Most of us understand that our current levels of stress and our diminished social connections are simply not healthy for us. We make an effort to fix this, seeking solutions and trying to cultivate good habits – but still, we procrastinate, have trouble with memory, sleep poorly, have digestive issues, and feel tension in our relationships. It can get quite frustrating.

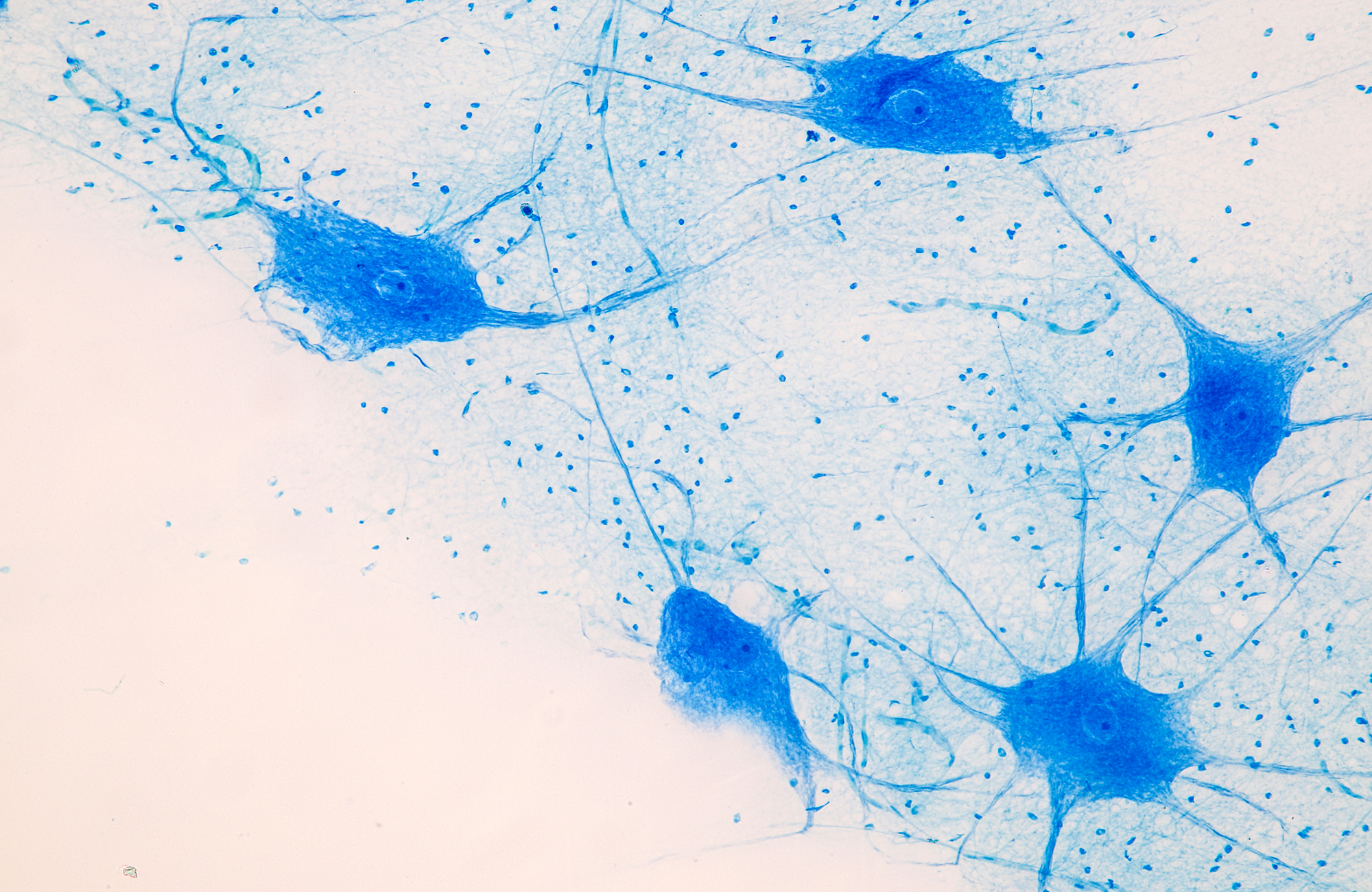

Why do wellbeing and modern health practices so often fail us? The answer is in our nervous system. The real differentiator in our wellbeing is our neurophysiological state, not our mind. When our nervous system does not feel safe, it is difficult for us to be collaborative and present, let alone mindful and meditative.

The good news is that we can befriend our nervous system and gain better control of our physiology and mind. For example, the Polyvagal Theory, also called the Science of Safety, developed by American psychologist and neuroscientist Dr. Stephen W. Porges, provides a tangible map for better stress management and increased wellbeing and performance. Polyvagal performance coach Michael Allison observes how athletes can train for peak performance, not by getting fitter but by enhancing their capacity to manage their bodily state: “Every single aspect of performance, from power, to endurance, to mechanics, to execution; even your creativity, problem solving, confidence, and belief – all are built on top of your bodily state.”

