For long enough now, the conversation has not been whether or not we should adopt AI. It is pretty clear it will change the world and find its way into almost every aspect of our lives – from grocery shopping to art creation, from task management to education. I have written before about its potential usefulness in supporting student creativity, but now that students are using it more and more, we as educators must manage its integration well. The challenge – from kindergarten to university – is now how best to integrate AI into existing academic practices. How can we help students develop a discerning, effective, and ethical approach to this new technology? Not to mention the technologies that will surely follow. How can we help students make use of it, without making themselves useless?

I believe that the answer is to take things old school. Already, there are scientific studies that point to the cognitive decline of minds thanks to AI use. In her co-authored research “Your Brain on ChatGPT,” MIT Media Lab’s Nataliya Kosmyna asked participants in 32 regions around the world to write essays with the use of ChatGPT, then only using Google’s Search engine, and then without using any online resource. Monitoring brain activity, the study found that the GPT group had the lowest neural engagement and became lazier with each subsequent essay. It was a small sample size, but the authors wanted to publish quickly in an attempt to draw more research to the issue.

As an older and perhaps more skeptical academic myself, I appreciate the benefits I gained from writing essays at University with a pile of library books and textbooks on my desk. Forced to seek, select, analyze, paraphrase, to disagree, I was afforded the chance to come up with my own take on a subject. It goes without saying that this would take about a week to do 0.000001% of the work ChatGPT can now do in less than a second. But this human effort to gain knowledge and understanding is also an education in the act of work and resilience – the value of personal research as a means of personal development.

In my art classroom, I am constantly pushing my students to develop this creative research process, and it is becoming more and more difficult. Where students should be digging deeply into ideas, sketching, photographing, writing – they now want an initial idea to immediately lead to a finished piece of work, to skip the research phase almost entirely. But in art, as in many disciplines, it simply cannot work this way. A student working with oil paint for the first time, for example, must research and build their own bank of knowledge about how the paint behaves, how textures are built, how it feels in the transfer from brush to canvas, the effect of a little impasto, of layering. The physical research does not come with an AI shortcut.

It is important to create an environment where struggle is not avoided.

The research that art students put into building their skills is more than just what becomes visible in their finished piece of art. In fact, the effort that must be put into the building of such skills is not always easy – it can be far from effortless. It can be downright difficult. But these are what UCLA psychologist Robert Bjork calls “desirable difficulties” – the work of retrieval, practice, and problem-solving that deepens understanding and makes knowledge stick. One could say that it is the struggle itself that makes an education. A student who has a bin full of crumpled paper (these days perhaps more metaphorically than not), who drafts and redrafts, this student is not wasting time but strengthening mental, physical and emotional habits that will help them think critically later. When a fully written essay or a fully constructed artwork can appear in seconds at the click of a button, what is lost are those desirable difficulties. Short-term efficiency can lead to students who are less prepared to handle the very complexities that AI cannot yet – might never be able to – solve.

