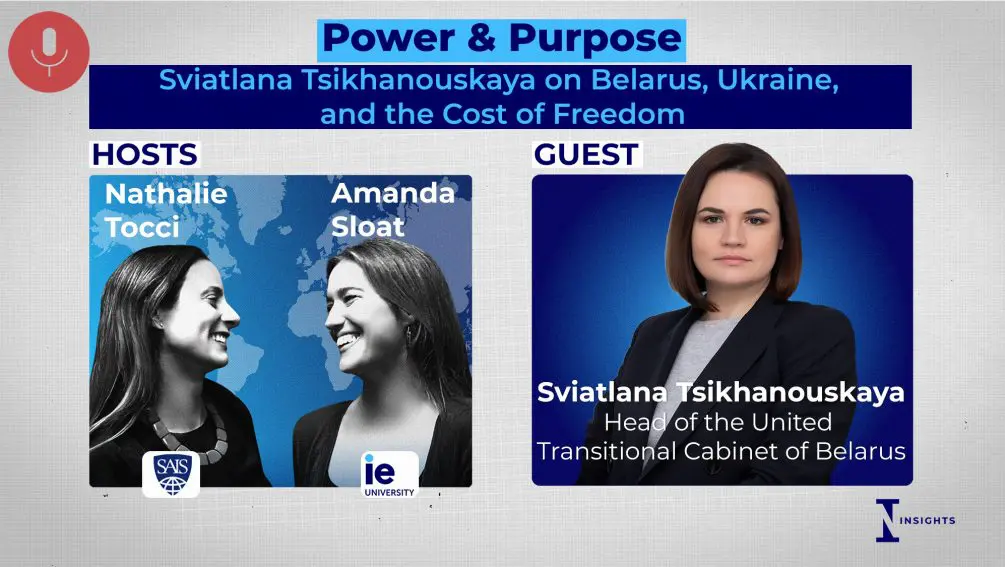

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya on Belarus, Ukraine, and the Cost of Freedom

Exiled Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, widely acknowledged as the winner of the August 2020 election, joins Amanda and Nathalie for a conversation on democracy, courage, and the cost of freedom. She reflects on her unexpected path from teacher to political leader, the intertwined struggles of Belarus and Ukraine, and what it means to keep hope alive in exile. From fear and resilience to the power of women’s leadership, Svetlana offers a unique view of what it means to fight for a country’s future.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is the Head of the United Transitional Cabinet of Belarus.

© IE Insights.

Transcription

Amanda Sloat

Welcome to Power and Purpose. Today, Nathalie and I are delighted to be joined by Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the leader of the democratic opposition in Belarus. The former teacher and stay-at-home mom assumed this role ahead of the 2020 elections in Belarus when her blogger husband and other opposition leaders were jailed or forced into exile.

Although Alexander Lukashenko dismissed her as a housewife and claimed a landslide victory in widely-seen fraudulent polls, Sviatlana was and remains a fierce political opponent. From exile in Lithuania, she unified the opposition and led the largest democratic movement in the country’s history. She established the United Transitional Council of Belarus to coordinate the opposition, and is actively continuing the campaign for a democratic future, the release of over 1200 political prisoners, and humanitarian aid for her country. Sviatlana, welcome to the podcast.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Hello everybody. Good to be here with you.

Nathalie Tocci

Wonderful, Svetlana. So let me jump straight in by asking you a couple of questions about Belarus and your struggle. So, particularly since Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine began, on the one hand, attention to Belarus has increased, and on the other hand, it has decreased. It has increased in the sense that as it has become increasingly clear that Russia is intent on, in a sense. recreating its empire.

It is very clear that Ukraine is one of the targets and that Belarus, in Putin’s eyes, has already been pocketed as one of the colonies. And, of course, Lukashenko is very much part of that endeavor. So on the one hand, it has raised the sort of profile and relevance of your struggle for democracy and therefore also for peace in Belarus.

