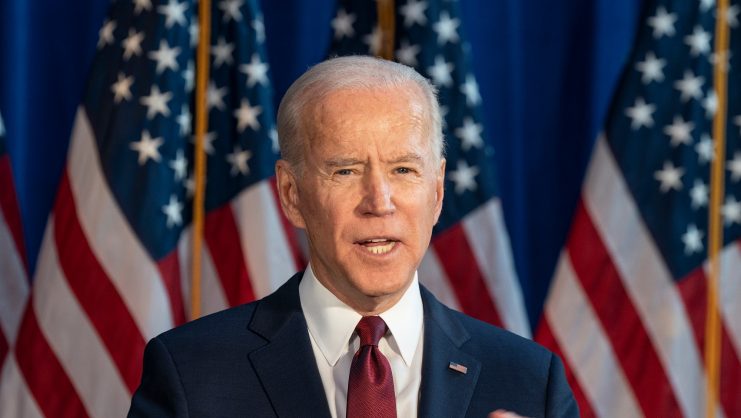

Joe Biden didn’t win the 2020 election because roughly seven million more voters chose him over Donald Trump. Rather, victory came from the 200,000 voters in a few of the so-called swing states. In 2000 and 2016, the Republican candidates who lost the popular vote – George W. Bush and Trump – still won in the electoral college. A similar phenomenon is at work in Congress where Republican senators, who currently control the Senate with a slight majority, represent roughly 20 million fewer Americans than their Democratic counterparts.

So, by minority rule, I don’t mean a minority government in the way that they exist in parliamentary systems, but rule by a minority of the people. The U.S. government, especially the electoral system and Congress itself gives more weight – and therefore power – to citizens residing in less populated areas, putting citizens in urban areas and those states with large populations at a disadvantage. This is why Biden had to win such a large popular majority in order to ensure an electoral college victory and the reason it is so difficult for Democrats to control the Senate. It is also the explanation for how Trump served as president for four years even though most of the country was appalled by him.

A system that advantages some and disadvantages others

In order to comprehend this particularly American phenomenon, it’s necessary to understand how minority rule is baked into the U.S. federal governing system. Fifty states compete for power, but their populations range from 578,000 in Wyoming to 39.5 million in California. Despite these enormous differences, every state is represented by two senators. The situation is exacerbated by the fact there is a greater number of smaller, rural states. And despite the fact that the House of Representatives was originally conceived of as a balance to this representation in the Senate, it doesn’t go far enough to counter the misrepresentation of millions of Americans.

This translates into some pretty big consequences. The biggest recent example being Amy Coney Barrett’s appointment to the Supreme Court, which gave conservatives a 6-3 majority. Four years after a Republican-controlled Senate refused to vote on Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland, claiming it was too close to the election, Barrett’s nomination was rushed through just weeks before the election. On top of that, the move was made during a pandemic and against Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s dying wish.

This choice, that came from a president who wasn’t even himself elected by a majority of Americans will profoundly impact American politics in the coming years. Policies supported by a majority of Americans, such as abortion rights, healthcare, and marriage equality might actually be ruled unconstitutional. While the fate of the U.S. Senate was decided in two run-off elections in Georgia on January 5, it is very likely that Biden will still face a divided Congress leaving him little to no room for any legislative action or means to fix representation issues.

In 1789, the House of Representatives started off with 65 members. This was based on an estimated population of 3.7 million people across 13 states, allowing for one representative for every 57,169 people. The House steadily expanded as states were added and the population grew until the whole process ran aground in the 1920s. Because the 1920 census showed a continuing rural to urban population shift, so rural representatives fought to derail a reapportionment that would render them powerless. They even capped the size of the House at 435 members in a 1929 law.

Gerrymandering, the drawing of district boundaries (often into crazy shapes) in order to favor one party over another, is also to blame for these differences. This happens every 10 years after a census is done and favors the party that controls the state at that time. While the number of states using bi-partisan commissions to draw districts is growing, only 17 will use such commissions to redraw districts based on the 2020 census; it is a minority of the states, many of which happen to be the more urban, blue states.

As long as Republicans continue to be advantaged by the system, they will not want to change it.

California and Wyoming are clear examples of the flawed system. Each one of California’s 53 Representatives stands for 745,000 people, while Wyoming’s one representing 578,000. This Pew Research chart shows how representation varies from less than 600,000 people in some states to as high as over a million. This may not seem like such an enormous difference, especially when compared to the Senate, but the numbers get more concentrated as they are added together for the electoral college.

