

Stepping outside your comfort zone in one area often improves performance in another. A CEO who takes up painting might develop better problem-solving skills at work. A scientist who learns an instrument might discover new ways to think creatively.

This is because cognitive flexibility—the ability to shift between different ways of thinking—enhances innovation and adaptability (Diamond, 2013). Struggling with something unfamiliar strengthens your brain’s capacity to learn and adapt across different domains of life.

Challenging yourself in areas where you lack skill can make you even better at what you already do well.

5. the beginner´s mindset: a recipe for a fulfilling life

In Zen Buddhism, there’s a concept called Shoshin, or “beginner’s mind”—an attitude of openness, curiosity, and humility when approaching new experiences (Suzuki, 1970).

A beginner’s mindset doesn’t mean aiming for failure, but rather embracing the learning process without the pressure of immediate success. It means giving yourself permission to be bad at something, just for the sake of learning.

Think about it: when was the last time you allowed yourself to be truly bad at something?

Maybe it’s time to pick up that instrument you never learned, try a new language, or sign up for a dance class even if you have two left feet.

The courage to be a beginner isn’t just about learning new skills—it’s about adopting a mindset that leads to deeper growth, greater resilience, and a more fulfilling life.

References

• Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168.

• Doidge, N. (2007). The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science. Viking.

• Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

• Fox, G. R., Kaplan, J., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. (2015). Neural correlates of gratitude. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1491.

• Martin, R. A. (2001). Humor, laughter, and physical health: Methodological issues and research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 127(4), 504-519.

• Park, D. C., & Bischof, G. N. (2013). The aging mind: Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(1), 109-119.

• Schultz, W. (2015). Neuronal reward and decision signals: From theories to data. Physiological Reviews, 95(3), 853-951.

• Suzuki, S. (1970). Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. Shambhala Publication