But on the other hand, it has overshadowed it precisely because all of the attention has been revolving around Ukraine. So I’m wondering if you could speak a little bit about how you understand the connection between the war in Ukraine and the fight for freedom and democracy in Belarus, and how you have navigated this struggle since Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

You know, for me it is so clear that Belarus was for such a long time, like a gray spot on the map of Europe, but not really many people understand that the fate of Belarus and Ukraine are intertwined. We are actually fighting the same enemy with the Ukrainians: the imperialistic ambitions of Russia. Russia doesn’t see neither Ukraine nor Belarus as separate, independent sovereign states.

They see us as their satellites, servants, you know, to Russia. And they don’t think – I mean Russians don’t think – Belarusians and Ukrainians have the rights to choose our future by ourselves. Ukrainians want to join, to return actually, to the European family of countries, the same Belarus always belonged to Europe. And now we want European future for our country.

But the regime made Belarus a co-aggressor. And Lukashenko allowed Russian troops to invade Ukraine from our territory. But Belarusians didn’t agree with this. Only 4% support sending Belarusian troops into the war. Hundreds of Belarusian volunteers fight for Ukraine, shoulder-to-shoulder with Ukrainians and many citizens resist the war from inside Belarus. And of course, our position is clear that peace in Ukraine must be done on Ukraine’s terms.

And we fully understand that the victory of Ukraine will affect the situation in Belarus as well, because the victory of Ukraine will weaken Putin’s regime and hence Lukashenko’s regime, and it will be a moment of opportunity for Belarusian people again to resist inside the country and to get rid of Lukashenko’s regime. So all this 30 years of Lukashenko’s government, he dragged us into Soviet Union past while Belarusian people want to go to the future, to a European future.

Nathalie Tocci

Yeah. And by the way, are you confident that victory is going to come?

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

I think that there is no other choice either for Ukraine nor to the rest of the world, because now Ukrainian war is not only about Ukraine. It’s not only about, I don’t know, Belarus, it’s about the entire region. If we show regimes, tyrants, terrorists, that democracy doesn’t have enough power to resist, these regimes will spill over. Because dictatorship is like cancer. Until you cut it to the very last cell, it will spread further and further. So that’s why the victory of Ukraine is part of the security architecture of the whole region. And it will be the fact that democracy has teeth, dmocracy has power and boldness in order to counter dictators.

Nathalie Tocci

By the way, I love this image of dictatorships being like cancer, that the cancer spreading actually makes me think of another very uncomfortable connection going on here. As we know, there are growing, let’s say illiberal, and perhaps even authoritarian trends in Western societies as well. I’m wondering how you have handled and how you look at the connection between the president of the United States, and Lukashenko.

I’m not trying to sort of imply here that Trump is a dictatorship, but to be very, very clear, it is clear that he doesn’t have many problems in dealing with dictatorial leaders, whether that is Putin or whether that is Lukashenko himself. So, how has the Trump factor affected the way in which Belarus pursues its struggle for freedom?

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

First of all, I have to say that for all these five years since our uprising in 2020 started, relations with the United States always were vital. And we have been enjoying bipartisan support for Belarus through the Belarus Democracy Act. For example, there was support from administration and Congress. We understand that Trump is more transactional.

So our task is to get him interested in the Belarusian case, and his interests might be to bring change for Belarus to be like a peacemaker, to be like the UN in Belarus. And, of course, we already saw the impact of American leadership in very concrete terms because thanks to the firm actions of President Trump and his team, dozens of political prisoners were released from Belarusian prisons, including my husband Sergei.

And this was not just politics. These were real lives saved, families reunited after years of separation and of course, you know, for me personally, I will never forget the moment when my children finally saw their father again. And for this, I’m deeply grateful. And they know how many other families feel the same way. But at the same time, we must be very clear about Lukashenko.

He’s not changing. He remains a dictator at home, destroying any independent voices, closing media, criminalizing even the use of the Belarusian language, for example. My message in the Belarusian case to Washington is very direct: any engagement with Lukashenko must be principled. There can be no rewards or no concessions until all political prisoners are freed, repressions are stopped, and Belarus has a real path to new democratic elections. Firmness and unity are the only language.

For us it’s extremely important transatlantic unity. I mean European and American. So as I say, let President Trump be President Trump. He wants to bring peace all over the world. He sees his mission in this.

