Politics have become increasingly entwined with our everyday lives, a shift that has been particularly evident in the world of sports. If Bad Bunny’s appearance at the Super Bowl did not make this clear, the Milan Cortina Olympics drove the point home.

Despite IOC President Kirsty Coventry describing sports as “a neutral ground” in her speech at the opening ceremony, it was clear from the start that these Olympics would be a hotbed of controversy. Indeed, they may be remembered more for politics than anything else.

Much attention has focused on Russia and Ukraine. Vladimir Putin’s government has long exploited sports to stoke Russian nationalism, and this time it did so despite the nation’s ongoing Olympic ban after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Some Russian media outlets have outwardly labeled the 13 “Individual Neutral Athletes” from Russia as the “Russian team”. Government officials have more broadly framed Russia’s exclusion from the Olympics as evidence that the event has been corrupted by the West.

Meanwhile, the IOC sparked controversy when it disqualified Ukrainian bobsledder Vladyslav Heraskevych for wearing a helmet covered in images of fellow athletes and children who have been killed in Putin’s war in Ukraine. Top international sports officials now seem open to ending Russia’s ban under the premise that sport is apolitical.

Striving to keep politics out of sports, however, was not the attitude of the attendees at the opening ceremony who booed Vice President JD Vance. The political volatility in the United States has spilled out into a public criticism of US Olympian Hunter Hess by President Trump after the athlete seemingly disapproved of his policies. Other athletes spoke out, and American fans in attendance expressed both pro-Trump and anti-Trump sentiments.

ICE’s presence in Italy also raised controversy. U.S. Olympic officials changed the name of a hospitality space for American athletes from “Ice House” to “Winter House” to avoid possible confusion or discord.

Within Italian politics, the Games also became a political flashpoint. The day after the opening ceremony, an estimated 10,000 protestors took to the streets of Milan, partly over concerns about the environmental impact of the Olympics. Clashes broke out with police, leading Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni to call the demonstrators “enemies of Italy”.

Politics have clearly raged at the Olympics, but this is no exception for a sporting event steeped in political history. Indeed, just four years ago, the United States, Britain, and several other countries staged a diplomatic boycott of the Winter Olympics in Beijing to protest the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghurs. The narrative around the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang largely centered on North Korea’s participation and the presence of Kim Jong-un’s sister, Kim Yo-jong.

In fact, Milan Cortina and these other recent editions of the Olympics do not come close to qualifying as the most political ever. This title might instead go to the 1936 Berlin Olympics, also known as the Nazi Olympics.

The Nazis shamelessly exploited sports to promote their political goals, going so far as requiring top German athletes to support Hitler’s regime or risk disqualification. The Nazis also used sports to marginalize minorities, in particular Jewish athletes, who were banned from membership in sports organizations.

Such discrimination sparked an international boycott movement. The United States took the idea of staying home very seriously. However, U.S. Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage opposed the boycott, insisting that the Games should be apolitical. The United States finished in second place in the medal count behind Germany.

