There comes a point in the life of every technology when it ceases to function as a safe haven and begins to operate as a marketplace. It happened to radio when advertising came to bankroll programming, to the early web when banners colonized once-sparse pages, and to social media when personal feeds quietly transformed into curated shop windows.

A similar shift now looms over the first generation of conversational artificial intelligence. Still far from technological maturity, these systems are likely to appear, in hindsight, strikingly primitive. Yet ChatGPT, the platform where millions have entrusted fragments of their private lives, from tentative medical queries to personal confessions, is preparing to introduce advertising directly into our conversations.

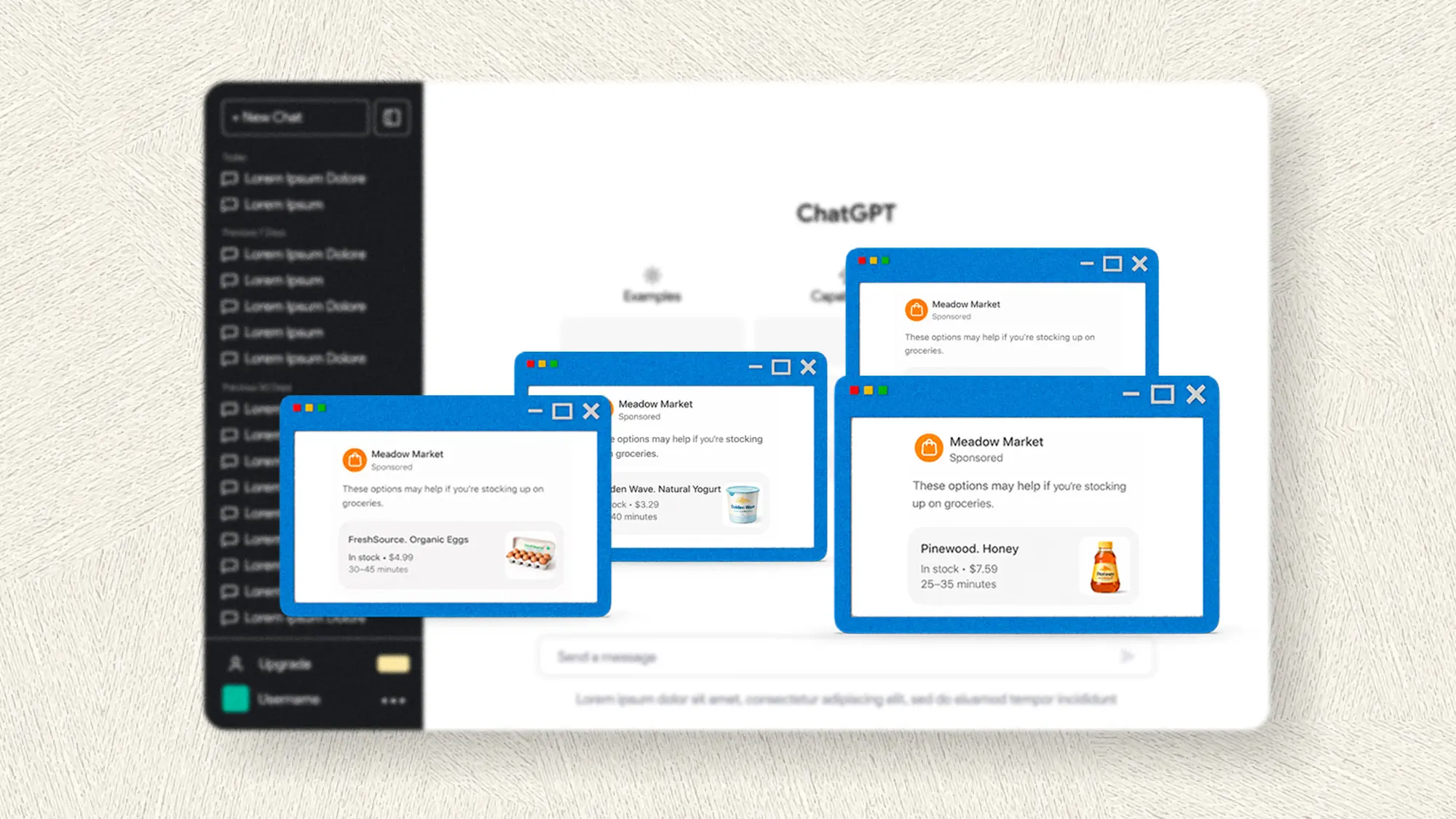

OpenAI presents the introduction of adverts as an approach “grounded in core principles.” It clearly states that “ads do not influence the answers ChatGPT gives you,” that “ads are always separate and clearly labeled,” and ultimately concludes with “we never sell your data to advertisers.” On the surface, these assurances all sound convincing in a corporate policy statement. The reality, however, is much more disturbing: an agent trained through billions of interactions will now show you advertising suggestions grounded in the deeper context of your questions, in the same conversation previously reserved for help. This is not merely a banner on the side; it is a context-sensitive recommendation embedded directly into interactions where information and trust once reigned supreme.

History suggests caution here: many others started out with the same supposedly good intentions, and we know what happened after that.

The question is not just whether OpenAI says it will not influence its answers. The real issue is whether users believe it. When a machine starts feeding your information flow with products relevant to your queries, the line between useful recommendation and commercial push becomes blurred. Even the most basic academic research on adverts in chatbots reveals that although users may not immediately detect advertising, once they are aware of its presence, they perceive the system as being less reliable and more manipulative. Integrated advertising breaks the illusion of a neutral space, even when the text of the response is not actually “purchased.”

The perception of manipulation, not the actual manipulation itself, is the real existential risk for this industry.

The situation is exacerbated in a context where the monoculture of a handful of large platforms dominates not only search and information infrastructure, but also digital privacy. How many people come to ChatGPT seeking relief, advice, or practical solutions without thinking that “there may be a commercial incentive behind it”? What has become a space of tacit reassurance in a relatively short time can evaporate almost instantly when, in the same conversation, a promotional pitch comes right after a personal question.

Some even compare this strategy to “the ultimate goal of mass television advertising”: reaching our homes, our mental couch, with content designed to influence us. Television used to have a few channels; now, artificial intelligence has millions of private conversations it can sneak into.