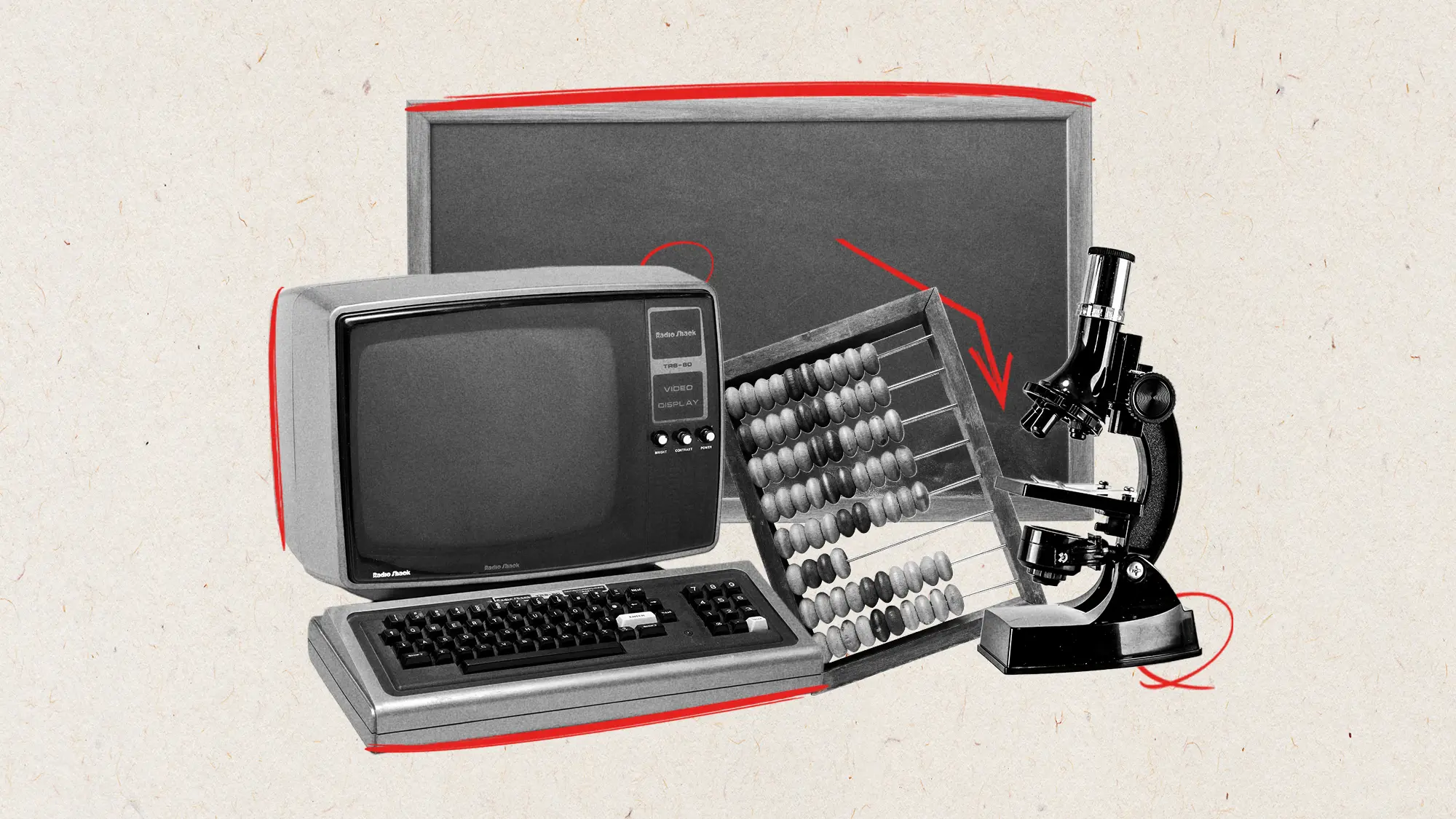

Previously, one of the most controversial pieces of technology added into the classroom was, of course, the humble electronic calculator. This began in the 1970s and there was the expected debate about how students’ learning of mathematics would be impacted: was it the end of skills development or an opportunity to learn how to navigate the tools of their likely future? It should sound familiar. What happened, of course, is that the integration of calculators into the classroom evolved slowly, and thus the fears around a total loss of mathematical ability at the hands of the machine did not come to fruition. Perhaps a key lesson here is that the calculator did not replace the learning of basic arithmetic skills and exams were and still are designed with calculator and non-calculator skills in mind. Still today, the functions, both basic and complex, that a calculator carries out are nearly always understood in theory before they are turned over to the machine. Of course, what we need to keep in mind with AI is the sheer speed of its adoption, and from the student level up.

A student recently told me that they wished they’d dropped art from their class schedule – because it was bringing down their grade average. (This is not a new phenomenon, of course.) Many students measure subjects by the grades they yield and project how those grades might help their future endeavors. But the real gains are found, in my opinion, elsewhere. In art, progress is slow, uneven, and often downright discouraging. Yet that very difficulty is the way students build patience and self-knowledge alongside technical skill. They learn to struggle with materials, to make sense of artistic traditions, and to let ideas mature over time. It is the same in other disciplines. If we want students (of any and every level) to develop habits of inquiry and perseverance, some projects must be deliberately designed without technological shortcuts. That means essays written from books and notes, experiments and equations carried out by hand, businesses and buildings modeled with pencil and paper. We must not forget the importance of learning through effort.

At the start of this article, I noted that AI will no doubt find its place in all of our lives. This is true. But if students are to use it wisely, they must first learn how to think and create without it. Those who grow up with both experiences – working through problems by hand and turning to AI when appropriate – will be better prepared to know how to identify when taking a shortcut serves them and when it cheats them. They will be able to make an ethical choice regarding when AI can be a tool that assists and when they must present something that is entirely their own.

It is thus the responsibility of educators to curate these experiences and develop curricula with the aim of combining the new and the old. Likewise, it is important to create an environment where struggle is not avoided but highly valued and discernment is taught alongside technical skill. I do not want my students to eschew AI altogether. I want them to be able to know when to reach for it, and that when they do use it, they are doing so from a position of knowledge and strength. The key is learning, of course. And this comes from personal experience. You cannot truly appreciate the usefulness of a hammer until you have tried to push the nail in with your thumb.

© IE Insights.