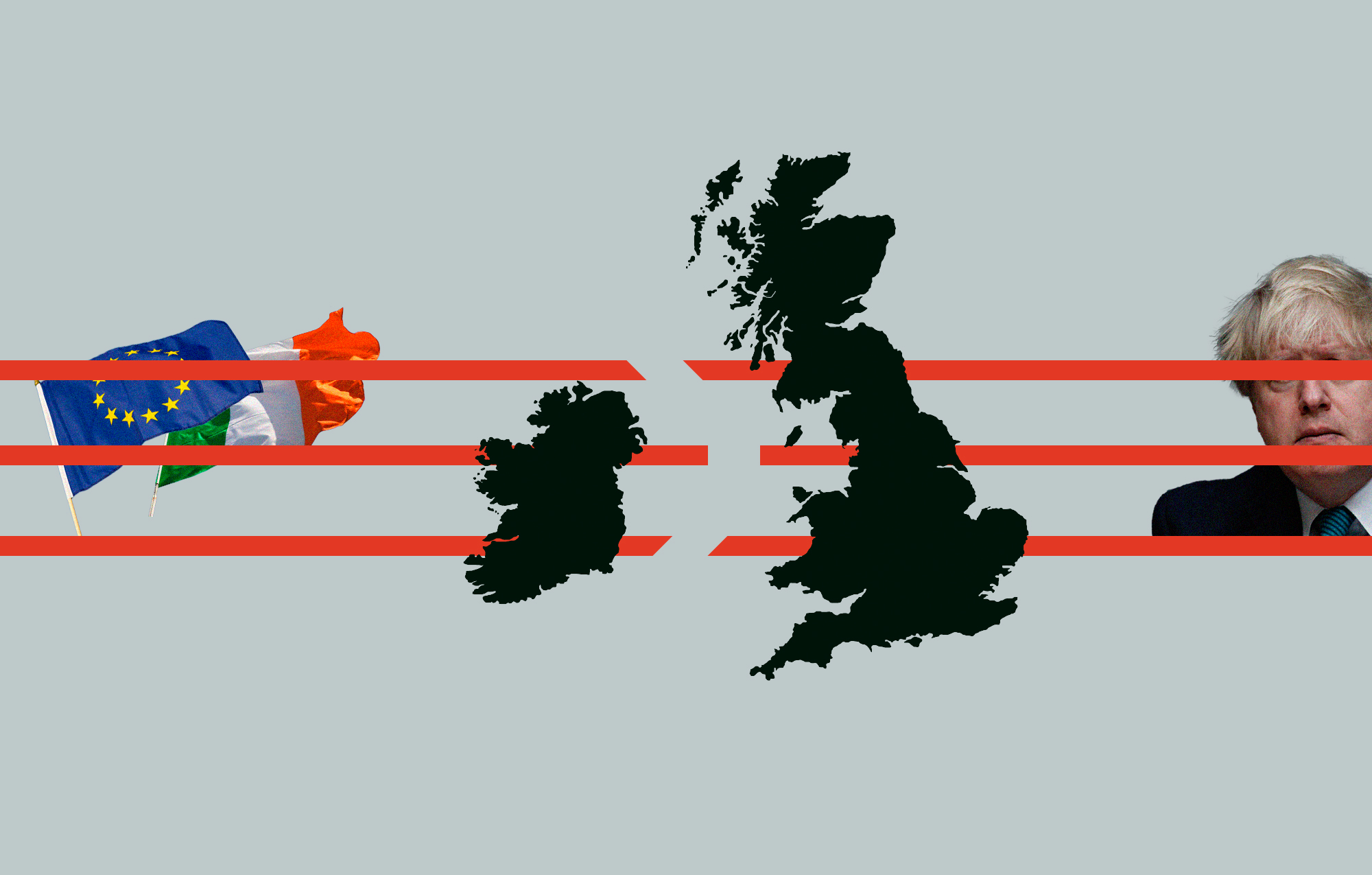

Company makes the journey fly, as the Irish saying goes. However, Brexit, Boris Johnson, and recent elections in Northern Ireland are pushing Celtic folklore to its limits. At this point, it is nearly impossible to plausibly explain why Northern Ireland featured so little in the Brexit public debate and political campaign, just how irresponsible Boris Johnson is being with his dealings with the Northern Ireland Protocol, and how Sinn Féin – the political party once associated with the IRA – managed to win Northern Ireland’s elections only twenty-something years after the Good Friday Agreement. If curses and gifts have always been part of Irish culture, reality these days seems to perfectly feed the myth.