Go ahead. So many people will be grateful for his achievements. But again, there shouldn’t be signs for dictators that they will be appeased, that it’s normal what dictators are doing. But through releasing of people, this success in releasing Hamas hostages, it’s really significant. But afterwards, we have to understand that the USA is a democratic country, where human rights are respected and, for all these years, repressed nations always looked on the USA because it was like our lighthouse ahead.

And we just always told that we want the same situation as in the USA. But what I see, it was the first part of your question about changing of the moods in the democratic world is that it’s really so. I see how propaganda poisoned the minds of ordinary people. That they perceive, people who believe in democracy, that look, why do we have to interfere into nations who have problems with the human rights, like, enjoy your lives.

You live wonderfully in a democracy. Why do you have to care about Belarus? About Ukraine, you know, but this is a rotten perception. Because dictatorship in one country might infect other people with dictatorship. And sometimes. I even here that “maybe we need to have like smart or light dictatorship in democratic countries because it’s easier to rule, you know, it’s easier to make decisions”.

But people don’t always understand what it means to lose democracy. It’s so easy to lose, but it’s so difficult to gain, to get it back. It costs lives. It costs freedom. It costs tears. So cherish what you have. Praise your leaders who are bold, who are principled, who are decisive and stay dedicated to the values that your countries, your nations are based on.

Amanda Sloat

Well you certainly embody many of those values and Nathalie and I are keen to get more into that and the details of your struggle. You talk about living in dictatorship. I suspect many of our listeners have never actually met somebody from Belarus. They will not have visited Belarus. And so I’m interested in hearing about your personal story.

What was it like growing up as a child in a country like Belarus? Could you talk about politics at home with your family? And I also understand that you, like me, benefited from the experience of studying abroad, that you, among other children who had been affected on the margins of the Chernobyl disaster, had the opportunity to go to Ireland, which then opened up English and a broader world to you.

So I would be interested in hearing about the early life of Sviatlana, both the good and the bad of being a child in Belarus. And then this experience that got you out of Belarus for the first time.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Look, I was born in the Soviet Union, and we enjoyed three years of independence in Belarus until Lukashenko came to power. And I have to say that the story of every nation is different. In the case of Belarus, people after the collapse of Soviet Union were so poor. There were so many problems that people were just not interested in politics.

People were surviving. And in this situation, people chose a very populistic person in Alexander Lukashenko, who promised a better life, European perspectives, a bad economic situation. People just believed and voted almost blindly honestly speaking. And very fast, Lukashenko managed to build a dictatorship that is based on military support. He built his personal security apparatus, he dismantled parliament, he started to rule on the basis of fear and step by step, it’s like in a swamp.

You are not realizing that you are in the dictatorship. But once if your interests are becoming not the interest of government, you realize that you don’t have rights, that the laws are not working for ordinary people, that you don’t have a voice. If you object to anything, you will be landed in prison immediately. And our parents generation, they really couldn’t resist because they said they were surviving.

But new generation who maybe started to travel to see how other countries live. They started to understand that our country with wonderful people with good geographic position, could live much, much better. But this is because of this dictatorial leadership who is tying us to Russia. They’re not giving us opportunities to develop. Of course, you mentioned Ireland and, the possibility for me to see other countries was a real huge impact on me.

And many people, children from Belarus. actually visited different countries, Italy, Spain, Germany. And they brought their experience back to Belarus. And when they grew up, they understand that, look, something is wrong with our country because many other Soviet Union countries developed much, much better than Belarus. Let’s take Poland orl Lithuania, they gained their independence from Russia.

And they just economically developed, people feel wonderfully enjoying democracy. And our country because of poor government, because of poor management, is stuck in the Soviet Union times. So of course, I remember my first visit to Ireland when I saw, you know, I was a child, I saw shops full of food and clothes. This is what we never had in Belarus.

I saw smiling people. In Belarus, people were surrounded with all those problems, trying to survive and didn’t have like a wish or desire, you know, to smile or to greet each other. And I was shocked by the kindness of people where they want to take care of others, not only about themselves. So it was like cultural shock for me.

