After returning to the office from maternity leave, many professional women find themselves carefully managing how they appear at work. They select clothes that conceal physical recovery and apply makeup to project energy despite weeks of fragmented sleep. None of this is formally required, yet it often feels essential to being seen as competent, committed, and professional. Long after maternity ends, mothers continue to navigate quiet but persistent pressure to ensure that the visible traces of caregiving remain outside the professional frame.

This tension helps explain why returning to work after maternity leave remains so difficult. Becoming a mother may be one of the most common transitions in adult life, yet the shift back into the workplace often feels anything but ordinary. Challenges such as sleep deprivation, fluctuating hormones, and ongoing breastfeeding are difficult enough on their own – without also having to navigate workplace expectations and unspoken norms that infer these realities should be checked at the door.

Given that mothers make up a substantial share of the workforce, this mismatch shouldn’t exist. Yet progress in formal equality has outpaced the everyday norms, expectations, and structures of many workplaces, leaving new mothers to navigate systems that weren’t designed with them in mind. Rather than integrating motherhood into working life, many workplaces operate as if mothers should return as though nothing fundamental has changed. The implicit message is clear: while motherhood may be celebrated in society, in the workplace, it is expected to remain out of sight.

Research has documented how pregnancy is often seen as a “misfit” within organizational norms, associated with disruption, reduced commitment, or simply being out of place. Yet the tensions between maternal realities and workplace expectations do not end with pregnancy. After childbirth, mothers are left to reconcile two competing worlds: one that fully acknowledges the ongoing demands of caring for an infant, and another that expects them to perform as if those demands do not exist. In fact, there is a disparity, as Caroline Gatrell of the University of Liverpool details, between the experience of new mothers in the workplace and the equal opportunities policies designed to protect these women.

Together with my coauthors at Aalto University School of Business and Royal Holloway Business School, I examined how professional women manage visibility in the workplace after returning from maternity leave, and the expectations that shape these efforts. The women we interviewed described numerous aesthetic and material concerns in balancing motherhood and career – for example, meticulously selecting clothes that minimize changes to their bodies, applying “natural” makeup to appear refreshed, and blurring their backgrounds on video calls to hide the chaos of motherhood around them.

Our study identified distinct material practices through which women negotiate the boundaries between maternal identity and workplace norms. Creating the appearance of professionalism for women involves “bordering,” which means keeping the maternal body and domestic environment outside the professional frame. Women described changing into office clothes not only to look professional, but to erase the traces of caregiving from their sense of self. Many said that going to work without makeup would feel like being naked, as if their unfiltered appearance were inappropriate. One woman explained that once she returned home, she would “undress the work,” as though professionalism were a costume to be removed or a role to be performed.

Remote work does not always relieve the pressures these women face. While it is often portrayed as liberating for working parents, our study reveals a more complicated reality. The home becomes another space that mothers feel pressured to curate – angling their cameras to hide toys, laundry, or other signs of domestic life.

Expectations that women return to work and perform as if nothing has changed for them generate significant anxiety. A study by & Culture found that more than half of mothers report dissatisfaction with how they were treated upon returning to work, while 70 percent describe stress, anxiety, and even dread when preparing for their return. These patterns point to a broader organizational risk: the loss of valuable talent, the reinforcement of gender pay disparities, and a growing likelihood of parental burnout.

Beyond the pressure to conceal caregiving, our study also found that new mothers often feel pressure to “reclaim their pre-pregnancy body.” Clothes that once signalled confidence and competence instead become reminders of physical change, symbolizing a perceived failure to “bounce back.”

The physical recovery that follows childbirth has direct consequences for how mothers are able to work, yet these are rarely acknowledged in workplace design. Effects such as diastasis recti (abdominal separation), pelvic floor dysfunction, changes in posture and alignment, and persistent pain and fatigue can shape what is feasible day to day. Some mothers would prefer to work remotely to save commuting time, while others seek greater schedule flexibility to accommodate these bodily changes, but many feel unable to voice these needs to their employers due to concerns about how their professionalism will be judged.

There is also evidence from other studies that motherhood can slow or stagnate career progression, a prospect that weighs heavily on many women during family planning. Henrik Kleven of Princeton found, in his work with the National Bureau of Economic Research, that much of the remaining gender inequality in labor market outcomes in developed economies stems from “child penalties” that are driven less by biology or policy than by persistent social norms around gender roles and parenthood.

If professionalism is defined by appearance and by how effectively caregiving can be concealed, workplace design itself warrants reconsideration. When women take time out of the labor market during the years in which careers typically accelerate, because they have had children, they become underrepresented in senior leadership. As a result, organizations systematically draw from a narrower talent pool – often without recognizing how structural expectations, rather than individual capability, are shaping who advances within the organization.

Women are an essential part of the labor market, and organizations benefit when more women remain in the workplace and advance after becoming mothers. Research coauthored by Yeqin Zeng of Durham University Business School shows that companies led by women are less likely to get into debt.

Implications for Leaders and Organizations

If companies want to retain women in the labor market, they need to revisit how professionalism is defined and evaluated. This begins with auditing expectations that tie competence and commitment to appearance. Careers unfold in different rhythms and pathways, yet progress is often judged through visual stereotypes rather than meaningful actions and contributions. When a woman feels she must hide her exhaustion in order to be seen as competent, the issue lies not with the individual, but with the norms that shape how competence is assessed.

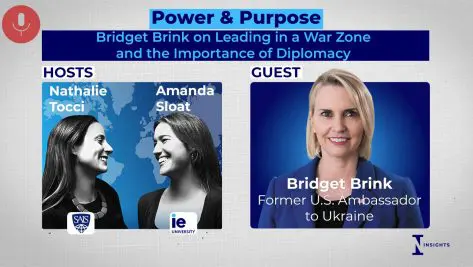

Virtual work likewise requires reconsideration. While remote and hybrid arrangements are often presented as family-friendly, they can reproduce the same visibility pressures in new forms. Making cameras optional in meetings, questioning assumptions that a tidy background equals professionalism, and normalizing interruptions can go a long way toward reducing unnecessary strain. The widely shared BBC interview in which a guest was interrupted by his children was met with affection rather than judgment. But it’s worth asking whether the reaction would have been the same had the interviewee been a mother. If such moments can be celebrated on live television, organizations can extend the same tolerance in everyday working life.

Leaders can play a key role in setting these norms. When leaders allow their own caregiving realities to be visible – and do so across genders – they signal that professionalism does not require the erasure of life outside of work. This kind of representation makes it easier to bring their full selves to work.

Organizations do not need further evidence that women matter in the workplace. What is often overlooked is the cost of asking employees, both women and men, to compartmentalize their identities in order to belong and progress. Companies that embrace women after they become mothers not only preserve valuable experience but also cultivate leaders who are grounded, focused, and unwilling to waste effort and resources pretending to be someone they’re not. In fact, leaders who don’t feel the need to compartmentalize their identities and can act authentically are more likely to make ethical, transparent decisions.

This is not about whether mothers can be professional. They clearly can be, and are. The real question is whether organizations are prepared to accept that careers now unfold differently, and that many professionals – men and women alike – follow non-linear paths. Ambition, contribution, and long-term value do not always look the same.

© IE Insights.