人生在尘蒙 恰似盆中虫

终日行绕绕 不离其盆中…

Humans live in a blinding dust

like insects in a bowl.

All day we go around and around

and never get out of the bowl…

Fragment of a poem by Hánshān (寒山) of the Táng dynasty

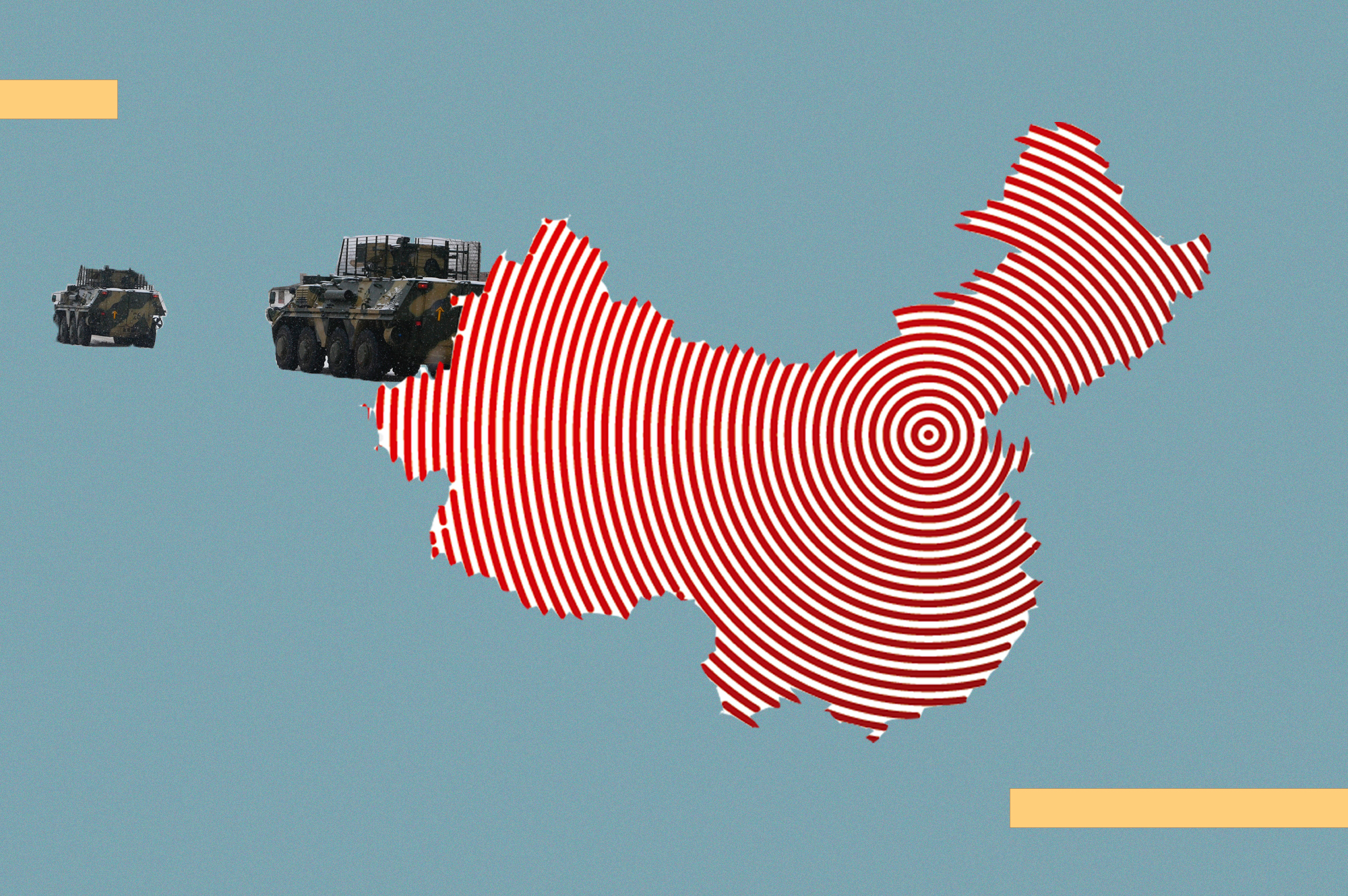

Countries and people alike aspire to be at the center of the narrative. In reality, and symbolically, it is always the center that controls the battle. Its symbolism is hard to avoid. There is little wonder that China has historically called itself Zhōngguó 中国, the country of the center (Zhōng is center, and guó, country). Russia, for a variety of reasons, feels it has lost the center, and wants it back. But, Russia has chosen the hardest path to do so and, in passing, has put China in an awkward position. Everyone is asking the same question: did China know that Russia would invade Ukraine?

The question is a pertinent one, because the answer will determine the nature of international relations for the foreseeable future.

There are two facts that seem to support the arguments of those who think that Beijing was aware of Moscow’s plans to invade its western neighbor. The first is that in recent months, US intelligence had repeatedly warned the Chinese authorities of Putin’s intentions, but they were systematically rejected as unfounded.

Even hours before the invasion took place on February 24, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying accused the White House of ratcheting up tension and creating panic about the possibility of war. Truth be told, the Chinese were well within their rights, because who believes the Americans today, bent as they are on seeing wars where there are none and then, once they have created them, withdrawing after selling the weapons needed to fight them?

The second fact is that on February 4, 20 days before the invasion, a Sino-Russian statement announced to the world an alliance between two major nuclear powers, to the detriment of a third, the United States as well as its sleeping partner, the European Union. A fundamental part of the declaration was its staging: the two countries’ foreign ministers played a secondary role and it was the two leaders, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, who made it clear that the rules of the international game had changed.

All this suggests that Beijing indeed knew what the Americans had suspected and the rest of us refused to consider: that Putin would invade Ukraine.

Nevertheless, something still doesn’t add up.