Of course, you start to compare with what you have in Belarus, and that’s when the internet came. And then step by step, a new generation realizes that we can live much better and we want a better future for our children. So that’s why I insist so much while communicating to democratic world that while punishing Lukashenko for his crimes against humanity, for human rights abuses, we have to keep borders open for people, for people to have possibility to travel, to keep this people-to-people contact. Because: isolate Lukashenko, don’t isolate people.

This is our credo because it’s Lukashenko’s propaganda to always say that “nobody needs you in the West, it’s rotten West. We have to keep closer to Russia.” But there is another world, a democratic world, a wonderful world. And people have to see this world only just to compare.

Nathalie Tocci

You know Sviatlana, can I tell you a story? Actually, Amanda doesn’t know this, and I can’t remember if I ever happened to tell you. There is a by now no longer child because he has actually just turned 18, Belarusian boy who was one of those Chernobyl boys that used to come.

He was an orphan. And he used to come to Italy, staying with a family that is very close to ours. He actually then fell ill, he basically had cancer.

And in that period, he kept on coming back. It was a real struggle to getting the Belarus regime to allow him to continue to come back. But it was incredible to watch him, as you were saying, kind of open his eyes up to a different world. And the amazing part of this story is that on the one hand, he has now in September just turned 18, and he is no longer under the tutelage of the state, and he managed to escape.

He used to only be able to come here with a guardian. And he has now managed to escape. So he’s now free. He’s here. He’s in Italy. He’s here for good. And this is really what my question was, he is still really struggling with fear. On the one hand, he’s an incredibly brave boy.

And he’s gone through so much and yet especially now that we see him a lot, I can so tell that he is just scared. I mean, he is scared of what might happen to people that he still knows that are still in Belarus. So I guess it’s the kind of rather vague and perhaps slightly question that has to do more with emotions than with anything else.

But how do you deal with that fear? Because fear is such a key component of a dictatorial regime. I mean, they kind of instill it into your brain. And how do you how do you deal with it? You know how to overcome it.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Well you¡r absolutely right. You know, fear paralyzes people. And when 2020 happened in Belarus, when we saw how people for several months in a row were deprived, were not afraid of the regime, we felt such a strength inside. And then we saw how the regime brutally crushed people, put people in prisons, were beating them, and we saw how fear was returning to people.

Of course, regimes are based, they’re built on the feeling of fear. Even those who are living in exile at the moment. And I have to remind that since 2020, up to 1 million Belarusians left Belarus because of repressions. We still have friends, relatives in Belarus and people hiding their faces, even being abroad, because their relatives can be detained by this regime.

So this lawlessness and this brutality of the regime already spreads on Europe on other countries. Repressions became transactional. People are declared extremists and terrorists and put on the Interpol list. And even while you are abroad and while travelling you can be detained by Interpol because you are in this red line terrorist list. The regime is depriving Belarusians of their documents, of their passports.

So people live in fear inside the country. People live in fear abroad. But this possibility, when there was necessity to overstep your fear, to put your global or national aims higher than your personal fear. This is real strength of the nation. Because of course it’s easier to say, look, I am afraid and this is why I’m not going to do anything.

But when you understand that you’re doing this for your children, for your country, you cannot you shouldn’t concentrate on your personality, on your emotions. You just you have to work hard to bring attention to Belarus, to help those people who are in trouble, to communicate to other governments and societies, even if you are scared.

Amanda Sloat

Well, let’s come to 2020 and how you became what you have described as an accidental politician or accidental leader. And just one note for our listeners who are probably younger than us in many cases, we’ve referred to Chernobyl a couple times, for those who do not know, that was an explosion of a nuclear power plant in 1986, in what is now Ukrainian territory.

And that led a number of charities to then follow up with children and others who were affected by that. But Sviatlana, you were working as an English teacher, you met your dashing husband who was a nightclub owner. You had two children. You were living life. So how do you go from that to becoming this globally known democracy campaigner?

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

You know, my decision to step into politics was absolutely spontaneous. I never could imagine that I will be in politics. When my husband Sergeiwas jailed because he dared to run against the dictator, I took his place out of love to him, to my nation. I won the elections in 2020. The results were stolen. But what followed wasn’t just about me.

