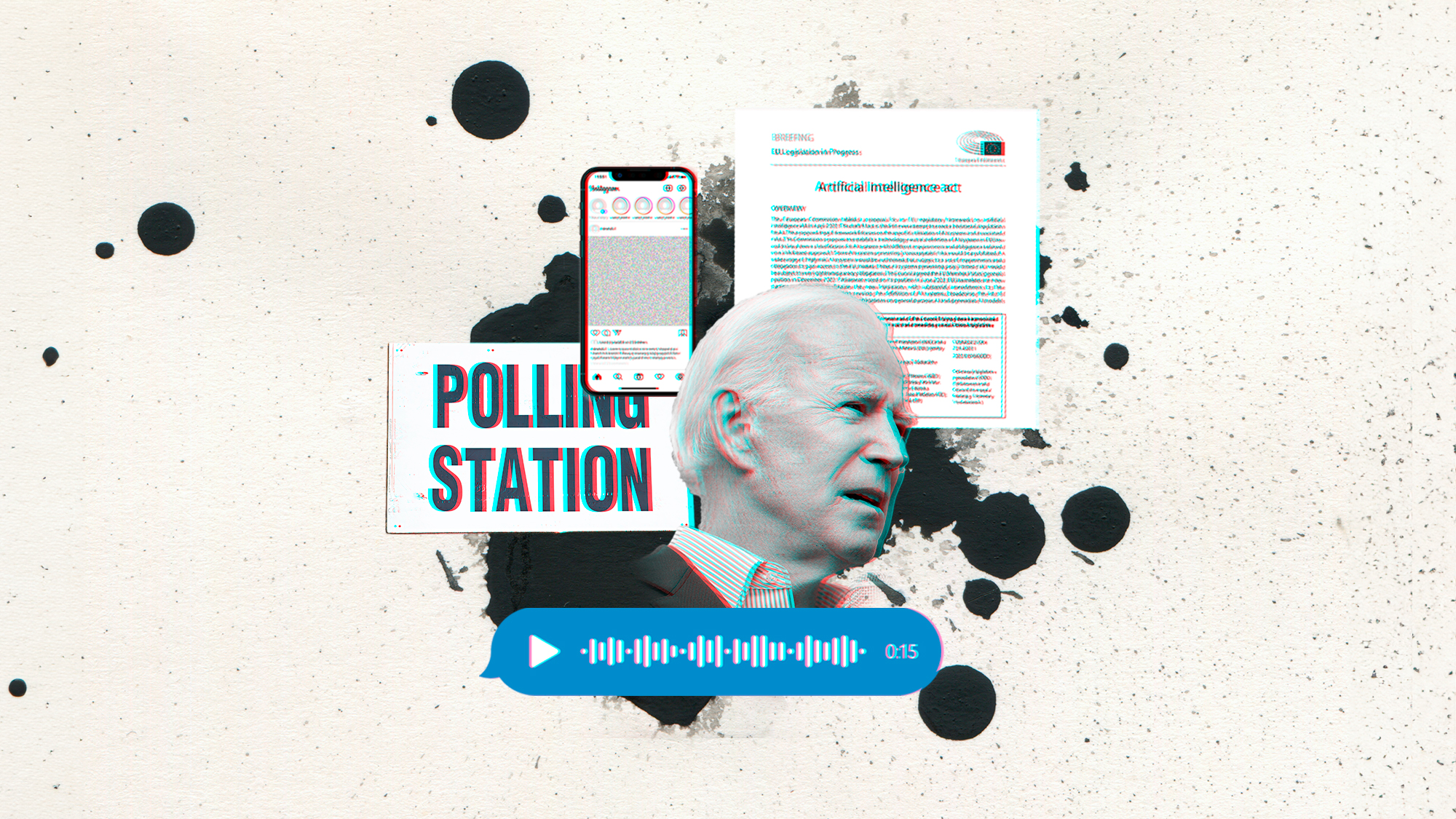

On January 21st 2024, just three days prior to the New Hampshire presidential primary, residents of the New England state received a phone call from President Biden. During this call, they were urged by the President himself “to save their vote for the November election.” Yet, Joe Biden never recorded that message; instead, a robocall used artificial intelligence to mimic his voice with the intention of dissuading Democrat voters from casting their votes in the primary.

This is not an issue solely relegated to the United States. Citizens from more than 70 countries around the world head to the polls this year, and we are likely to witness the largest use of deceptive AI in the history of humankind thus far. From deepfakes that impersonate candidates and election officials to AI-powered bots that provide false or misleading information to voters, AI-based disinformation campaigns are already challenging the integrity of our democracies – precisely at a time when trust in institutions is at an unprecedented low.