Each state’s representation in the electoral college is based on the number of senators (2) plus the number of representatives (ranging from 1 to 53), further concentrating the rural over urban advantage. Because of this system, a vote for president in Wyoming, with three electoral votes, counts 3.7 times more than a vote in California, which has 55 electoral votes. The vast majority of the states have a winner-takes-all system, meaning that once a candidate reaches 51% they win all the electoral votes. It doesn’t matter that in 2016, Hillary Clinton won California by nearly 4.3 million votes (61.5% to Trump’s 31.5%), which is higher than the 2.8 million votes she won that national popular vote by.

Possible (but unlikely) solutions

Like all institutional change, changing such an archaic and embedded system as the U.S. Congress is extremely difficult, but the methods include:

1. Increase the number of states

States get relatively bigger as you move west across the United States and while California is not the largest state in terms of area (that goes to Alaska and then Texas), California has by far the biggest population. Texas follows with 10 million fewer people. As long as such a populous state has the same weight as, say Wisconsin, in the Senate, it is punching way below its weight in terms of representation. So, there have been more than a few proposals to divide up the state. “Cal 3” is one such proposal that would divide the state in three that would have been subject to a referendum in the November 2018 election but the California Supreme Court pulled it from the ballot in order to study its constitutionality. Splitting California in three would triple the state’s representation in the Senate. Additionally, if Washington DC and Puerto Rico became states this would also add a few more urban Senate seats.

2. Expand the House of Representatives

As mentioned earlier, the House of Representatives hasn’t grown for over a century. In 2018, The New York Times editorial board advocated to expand the House to 593 members arguing that it would shock the framers of the Constitution that it hasn’t been expanded for so long and that it would bring the United States in line with other mature democracies in the world.

3. All states agree to put their electoral vote towards winner of popular vote

Another idea is aimed specifically at the electoral college. The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is a state-based solution that would guarantee that the winner of the national popular vote would become president. Currently 16 states and the District of Columbia have signed on to this compact, agreeing to put their electoral votes behind the winner of the popular vote. This fix gets around the thorny issue of constitutional change, which would be required to abolish the electoral system entirely.

4. Eliminate the electoral system

There is wide agreement among experts that the electoral college is no longer democratic and should be abandoned, but getting rid of the system requires the arduous task of amending the constitution, with approval of two-thirds of both the House and the Senate as well as 38 out of 50 states. According to a Gallup poll from September, the public agrees and 61% of Americans in support of abolishing the electoral college. However, the fault line is revealed when considering this poll by party affiliation: 77% of Republicans want to keep the system as it is, while 68% of independents and 89% of Democrats want to change it. As long as Republicans continue to be advantaged by the system, they will not want to change it.

When considering these solutions, which are simultaneously controversial and difficult to execute, it is important to note that they will not make much of an impact on their own and should be considered as pieces to a broader solution.

Nothing stays the same forever

This current Republican advantage is not new, nor will it be permanent. For most of its history, the United States has witnessed periods when a party has held more power despite representing fewer people – and this power has more often than not been abused, but with harsh consequences or “backlash.” In the late 18th century, Pennsylvania’s Assembly underrepresented the more radical voices that were in favor of a revolution against British rule. These citizens got their revenge during the Continental Congress by bypassing the colonial assembly and establishing equal representation for each of the state’s counties under the new legislature.

Decades later, slaveholding states maintained minority power via constitutional arrangements such as admitting a balance of slaveholding and free states so as not to change the balance in the Senate. Yet, the admission of California as a free state along with the Compromise of 1850 changed the balance with 13.4 million people living in free states, significantly more than the 9.7 million inhabitants of slave states (3.2 million of whom were slaves that couldn’t vote.) Tensions rose around the Fugitive Slave Act which compelled Northern authorities to capture and return fugitive slaves to their owners as slave states tried to impose minority rule which ultimately led to secession and the Civil War.

Most likely, demographic change is what will end this period of Republican minority rule. The best harbingers of this are Arizona and Georgia turning blue and the once solidly red Texas effectively becoming a swing state in the 2020 election. Many analysts expected these changes would have come sooner but Trump’s 2016 election win proved them wrong. The evolution continues at its own pace and as the U.S. population becomes more diverse, political parties that rely on a predominantly white male base will find themselves at a disadvantage and so Republicans and Democrats alike will begin to make a bigger play for diverse groups of voters. Hopefully, this will do the job of jumbling the electoral map and altering the current balance of power.

A version of this article was published in Spanish with esglobal.

© IE Insights.