It was a national uprising and millions of people stood up together. I had to leave the country for my children’s safety. But I continue to work because I know what we are fighting for; for dignity, for freedom, for normal life. And of course, we all want to return home to a free and democratic country. And of course, it was difficult path, the political path, because I started to learn everything from scratch.

Maybe I’m lucky because the best politicians of this world were my teachers, you know, presidents, prime ministers, ministers. But it was really again, it’s about fear. I was scared to meet high-ranking politicians because I didn’t know how to behave. I didn’t know protocol. And just I realized I’m representing the whole nation, the voice of Belarusian people.

But, you know, when life puts you in such circumstances where you have to learn fast, where you have to overcome your emotions and fear, you just do this because you have to, you don’t have a choice in this situation. And I have to say that till now I have this imposter syndrome. I haven’t graduated from any political university.

Sometimes I realize that maybe my knowledge is not enough for perfect communication. But I see how people respect my path. People respect the Belarusian nation. And I’m so proud to represent Belarusians and the brave actions, their brave fight. Still, I’m not confident while speaking publicly or giving interviews. But, you know, you have to do this, just do it, you know you have no choice.

And that’s why, of course, I wouldn’t be able to do it myself, but it’s about my team. It’s about the persons who are supporting me. You just realize it. Your face. You are a leader of a wonderful nation. And this nation at last has a voice. And this voice has to be strong, has to be powerful, confident. And I’m trying to do my best.

Amanda Sloat

So just for our listeners and correct me if I have the facts wrong. Your husband became a blogger, and became a very popular blogger in Belarus, interviewing people about their lives, about what was happening in the country. He and a number of others then challenged Lukashenko, very active in the democratic opposition. Lukashenko put your husband and the others in jail.

Your husband was not able to run from jail, so you ran in his place. Like you said, Lukashenko stole the election. You were then forced to go into exile into Lithuania, from where you launched this global campaign for Belarusian democracy. And your husband in 2021 was sentenced to eight years in prison. And as you mentioned earlier, was just released this June after five years in jail.

So did I miss anything there, is that the general timeline and how you ended up in a sense taking over what had been your husband’s mission initially and turning it into a global campaign?

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

It’s a short description.

Amanda Sloat

The very short condensed version for those who may not be as familiar with Belarusian politics as they should be.

Nathalie Tocci

A very long and complicated story.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Yeah. The only thing is that my husband was sentenced to 19 and half years in jail. It’s not eight. So the terms for activists, brave Belarusians, are rather big, rather long. For example, one of my comrades, Masha Kalesnikava, she was sentenced to 11 years in jail. She is woman who tore her passport when the regime tried to expel her out of the country.

So, my husband spent five years in jail, in solitary confinement. And the two and a half last years he was kept incommunicado. For those representatives of the democratic society who don’t know what incommunicado is, it means that he was in full isolation. The lawyer is not allowed to visit you, no literature, no parcels, no visits, no phone calls, no information.

So you have nothing. Well, you don’t know what’s happened. And, outside the letters and the regime is doing this to break people, they want to erase them from public life and to persuade them that nobody cares about them. “Look, you don’t get letters, the lawyer is not visiting you, and you everybody forgot about you.

You are abandoned. You are forgotten. The world doesn’t care.” So this is how the regime wants to break people inside the country, or inside the prisons.

Nathalie Tocci

Yeah, Sviatlana coming back to this. So in a sense, this is a story about your husband who is a male leader. And because of these circumstances, you then step in and you are a female leader. What is your sense of what you as a woman leader add to this, what are the main strengths that have come with you being the face of the democratic opposition as being a woman leader?

And what are the challenges that you have had to face as a result of it, especially coming from a regime which is an extremely vertical, chauvinistic and dictatorial regime. And normally dictatorships are led by men.

Amanda Sloat

Well, and clearly a dictator who underestimated you and dismissed you as just a housewife.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

So first of all, the fact that I was chosen as the leader of Democratic Forces, actually as the President of Belarus, was a clear signal to the regime first of all, who has since the beginning told that our Constitution is not for women. Women cannot lead the country. It’s nonsense. And Belarusians showed to the regime look it’s possible.