The Polyvagal Theory is based on three premises:

Neuroception: Our bodies respond to safety and threats detected from internal and external signs and from our relationships with others. The nervous system does not make moral meaning or assign motivation, nor does it differentiate between physical and psychological threat. It simply reacts to ensure survival. This survival mode can sometimes come across as laziness or aggression, but these apparent character flaws may actually be a triggered nervous system reaction. What commonly trips us up as individuals and gets in the way of well-intended company programs focused on psychological safety, DEI, and wellbeing, is that we focus on cognition and linguistics but our detection system is ancient. It operates the same way it did when we were scanning the horizon to ensure our physical survival.

Nervous System Hierarchy: There are three predictable responses to our perception of safety and danger: connected and safe (ventral vagal), alert and ready for fight or flight (symphatic), or paralyzed and shutdown (dorsal vagal). Based on our state, our biology supports or restricts sensations, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. These autonomic states shift in response to the everyday challenges of life. There is a time and place for fight, flight, and freeze reactions and the goal is not to be permanently Zen but to successfully navigate these shifts and be able to weather those that are truly challenging.

As Dr. Gabor Maté details in his book The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture a modern world that is competitive, disconnected, and critical, does not support a sense of safety, and such accumulated stress can also be traumatic for the body. Many of us live without conscious awareness of trauma but suffer the consequences. Emotional, physical, and psychological trauma can lead to distrust, hypervigilance, and arming oneself ‘just in case’. In other cases, trauma can have the opposite effect and cause us to ignore genuine warning signs.

Although there are many people in the world dealing with shock trauma that comes from experiencing natural disasters and war, the most common trauma in the industrialized world is early and developmental trauma that stems from a lack of secure attachment. This shows just how prevalent it is in our society today – and signs of such lingering trauma include severe procrastination, lack of drive, self-sabotage, difficulty setting boundaries, a tendency towards toxic relationships, and difficulty setting and achieving goals despite considerable effort made. Other signs include chronic health or weight issue even when practicing a typically healthy lifestyle.

A Need for Social Engagement: Humans are a social species. Our biology is wired to connect and regulate our nervous system states with that of others. Human interactions help us feel safe and guide us back to safety after a perceived danger – and our nervous systems actually seek out others with whom we can create these supportive and protective relationships. For example, when we send cues of danger or receive a warning from another person, our reactivity increases and our survival responses are reinforced. However, when living with trauma, our nervous system takes us into social isolation – the opposite of what it was built to do.

Have you ever been in a room and felt the atmosphere change due to another person’s presence? This happens because we read each other’s nervous systems, so someone who is in a state of hypervigilance – or someone in the calm, ventral vagal zone – can have an immediate impact on people around them. This is especially true in regard to the energy coming from those in a position of authority.

We must learn to ask ourselves: at this moment, here and now, with this person or with these people, is this level of response needed?

In the workplace, the key to genuine and sustained psychological safety rests in the team leader’s own inner sense of safety. When your director or boss emanates calm (because they genuinely feel it), your own nervous system relaxes. It’s thus essential to promote individual nervous system safety first in order to build psychologically safe teams and, ultimately, organizations. Compassion, curiosity, learning, clear thinking, and cooperation are possible only when we are in the ventral vagal zone, feeling safe.

On the individual level, the first step is to befriend our nervous system. We must learn to ask ourselves: at this moment, here and now, with this person or with these people, is this level of response needed? Where am I in my nervous system? You are simply gathering information. Observe without judgement or criticism, it is perfectly ok to feel disoriented.

Our brains are designed to change throughout life and every experience, sensation, and interaction changes the brain either towards the new or towards reinforcing pre-existing networks. According to Bessel van der Kolk, author of The Body Keeps Score: Mind, Brain, and Body in the Transformation of Trauma, there are three paths to brain change and while we often have our go-to favorite, it is usually best to combine the three approaches for faster and more sustainable change. Just as with physical exercise, short but consistent daily practice is better than an occasional marathon. The three pathways are:

- Bottom-up – through body: These techniques work through the body to change the brain, especially the areas of the brain outside of conscious awareness and control. They include various breathing techniques, progressive muscle relaxation, yoga, tai chi, qi gong, physical exercise, and some meditations.

- Top-down – through mind: The top-down techniques engage the brain through cognition. These techniques include for example reframing, talk therapy, mindset and habit change, research, mindfulness, and some meditations.

- Horizontal – through both hemispheres of the brain: Horizontal techniques work on both hemispheres of the brain. Art and other expressive forms therapies, music therapy, walking, drumming, and EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) are some examples of horizontal techniques. Nature, and in particular water, is a wonderful way to increase safety and we can even obtain the benefits by simply looking at images of nature.

We must learn to tune into our own nervous system and to also be curious about what is happening in another person’s nervous system. This knowledge can open up a universal language that is able to support us in a positive way for the rest of our lives. By working with our biology and enhancing our capacity to connect, we can use our minds, our body, and our energies to think and perform in a more powerful way because we are not in survival reaction mode. Safety increases our resilience, joy, strength, passion, and aliveness even in today’s competitive, uncertain, and challenging world. When we are in deeper contact with ourselves, we can be authentically present with others.

© IE Insights.