Apologists argue that AI will liberate us from repetitive tasks, opening time for meaningful and creative work. Yet it is difficult to take this narrative of liberation at face value, since technological innovations rarely reduce workload. Even so, the data is hard to ignore. More than half of all new articles published online fall into the category of “AI slop” – mass-produced, low-effort, and inane content that is bringing the signal-to-noise ratio of the internet to new lows. Meanwhile, the share of students who report using AI for their assignments has climbed from 66% to nearly ninety percent in just a year, with text generation and editing as the most common uses.

When does efficiency begin to undermine the focus and effort required to learn? That question brings to mind a warning David Foster Wallace gave his 2005 Literary Interpretation class: “I draw no distinction between the quality of one’s ideas and the quality of those ideas’ verbal expression,” his syllabus declared. This principle shaped his teaching and ultimately the essays and postmodern fiction that still influence culture today. Severe as that stance may sound, it does articulate something important: thinking is shaped by the labor of expressing it.

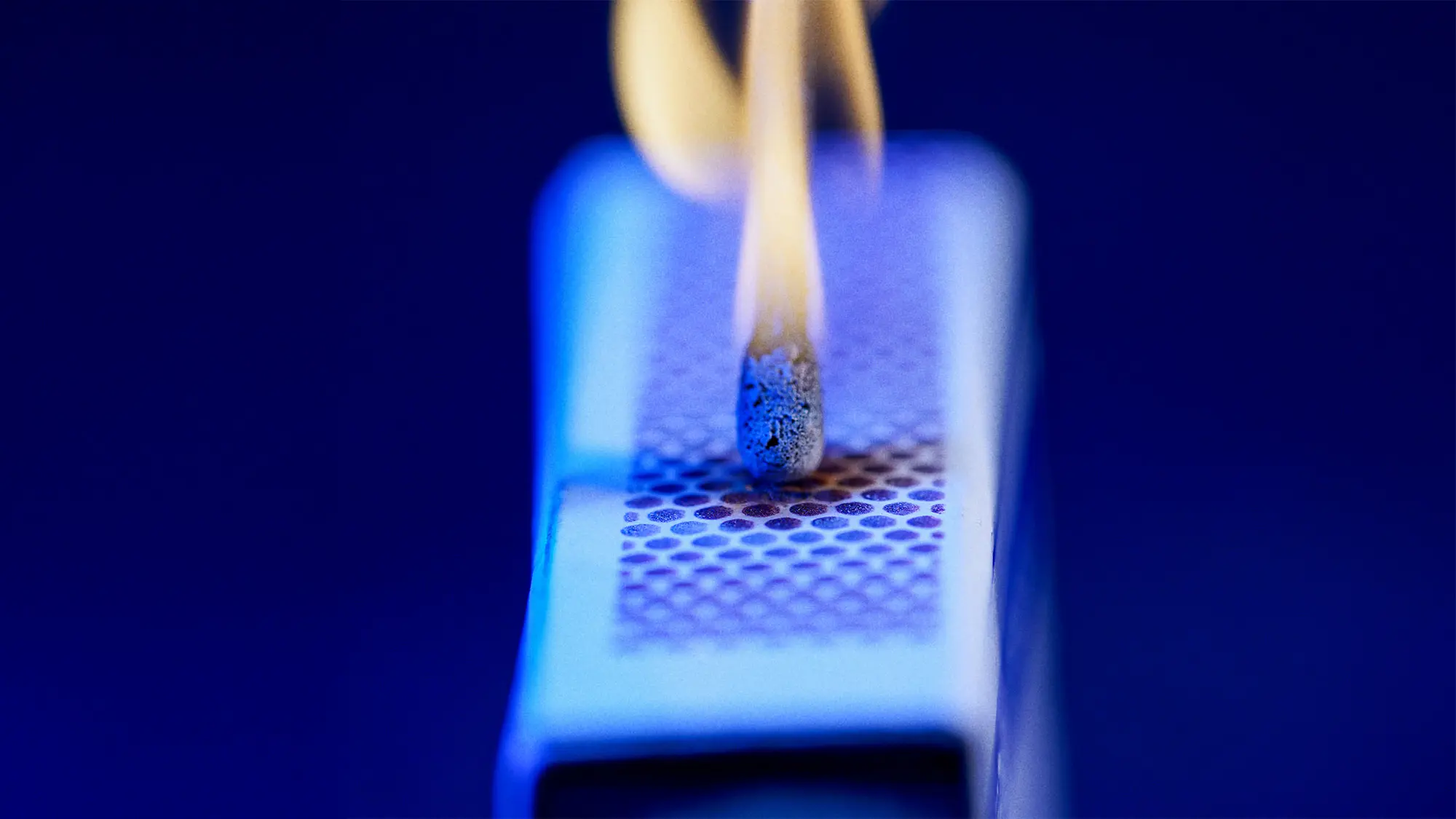

The page is a workshop. Outlining, drafting, cutting, expanding, starting over, circling back, and rearranging are among the tools by which language is brought into contact with the world. As with a carpenter working a chisel through the knots of wood, writing relies on friction to sharpen thought. To disengage from that process is not only to step away from writing, but from the thinking and learning that writing enables. Learning is, after all, a collective struggle to articulate reality.