There are already clear signs of unease. Some users have reported what they perceive as advertisements even in spaces that were promoted as being ad-free, generating debate about the boundaries between contextual recommendations and truly intrusive advertising. This is not a minor issue: we are talking about hundreds of millions of people who use these systems weekly, not as technical experiments, but as everyday decision-making tools.

A logical consequence of this erosion of trust is the flight to alternative solutions. There is already talk of power users migrating to local models, open-source solutions, options that ensure confidentiality, or chatbots hosted on private clouds, precisely to escape the commercial logic that permeates centralized digital platforms. If the person who helps me plan a trip also sells me hotels and insurance, how do I know that the recommendation is not influenced by commercial incentives? That once peripheral concern now moves squarely into the core of the relationship between user and assistant.

Another factor also comes into play here: the cultural and regulatory differences between the United States and Europe. In Europe, regulations such as the GDPR and greater sensitivity to privacy and user protection mean that integrating advertising into services used in high-stakes contexts could meet with more resistance and be subject to closer scrutiny. In the United States, where digital culture has historically been more permissive toward pervasive advertising, acceptance may be greater, although no less critical from the standpoint of informed users. Legislation and public sensitivity could define two clearly distinct experiences of conversational AI use.

Ultimately, the question is not whether advertising will damage the user experience (which seems likely), but how it will transform our perception of what a trusted digital assistant is. When every useful recommendation is perceived as a veiled commercial opportunity, what was once a space for selfless assistance turns into an open marketplace. And trust, once broken, is extraordinarily difficult to regain.

Platforms that today promise that “ads will not influence responses” should know that the perception of manipulation, not the actual manipulation itself, is the real existential risk for this industry. Once AI ceases to be a collaborative tool and becomes just another monetization channel, where does that leave us? And above all, how many people will decide that their next assistant is one they control, as opposed to one that spends its time trying to sell them things?

In a world where we already distrust social media algorithms, introducing advertising into the artificial intelligence systems that manage our thoughts and intimate decisions is not just a change in business model: it is a breach of the relationship of trust with the user. And once that contract has been broken, it cannot be restored with well-meaning words or promises labeled “clearly identified ads.” This is what is at stake.

© IE Insights.