The deceptive use of AI poses a particular threat to our electoral processes due to, for example, the fast pace of election cycles. In the lead-up to the polls, there is limited time for debunking and fact-checking before citizens cast their ballots. What happened in Slovakia is a prime example of this. In the days leading up to the 2023 Slovakian parliamentary election, deepfake audio recordings portrayed the leader of the pro-Western Progressive Slovakia party, one of the country’s two leading parties, discussing election rigging and proposing the doubling of beer prices. This fake recording spread rapidly on social media, and ultimately led to the Progressive Slovakia party’s defeat. Some argue that this could have been the first election in history swung by deepfakes.

Sophisticated AI systems are improving their ability to replicate reality, effectively blurring the boundaries between real and make-believe. As noted by Financial Times senior columnist Tim Harford, “deepfakes, like all fakes, raise the possibility that people will mistake a lie for the truth, but they also create space for us to mistake the truth for a lie.” Thus, it comes as no surprise that citizens lack confidence in being able to distinguish between AI-generated and authentic content. A survey by the Center for the Governance of Change at IE University confirms that only 27% of Europeans believe they would be able to spot AI-generated fake content. And, let’s be honest, the fakes will only get more real.

The production of synthetic media such as deepfakes often relies on the availability of vast amounts of personal data, such as videos, biometric data, or voice recordings. This kind of data is now abundant. Social media users consistently prioritize convenience over privacy – as evident from a casual scroll through any Instagram feed, where most citizens seem unconcerned about their digital footprint – and thus the potential for virtually indistinguishable deepfakes continues to rise. Given this seemingly inevitable trend, how can we ensure the protection of electoral integrity and above all maintain public trust in our democracies?

It is much easier to predict the benefits of artificial intelligence than its drawbacks.

First and foremost, we need a governance framework and comprehensive regulations to ensure close oversight. The European Union and the United States have kickstarted this process through the EU AI Act and Biden’s Executive Order on AI, respectively. In Europe, the AI Act has classified systems that can be used to influence the outcome of elections and voter behavior as high-risk, subjecting the producers to specific obligations. In the United States, the Executive Order has incorporated provisions for labeling AI-generated content to inform users of its origin. Additionally, a series of recently introduced bills have focused on addressing deepfakes and manipulated content in U.S. federal elections. Critics, however, do not believe these measures will be sufficient to stop deceptive AI because, for instance, they impose liability only on the producer of the content, not the distributor, and could therefore be ineffective at curbing the spread of fakes once produced.

This is, secondly, why we need further commitments from companies, political parties, and civil society actors. In addition to simply labeling or watermarking AI-generated content, companies – especially tech firms – should urgently deploy mechanisms for detecting deceptive AI content, allowing it to be reported and blocked before it spreads. Social media platforms could consider imposing limits on the quantity of AI-generated content displayed in their feeds, as it only increases the risk of misinformation. Lastly, it is also crucial that political parties establish firewalls to prevent the amplification of deceptive AI content, ensuring that candidates promptly remove and rectify any misleading or fake AI-generated content.

Third, as internet users, we might want to reconsider how we prioritize convenience over privacy in the digital space. The aforementioned survey also revealed that up to a third of Europeans would still use social media apps such as TikTok even if authorities advised against it due to privacy concerns. Our digital footprint serves as a double-edged sword: while it might make life easier – think biometric data to unlock your phone or facial recognition technology to sort your photos – and exciting – think sharing holidays on Instagram or expressing political opinions on Twitter – it also exposes us to the risk of having our personal data used against us, within the context of elections and beyond. If we want to reduce the risk, we might need to reduce the exposure.

These three elements may not be able to stop the harm that deceptive AI can inflict on our democracies – and we should also explore how to leverage AI to defend and enhance these democracies – but we sure stand a better chance than if we just placidly sit as spectators.

It is much easier to predict the benefits of artificial intelligence than its drawbacks. Unfortunately, we know for a fact that generative AI will be used during this electoral year by both domestic and foreign actors with the aim of influencing campaigns, eroding trust in democracy, and igniting political chaos. Considering the remarkable pace at which deepfakes and other synthetic content have advanced over the past year, there will likely be increasingly sophisticated deceptive AI used to disrupt electoral processes – and in a year where more than four billion people will elect their representatives, addressing an ungoverned AI should be a priority for us all.

We have entered a new era, one marked by the growing synergies between society and AI, and this means that embracing both innovation and, crucially, responsibility is a collective imperative. The next step, therefore, is to help address the limitations of existing regulation. Considering the rapid pace at which technology moves, it is imperative that our companies and civil society collaborate and adapt swiftly. The survival and wellbeing of our democracies rely on it.

© IE Insights.