We are voting for a woman. And in that moment, our women actually in 2020, they stood instead of our men because it were first men who were beaten brutally, who were detained by the regime. And they didn’t know, these policemen didn’t know how to treat women who stand in beautiful white dresses with flowers in front of these brutal policemen.

We show that we are peaceful. We just want changes in the country. But then women also started to be detained. But maybe the most important Belarusian initiatives now are led by women. Women are multitaskers, women are maybe better in marathons, in long distance. We are not concentrated on our ambitions in school. Maybe like mothers, we want better for our children.

And it means better for our country. We are not competing with each other. We complement each other. We want to helpeach other. And, of course, I don’t want to say that men’s world is worse, you know? But it is more about competition. For women, it’s about supporting each other.

And so I’m so grateful that I did so many women’s breakfasts, women’s meetings, where we can share not only political science, we can talk about the best clothes shops, you know, but of course, it was a very big shift for Belarusian women because in most Soviet Union countries, they’re mostly patriarchal societies where women’s place is in the kitchen or with children in churches, but not a leading position.

And now it became so evident that Belarusian women are not worse than Belarusian men, and in some extent, even better. That’s why I think that after changes in Belarus, there will be no questions if women are on the same level as the men. That we already proved this. I cannot say that, I had some problems or challenges on the international arena being a woman, I never felt any humiliation or whatever because I was a woman.

Some men are looking from above, but they respect bravery. They respect our fight. So maybe it is somehow compensating the men’s view on all the women. But of course, I see that this attitude toward women is changing all over the world.

And we see these women leadership movements, and we see how women are supporting and helping each other. So the world has changed. And the women understand we are not the people of second rate. We can do more. We are leaders. We are the brave, just we always had a lack of space to show it.

Amanda Sloat

Well, I think women helping women is important. And, Sviatlana I was telling Nathalie my favorite memory of you was when I was working with President Biden in the White House. And he came to Poland in February 22, just a couple of weeks after the war in Ukraine had started, March of 22 and gave a speech in Warsaw.

You were there at the speech. I had very much been hoping to get the two of you together for a meeting in person, and unfortunately we couldn’t get the logistics sorted out, and I felt terrible. And President Biden’s main assistant also felt terrible. And she said to me, “let’s get them on the phone”. And so I was able to call one of your colleagues.

And then I walked into President Biden’s private office on Air Force One before the plane took off and handed him the phone and said, “Mr. President, I have Svetlana on the phone”. And he was so pleased to talk to you and to express his support for you and the Belarusian people. And I share that just as a small anecdote, it remains one of my proudest staffing moments from my time in the White House of really being able to do something important and facilitate a conversation that I know the president wanted to have. And that was also very important to you at that point in your political leadership, development and broader democracy struggle as well?

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Oh, yes Amanda, of course I remember the story and till now we are so grateful to you because we understand that it was not necessary for you to do this for us, but it shows your heart also felt pain for our country, you know, for our struggle. You made it for us as well.

It was such an important step. And the conversation actually in media, it was so interesting, showed that while President Biden so seldom call into anybody, it might be something urgent, phoned in from the plane. So, these steps are so important. And sometimes people don’t understand how impactful, what an important role they are playing in connecting people.

And actually, it was a movie that was short about the Belarusian fight, it is called “The Accidental President”. And this moment is shown there, so everybody who is interested can watch it. And the conversation with President Biden is shown there.

Nathalie Tocci

Phenomenal. Coming back to your I think wonderful analogy of women being better at marathons. The personal hardship that you have been through. I mean, of course, you were not the one in jail, but to know that your husband, your loved one was and you had to leave the country, you with your children, how have you dealt with that, that very personal marathon?

What have you done to keep yourself, in a sense, mentally healthy, physically healthy? While you were constantly… I can think of my husband being in jail, I don’t know how I would deal with it. How did you deal with it? You know, I’m not trying to suggest to you that it’s worse being out of prison than being inside prison.

