They’re confident, articulate, and eager to make an impression. Seems ideal for the workplace but sometimes, those traits hide something deeper. Could your coworker be a narcissist?

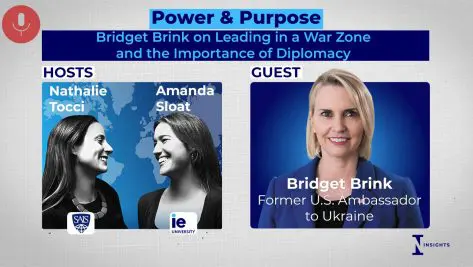

Narcissism has been widely researched for at least half a century, especially in the context of romantic partners. But, as the London School of Economics’ Shoshana Dobrow tells Isabel Berwick in a recent edition of Working It, narcissism is now also a cultural flashpoint at work, primarily because we have become more aware of those traits associated with grandiose self-love, and an idealised view of one’s capabilities can also have a strong impact in the workplace.

That awareness has mostly focused on those in positions of power, but narcissistic traits can show themselves much earlier – even at the intern level.

The concept of narcissism was named after the Ancient Greek figure Narcissus, who became obsessed with his own reflection. Arguably, he not only rebuffed his romantic suitors but also failed to adequately fulfil his job as a hunter, which would have had a detrimental impact on his local community. In today’s professional settings, narcissism continues to similarly strain relationships and put pressure on teams. Individuals with these traits typically respond poorly to criticism, lack empathy for their colleagues, and are willing to manipulate or exploit others for their own advantage. Their presence can therefore disrupt team dynamics and hinder collective performance as they strive for individual achievement. Understanding how narcissism plays out even at the intern level can help companies spot early warning signs before they become leadership problems.

Yet, many narcissists are able to climb the corporate ladder into managerial roles. This is in part because they share characteristics with what many in organizations consider to be relevant for leaders and leadership – namely high self-esteem, self-confidence, and extraversion.

An extensive and growing body of scholarly research has examined how narcissists attain leadership positions, as well as how they behave when occupying those roles. For instance, Barbora Nevicka of the University of Amsterdam and colleagues found that while narcissistic leaders project an image of confidence and authority that makes them appear highly effective at first, their self-absorption ultimately hinders information sharing within teams and reduces overall group performance. What seems apparent from this study and others is that narcissists often present as charming and likable on first encounter, but this good impression wears thin over time, exposing their more antisocial and sometimes malicious behaviors.

Unsurprisingly, once the element of charisma is peeled away, leaders who display narcissistic traits, such as refusing to take responsibility for their mistakes, are essentially challenging for employees to deal with. The contrast between how they are initially perceived and how they actually perform underscores a broader pattern: confidence can be mistaken for competence, with real cost on a team’s effectiveness.

But what happens when the power dynamic is reversed – when the narcissist isn’t the boss but the intern? We are accustomed to thinking of narcissists in positions of authority, perhaps because that is how they perceive and present themselves. But workplace interactions can likewise be disrupted by entry-level workers who consider themselves to be above others.

Narcissism thrives in low-visibility environments.

Internships are an interesting context in which to observe these dynamics because these are opportunities that offer critical work experience and networking possibilities and are often geared towards students in higher education. Many are later hired by the same company after graduation. And of course, because these internships are a possible stepping stone to greater employment prospects, interns often feel pressure to build a positive connection with their managers, mentors, and colleagues. In this scenario, narcissism has the potential to play a crucial role in interns’ perceived employability by affecting the quality of their work relationships.

While much of the existing research on workplace narcissism has focused on those at the top, my coauthors from the University of Bamberg, University of Münster, and emlyon business bchool, and I set out to explore whether the same dynamic at the entry level – specifically among interns – undermines relationships and team cohesion.

To test this, we analyzed data from more than 500 French business school students completing corporate internships as part of their master’s program. Each intern completed a self-evaluation, while their supervisors and two colleagues assessed them on measures of trust, respect, and collaboration.

The findings reveal unexpected nuances that suggest it may be more difficult than previously expected to detect narcissistic traits in junior workers, such as interns. Notably, we found no substantial link between the duration of internships and the impact of narcissism on relationships with supervisors and colleagues. This suggests that time alone doesn’t reveal character, the quality of interactions does. In a workplace culture that prizes speed and confidence, that distinction can sometimes be easy to miss.

This finding points to a broader truth that narcissism thrives in low-visibility environments where success is measured individually rather than collectively. In our study, narcissistic interns were rated less favorably in smaller, possibly closely interacting teams, suggesting that frequent, face-to-face contact makes self-centered behavior more difficult to disguise. Companies that prize confidence and self-promotion may inadvertently reward the very traits that eventually erode trust in teams. By contrast, smaller groups can, by contrast create the kind of visibility that exposes these patterns early. Recognizing them and designing evaluation systems that value empathy, collaboration, and shared accountability can help prevent disruptive personalities from advancing unchecked.

Internships offer a valuable lens for this. For students, they are a test of emotional intelligence – often their first in a professional setting. For employers, they are a preview of future culture. Both sides benefit when confidence is appropriately matched with empathy. Environments that reward humility, feedback, and collaboration can help nurture employees and leaders who elevate others as much as they do themselves.

Educators also have a role to play here, in helping individuals understand the importance of balancing ambition with accountability and respect. Internships are often the first real test of a student’s emotional intelligence in the workplace, their ability to work with others, take and improve from feedback, and to build trust. Helping students reflect on how they behave in a professional setting can make a real difference in the trajectory of their careers.

There is no denying that confidence and charisma are valuable traits. But we must be careful that they don’t tip into self-absorption. The sooner young professionals learn that difference, the better equipped they’ll be to lead – to everyone’s benefit. Students must come to understand that while some narcissists do go on to become leaders, their egotistical behaviors are likely to limit their effectiveness, as well as their personal and professional growth. Confidence and charisma are valuable traits – until they tip into self-absorption. The sooner young professionals learn that difference, the better equipped they’ll be to lead with empathy and integrity.

© IE Insights.