It’s worth remembering that writing has never been a neutral conduit for thought. It has always emerged from the demands of bodies, voices, and social arrangement. Each technological change in writing has changed how we understand the world. To understand what is at stake now, when people are disengaging from the work of writing at unprecedented scales, we have to look back at how writing first came into being.

Writing began as a system for tracking transactions in the expanding cities of ancient Sumer and the Akkadian Empire. Over millennia, it evolved into what Peter T. Daniels and William Bright in The World’s Writing System, a comprehensive reference work detailing a vast array of writing systems, describe as: “a system of more or less permanent marks used to represent an utterance.”

Stripped of abstraction, this definition locates the origin of writing in the lungs, throat and mouth, casting it as the afterlife of a bodily act. Seen in this way, every written mark, whether pressed in clay, carved in rock, captured on paper, or on our modern-day screens, becomes a trace of that act.

The initial records that would eventually turn into the writing systems that we rely on today rarely included word separations, punctuation, or other marks to indicate pause. The earliest ancestor of our alphabet was written in a continuous script, requiring readers to find and impose pauses and emphasis. Scholars take this to suggest that reading was primarily a social, oral performance practiced by a minority. Aramaic and Hebrew, the Bible’s oldest languages, make no distinction between reading and speaking: the same word names both acts.

In his Confessions, the theologian and philosopher Augustine of Hippo recalls coming upon Bishop Ambrose reading quietly in Milan in 384 A.D., and finding it remarkable that, “His eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still.” Modern historians take this description as evidence that silent reading was unusual enough to be remarked upon in a culture where texts were usually narrated communally and aloud, by readers who carried meaning through breath, tone, pacing, and voice, before text began its inward migration.

Experienced readers like Ambrose might have been able to understand meaning silently, but most still did so through the voice, by reading aloud or reciting from memory. As innovations like the codex format, the Gutenberg press, and the expansion of universities led to the gradual rise of literacy and individual book ownership, punctuation began appearing in texts. Encoding onto the page what oral narrators had originally conveyed with their voice, the page became a kind of breathing score, showing the rhythms of breath and emotion as they fall and rise through the work.

Historical phases of transition always produce interesting artifacts. In ancient Greek, high, middle, and low dots signal pauses of different length and flavor. In Hebrew cantillation at the end of the first millennium, diacritical symbols guided the rise and fall of voice. Much more recently, the modernist poet Charles Olson’s 1950 manifesto Projective Verse argued that breath should be a poet’s central concern, rather than rhyme, meter, and sense. To listen closely to the breath, according to Olson, “is to engage speech where it is least careless – and least logical.”

There’s no easy shelter in This Connection of Everyone with Lungs, Juliana Spahr’s collection of poetry written in the aftermath of the attacks on the Twin Towers. Responding to collective grief and the inescapable awareness of shared air, her poems consider how breath binds us across distances both intimate and vast, whether we acknowledge it or not.

“As everyone with lungs breathes the space between the hands and the space around the hands and the space of the room in and out” the collection’s title poem keeps repeating. Like smoke rising, that line expands outward with each stanza to take in rooms, buildings, neighborhoods, cities, oceans, and finally the mesosphere.

Devoid of punctuation, the stanzas rush onward without interruption. Read silently, the distances between self and world collapse seamlessly through this momentum, suggesting they form one interconnected whole. Reading aloud, something else happens. Without marked pauses, readers must break the poem’s surge forward to draw breath. Those involuntary interruptions make palpable the limit of breath against the poem’s imagined continuity.

The body both enables and limits expression, and Spahr’s poem makes that dependence felt directly. Lexicon of the Mouth, a theoretical book in which artist and sound technician Brandon LaBelle considers how the voice brings the self into relation with its surroundings, articulates this paradox. “A bodily missile,” LaBelle calls the voice, one that “has detached itself from its source, emancipated itself, yet remains corporeal.”

The voice is always slipping away. It leaves one body to arrive in another, carrying traces of its origin. That movement, emerging, departing, arriving is the story of writing.

“I have to change to stay the same,” painter Willem de Kooning said. For educators, writers and editors, the task is to support this ongoing dance of revealing and concealing, so writers can remain recognizably themselves while also growing beyond themselves. At its best, writing (and by extension learning) enables a return to the self that is never the same as the one that began.

Such work yields writing alive with paradox and contradiction. But reaching that place requires tolerance for slowness, resistance, and the stubbornness of thought. As AI companies promise smoothness and ease, the challenge before us is to protect the friction through which learning and selfhood take shape.

© IE Insights.