Since 1912, when the independence of Ireland was debated in Westminster and a relatively unknown Liberal MP named Thomas Agar-Robartes proposed that four northern counties remain excluded from the deal, very few political disputes have become as embedded in the collective imaginary worldwide. Wherever the Irish have traveled, stories of the Troubles have followed, fueled by the country’s never-ending literary tradition, the rich musical heritage, an alluring attraction for filmmakers, and the success of the most famous Irish export: the pub. Irish matters, it could be argued, have become the world’s matters.

This all means that a good portion of the globe is following Boris Johnson’s shenanigans in the application (or lack thereof) of the protocol, as well as betting on the political odds in the aftermath of Sinn Féin’s victory. So, let’s try to bring some order to the chaos, starting with Johnson.

Johnson’s Fading Grip on Power

The protocol had been agreed on during the Brexit negotiations as a solution to how to govern Britain’s only land border with the EU: that between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The protocol prioritizes the peace brought about by the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, essentially drawing a customs border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, but after coming into force in 2021 is already under existential threat.

Just a week after 41% of his own party voted for no-confidence in his premiership, in June this year, Johnson presented the law that will allow him to cancel the application of significant parts of the protocol to the Commons. In short, it was the same old “Brussels-sucks-we-rock” tale. In fact, part of the new piece of legislation would unilaterally erase the jurisdiction of the EU Court of Justice (CJEU) on Northern Irish issues. This comes at a time of high tension between the EU and the UK, with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) having stopped a UK-government flight from departing London to take refugees to Rwanda in a dramatic turn of events. As Rowena Mason and Jessica Elgot pointed out in The Guardian, Johnson has recently “gone to war with the law”.

Johnson is seemingly scared that people will finally see the clown he loves to be.

Beyond the obvious question -is there a plan at all in Downing Street?- lies a complicated political ticking bomb that could detonate on one, two, or all sides of both channels, Irish and English. To simplify, there are four areas in which the protocol especially bothers London:

- Customs controls. Unsurprisingly, Unionists in Belfast are not happy with the extra money, logistics, and precious time wasted on a new border with its own state. London now proposes a form of low-maintenance “Green Lane” for products crossing the channel to Belfast while keeping a “Red Lane”, with all EU checks, for products traveling to the Republic of Ireland. In other words, taking sovereignty back over customs controls.

- Quality standards. The protocol forces everything that lands in Northern Ireland to comply with the EU quality standards (CE), regardless of its final destination being in Northern Ireland or the Republic. London now says that if it is only for the northern market, then merchandise could instead be stamped with the British standard (UKCA), significantly lower in most cases. Again, the argument goes: why should subjects of the Queen be exposed to Brussel’s heavy-handed standards?

- Tax cuts. London argues that under the Protocol it cannot offer Northern Ireland’s companies and population the tax deductions it applies to the rest of the UK. This is especially the case regarding the European Union’s VAT, one of the great advantages put forward by the Vote Leave campaign.

- Jurisdiction. Downing Street believes it to be “unfair” that Northern Ireland, de facto part of the single market, should be ruled by decisions taken in Brussels and not by its own autonomous institutions. And, as I mentioned before, the seemingly ultimate humiliation is to be subject to the European Court of Justice (ECJ).

Do these four demands make sense? A certain logic can probably be found for all four if it is sought hard enough. The problem lies with the fact that barely two years ago Johnson, in the name of the UK, signed a legally binding international treaty that he committed to respect. The Brexit deal had been a headache to negotiate for a reason and, undeniably, Boris had run -and won- an election based on “Get Brexit Done”, but he is already “undoing” it.