Russians like to refer to the Hand of Moscow (Рука Москвы) when a story is so implausible as to defy the truth, but for that very reason is indeed true. Because that’s how the KGB used to operate: make it look like they had not been involved, when everyone knew they had been. Thus, Moscow’s hand was behind Trump’s win in 2016. And that hand must also have played a role in that grandiose staging, allowing Putin to simultaneously pass on the message that he was about to make a large military deployment, albeit one short of invasion. The immediate consequence has been that the Chinese, who are not fond of having to make unexpected policy changes, have shifted from unconditional support to simply support because they feel they have been deceived.

By and large, Chinese history and philosophy has ignored what goes on beyond its borders.

The Chinese press described Moscow’s actions as a special military operation (特别军事行动) rather than an invasion, and this is notable because it is contrary to China’s stated principles of non-interference in the internal affairs of sovereign countries. And in the Russian media, since February 25 itself, one day after the invasion, this word “invasion” has also been banned, along with the words “attack” and “war”, in what appears to be an attempt to create an alternative reality for Russians.

How to interpret Beijing’s initial decision to tell its 6,000 nationals in Ukraine to stay put and identify themselves by flying Chinese flags from their vehicles and properties (while most of the world’s nations were evacuating their diplomats and telling their citizens to leave) only to change its mind two days later and advise them not to display any symbols that would reveal their origin, presumably so as to avoid retaliation from the Ukrainians, who now saw China as Moscow’s ally? Is it plausible that the Chinese government would abandon its citizens to their fate if it really thought their lives were at risk?

So what happened? Historically, in situations like this, each side tells their version of the events using their pieces of the puzzle and placing them according to their perceptions and subjectivities in order to create a partial picture (also known as the Rashomon effect). But, there are always pieces — the cornerstones – without which it is impossible to complete the puzzle. In this case, the cornerstone was held by Moscow: nobody was counting on it invading Ukraine. Everybody else was trying to complete another puzzle, based on a different cornerstone, except for, it would seem, the Americans.

That said, surely the Chinese intelligence services, using their satellites, knew about the huge build-up of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border, along with the repeated warnings of their US counterparts. But data is only part of the story. What really matters is how one interprets it. By and large, Chinese history and philosophy has ignored what goes on beyond its borders.