But if it’s your loved one that is incommunicado, it must be just such a horror to deal with.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

No of course, it’s not easy to work knowing that your beloved is being tortured, is being humiliated physically and mentally in prison, and psychologically. And when you don’t know when they will be released. But what you know is that you have to do everything possible to release him and other people as soon as possible.

I have to say that, of course, this gap between those people who spent five years in jail and those who were fighting for these five years is really huge. Because while protest, while relocation or the beginning of the war in Ukraine, people who were free, we experienced the emotions together. We saw Bucha in Ukraine. Together we saw how Belarusians are being killed by this regime.

Together we formed our government in exile. We always communicate and coordinating our actions. And for people in jail, it was just short messages. The war has started. Elections in the USA. Or Russians war ship was bombed, you know, but there were no emotions in this. And I see how my husband, for example, has to learn so much about these five years.

But I think I’m afraid that he will never be able to catch these emotions that we experienced through all these years. People after prison, they are exhausted physically, but most of them are not ruined, they are not broken. Prison leaves deep marks. Sergei is still recovering his health. At the same time, he has immediately returned to what he has always done, speaking the truth about Belarus, supporting those who remain in prison, reminding the world that our fight is not over.

And so on, so forth. But, you know, for these five years you’re simultaneously working hard, trying to be everywhere in all the countries, simultaneously trying to arrange the work of democratic forces, trying to be a good mother as well. Because, you know, I really feel so sorry that I didn’t manage to pay so much attention to my children.

They were growing like grass themselves this year. And it is always a feeling of guilt for people in prison. Guilty that the democratic world cannot do enough to help Belarusians to change our country. Guilty that not all the institutions work properly. Guilty when new people are detained. So it’s always such a huge burden on your shoulders.

But you understand that you have to do this. Even after my husband is released, I cannot fully enjoy this happiness because still there are so many children in Belarus growing up without their parents, many wives and husbands waiting for their loved ones. You feel guilty because your husband is with you. So that’s why I just want to feel this moment of full happiness when I am not guilty,

I don’t feel guilty for everything around. Just when we can rebuild our country together. When we can hold new elections in Belarus. When people are happy, returning home. But now my life looks like this.

Amanda Sloat

Really it’s almost unimaginable what you have gone through. And as you alluded to earlier, I’m sure your heart has really been with the Israeli families over the last two years who have had their loved ones in prison. And I’m sure you also can relate to what they are going through in these recent days of reuniting with their loved ones.

So, Sviatlana we could continue to talk to you for many more hours. We like to end the podcast on a positive note. You were alluding, just a minute ago, to wanting to feel joy and happiness. And of course, that being a conflicted emotion, given everything that you are still fighting for. But I’d like to ask you very simply and narrowly tell us something that has brought you joy in the last week or so.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

This will not be something personal. It’s again about our fight, but seeing how people sometimes feel fatigue, that Belarus is a little bit abandoned, overshadowed. You know, overlooked. Recently, I spoke with a young Belarusian volunteer who helps families of political prisons, and she told me, “we don’t know when freedom will come, but we must live as if it is already near”.

You know, that’s inspired me a lot. It reminded me that even in the darkest time people find courage to care for one another, even being themselves in pain. They’re trying to support other people whose grief is bigger. So my joy is not in big events, but in these small acts of solidarity, in the small moments of happiness, you know, hugging children or seeing families reunited.

So of course, we want more of these moments in our lives. But, I have to say that as long as people believe there is a future for our country and for democracy globally.

Amanda Sloat

I love that there’s lots of people that are facing struggles for democracy in their own country, feeling overwhelmed by the challenges that they face. And I think they can take inspiration from your resilience, your campaign and your wise advice here.

Nathalie Tocci

And you know Sviatlana, actually listening to you, my two-word take away actually from this conversation: So it has really struck me, and I’d love to leave our listeners with is that hope and courage are really the two sides of the same coin. And, you are such a voice that speaks of courage. And it is that courage that you really embody, I think really leaves us with a sense of hope moving forward. So thank you so much for being on the show with us. Thank you, Sviatlana.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Thank you.