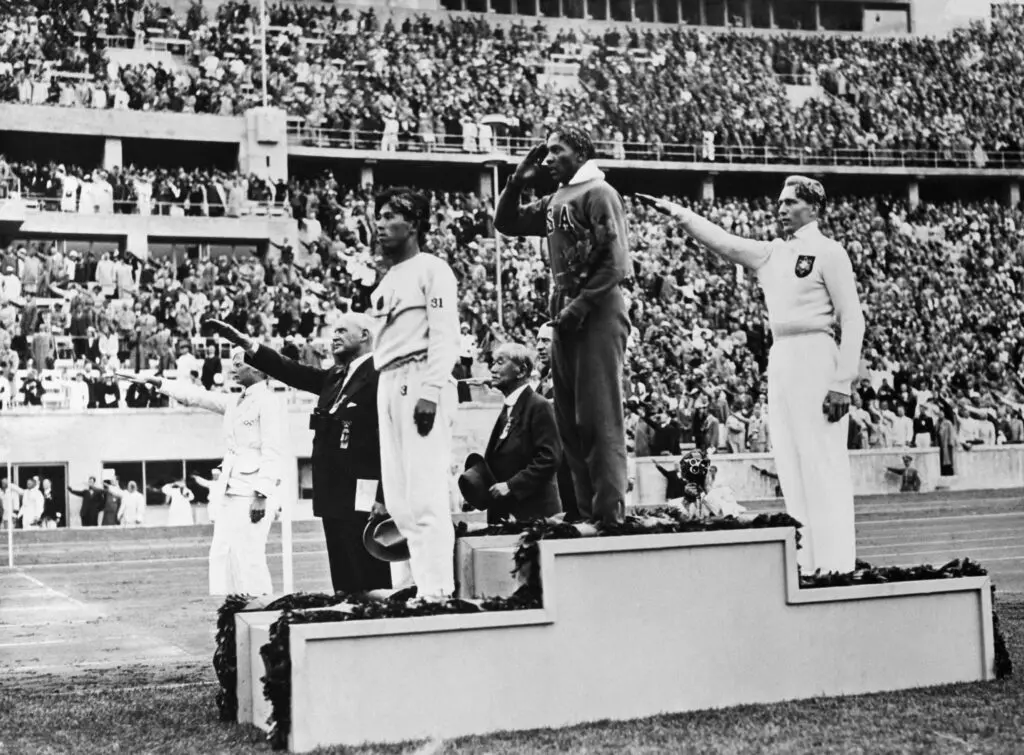

The gold, silver, and bronze medal winners in the long jump competition salute from the victory stand at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. From left, Japan’s Naoto Tajima (bronze), USA’s Jesse Owens (gold), and Germany’s Luz Long (silver).

The Nazis also introduced the torch relay to the Olympics. At the time, it gave Hitler’s regime the chance to spread Nazi propaganda through numerous countries in Eastern Europe that his military would soon occupy. The torch relay now stands out as an iconic Olympic tradition, but it should also remind us of the danger of letting dictators hijack international sports to pursue their own political ends.

The 1968 Mexico City Games also have a claim to being the most political in history. This time, the IOC resisted international pressure to ban apartheid South Africa from participating. Avery Brundage had risen to the position of IOC president, and he again insisted that the Olympics were apolitical. However, facing a potential massive boycott, the IOC ultimately decided to exclude South Africa from the Games.

The 1968 Summer Olympics featured other major political controversies. Local student activists tried to use the spotlight from the event to draw attention to the repressive practices of the Mexican government. Possibly fearing that the Olympics could be disrupted, the Mexican regime cracked down on the protests in brutal fashion. Mexican security forces killed an estimated 200 to 300 people, and thousands more were rounded up and imprisoned.

However, the 1968 Summer Games may best be remembered for the protest by track stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos after the 200-meter final. Standing on the podium to receive their medals, they raised their gloved fists in the air as the U.S. national anthem played. The protest sparked widespread outrage back home, with many also defending their actions.

The award ceremony of the 200-meter final at the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games. From left, Australia’s Peter Norman (silver), the USA’s Tommie Smith (gold) and John Carlos (bronze).

More recently, the 2014 Sochi Olympics stand out for their politicization. After an underwhelming performance at the Vancouver Olympics in 2010, Putin’s government implemented a massive state-sponsored doping program that resulted in Russia finishing first in total medals in Sochi.

Besides serving as a propaganda tool for a cheating authoritarian government, the 2014 Games proved political in other ways. The construction of sports venues and other facilities gave Putin the opportunity to make Russian oligarchs wealthier, strengthening elite support for his regime.

The Sochi Olympics also featured controversy over anti-gay laws in Russia that were enacted in late 2013. Former President Obama chose not to attend the event, but he announced a U.S. delegation that included tennis legend Billie Jean King and two other openly gay American athletes.

Shortly after the 2014 Sochi Olympics, Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea in violation of the Olympic Truce – a tradition that dates back to 776 BC and was revived in 1994. Putin also broke the Olympic Truce on two other occasions: when he invaded Georgia on the opening day of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics and when he launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine four days after the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

Putin may invade other countries around the time of the Olympics because he sees the event as a useful distraction. Another possibility is that he might prefer to launch invasions when he expects nationalism in Russia to be artificially high, as studies show is the case during international sporting events.

The IOC might claim that the Olympics are apolitical, but politicians, athletes, and other actors commonly use them for political purposes. The reason is obvious: they provide a global spotlight and a platform for political unity and rivalry to be expressed. The Olympic Games matter too much to the world to just be about sports.

© IE Insights.