China has traditionally seen itself as the country of the center because its neighbors paid tribute to it in exchange for peace, even if, on a few occasions, it broke this entente. However naïve it might seem now, it is fairly reasonable to believe that Beijing assumed the same from other international players, especially after a joint declaration of mutual understanding. It’s important to remember that outlandish options, such as an invasion, would normally be rejected by the Chinese.

Perhaps those most surprised by the course of events are the Chinese themselves.

Sun Tzu’s belief that it is better to win without fighting is deeply rooted in Chinese politics. Massing troops on a border, from the Chinese point of view, is a sufficiently decisive and coercive measure to achieve certain objectives, so there is no need to actually engage in war. According to Sun Tzu, the best thing to do is to undermine the enemy’s plans (上兵伐谋), then activate diplomacy, (其次伐交), and only go to war if there is no other choice (其下攻城).

In short, perhaps those most surprised by the course of events are the Chinese themselves, who at no time would have thought that things might develop the way they have. For Chinese political scientists, the dominant view was that there would be no invasion. Even Jin Canrong, a well-known political scientist at Renmin University, an institution which has its finger on the pulse of Chinese politics, publicly retracted his prediction that there would be no invasion, apologizing to internet users for misjudging the situation in Ukraine, joking: “My prediction (of non-invasion) was wrong. I impose a three-drink self-punishment on myself!”

Even as late as February 25, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi himself pointed out in a telephone conversation with British Foreign Secretary Liz Truss, European Union High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell, and a French presidential advisor that, in the first of the so-called Five Points, “China maintains that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries should be respected and protected and the purposes and principles of the UN Charter abided by in real earnest. This position of China is consistent and clear-cut, and applies equally to the Ukraine issue.”

Arguing that the Chinese are the first to be surprised is not, itself, without some naivety. But it should be welcomed because China gains, in principle, from its alliance with Russia and loses – has lost – with Russia choosing the route of invasion. In fact, instead of vetoing a UN resolution condemning Russia’s actions, China abstained, along with India, which was actually the nation’s way of saying that it does not agree with Moscow’s approach.

Humanity has always faced problems of a global nature, but they have never been brought to light with such immediacy and intensity as in today’s media age, this new conflict being a prime example and, lest we forget, the Covid pandemic. What also continues to be consistent, and in parallel, is that nations and societies aim for the center within these global conflicts.

Regardless of the creation story, the center is always in dispute. The Greeks said that Zeus released two eagles at the extremes of the universe, the East and the West, and that where they met, a sacred stone – the omphalos or navel of the world – rose, which could be used to communicate with the gods. For the Chinese, the birth of the universe coincides with that of Pan Gu, caught between heaven and earth, which were together, like an egg. The Yang, which was clear, became the sky, and the Yin, which was opaque, became the earth, and in the middle Pan Gu changed endlessly until his wisdom grew the size of the sky and his strength to that of the earth.

So, just like the Greeks and the Chinese, all peoples throughout history have been, in their own way and from their viewpoint, fighting for the center. Why should Russia be any different? Its cosmogony may be more recent, but it obeys the same principle of attempting to explain the birth of the world, and thus its place at the center of it.

In regards to how Russia has cast Ukraine within the Russian narrative of the center, there have been bad performances, bad actors, bad calculations, and overacting, just as in bad movies. Ukrainian President Volodomir Zelinsky told The New Yorker back in October 2019: “Politics is like bad cinema – people overact. Large empires have always used smaller countries for their own interests, but in this political chess match, I will not let Ukraine be a pawn.”

In a nutshell, it might be a good idea if we started acting differently. Rather than placing the center on our own interests, we should remember that the center is our own planet. Perhaps in this way, we could approach important issues such as space exploration or sustainability – in short, the destiny of humanity – a bit differently. And, what if the country that bears the name of the center, Zhōngguó 中国, was the one to lead this shift?

© IE Insights.