Imagine Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez sending a letter to Queen Elizabeth saying that Gibraltar’s airport can no longer be used for civil purposes, unilaterally breaking the 2006 bilateral treaty signed by both countries. We cannot imagine it simply because it would be illegal. Or, in the EU Interinstitutional Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič’s words, “legally inconceivable”.

Besides, why would Johnson want to go into the history books as the PM that unashamedly broke international law and endangered British relations with its long-standing allies? Indeed, why would he seek to put more pressure on the fragile equilibrium of the Good Friday Agreement? Ultimately, would the Conservative party and British democracy allow for more of his enfant terrible political extravagance?

Granted, he would not be the first PM to break international law, but 2022 is not Churchill’s era, nor even 2003 when Tony Blair enrolled the UK in an illegal war. There are certain precedents that should be avoided. Moreover, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has turned respect for international law into a rather sensitive issue these days.

So, the question remains: why is Johnson fighting so hard to fight the protocol? The first answer is clear: to stay in the job. Johnson is trying to quell the unrest in his own party by pleasing the hard-Eurosceptic core that grants his survival as Prime Minister. Johnson won the motion of no-confidence by 63 votes (211 vs 148) accounting for 59% of his party peers. Theresa May, who was forced to resign as PM and party leader, won hers by 63% in 2018. The tactic reminds me of my time as a Communication Advisor for the Vice-President of Spain, my boss had written on his wall: “It is the party stupid!” Johnson might be more worried about his survival than about the consequences of his policy decisions, however irresponsible or damaging for his country. He is seemingly scared that people will finally see the clown he loves to be rather than the savior of a leader he struggles to befit.

As part of his dubious plan to remain in Downing Street, Johnson is using the old sentiments of patriotism and British nostalgia for exceptionalism, combined with aspirant Churchillian storytelling in times of war. This has culminated in the harsh diplomatic overreactions to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, specially designed to be shown off during the Queen’s Jubilee celebration, and draconian immigration legislation followed by the suggestion that the UK might abandon the European Convention of Human Rights.

A Trying Time for Northern Ireland

The post-pandemic climate in Northern Ireland has become fragile. Riots and sectarian violence have been sparked largely by the unionist feeling that the protocol is detaching protestants even more from their “homeland”. In a questionable move, unionist leader and Northern Ireland First Minister, Paul Givan, resigned in February 2022 in protest over the protocol and called for elections.

Unification, again, is the talk of the town.

The elections came and, admittedly, a unionist victory in Northern Ireland could have swept the unrest under the rug, with an emboldened DUP working with the Conservatives against the protocol. But Sinn Féin had other plans. By focusing less on identity-religious matters and more on day-to-day issues such as health and social policies, the former political arm of the IRA convinced a majority of Northern Ireland to vote for them for the first time in history. One could only imagine Boris Johnson’s face when the results came in, even if most polls already saw it coming.

Michelle O’Neill, Vice President of Sinn Féin, now has the right to become First Minister of Northern Ireland. And, as the consociational arrangements of the Good Friday Agreement dictate, Jeffrey Donaldson of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), will have to become Deputy First Minister. Predictably, he does not want to take his office until the “Protocol problems” are fixed. Cul-de-sac politics.

This all leaves Johnson with a conundrum: “solving the Protocol problems” will almost certainly involve breaking international law (again) and, more dramatically, feed the monster of a hard border between the two Irelands, whether this boundary is physical or imaginary. The cure might be worse than the disease. And the disease may even worsen if Sinn Féin enters, as some predict, the government coalition in the Republic of Ireland in the next elections. Unification, again, is the talk of the town. Referendum is the elephant in the room. Sinn Fein President and leader of the Irish opposition in the Dáil, Mary Lou McDonald, even recently suggested a time frame for significant change “in the course of this decade.” It does not take an expert to understand the ripples this would have sent through Westminster, but the British PM may already have taken the famous words of Oscar Wilde too much to heart: “Be yourself. Everyone else is taken”.

© IE Insights.