As we emerge from the confines of one of the greatest disruptions in human history, talk of wellbeing is all around us and advancing an age of wellbeing. It is an opportunity, presented by the pandemic, to reflect on where wellbeing comes from and, most importantly, what it means.

Preaching, performance and critical skills: how wellbeing in the workplace has evolved

There is a difference between wellness and wellbeing, although they are commonly used interchangeably. Wellness connotes some element of escape from the day-to-day reality and some notion of ‘fixing.’ Wellbeing, on the other hand, is a more integrated concept within the daily lived experience of human beings, which allows them to be well.

Being well is a simple term which contains much complexity. The human flourishing and positive psychology fields of study consider being well in all aspects of life, with different instruments developed to measure these, at least on a personal subjective level. Physical, mental, social, and financial are some of the main elements, and wellbeing is required in all.

How we view this concept of wellbeing is critical if we are to change the prevailing culture in the workplace that wellbeing is something you do, or look after, on your own time and away from the office. Working culture has often led to imbalance in employees’ lives, and to address this the unsatisfied human needs of workers must be identified. Thus, organizations must be rebuilt to embody wellbeing practices and ideology, rather than being the very thing that workers feel the need to escape from in search of ‘wellness solutions’. Broad acceptance of wellbeing is likewise important in order to scale its impact from being a curious niche towards true mainstreaming.

Yet acceptance of wellbeing as a legitimate business strategy has been stymied by different factors. Firstly, health and wellbeing often suffer from a highly ‘preaching’ tone, admonishing people on their poor choices with the ‘perfect’ teacher shaming students simply by their presence. Of course, credibility and authenticity in such teachers is important. For example, it would not do to have a wellness expert exhort the importance of sleep to a group of executives if she herself appeared exhausted from flying around the world on a weekly basis. But at the same time, it would be impossible to expect someone with a busy schedule to never look and feel tired. We are human after all and thus wellbeing as a business concept must be built on showcasing vulnerability and failure as opposed to our preconceived notions of wellbeing as simply being a vehicle for personal and professional success. It is a journey, not something to be gotten “right” every time.

Wellbeing has been viewed traditionally as a compromise on performance, about doing less work. This led to my focus on sustainable performance as a business case for wellbeing. Work has no finish line and by investing in ones’ own health and wellbeing we can maintain our performance levels in the longer term. Even in the short term, studies show that by investing in areas such as sleep and nutrition, critical thinking, decision making and empathetic leadership are all improved. So rather than doing less work, the performance lens of wellbeing, inspired by the seminal work of the Corporate Athlete, allows us to think about working smarter.

Wellbeing skills include the ability to identify our deeper emotional needs, to design new routines and rituals, to create a new system.

However, in many organizations the pendulum has swung too far the other way. The result has been a whole industry of ‘peak performance’ vendors who use the tools of wellbeing to squeeze even more out of the workforce. Wellbeing may be more present, but if the ultimate intent is simply performance, company culture remains a barrier to a true positive, empathetic, and human organization. There can be residual benefits, but the end result is often a highly engaged workforce that is close to burnout. That situation cannot last, the sustainability of performance must be taken into account.

Wellbeing is a necessary skill – this has become obvious to many during the pandemic in which our working and our non-work lives became blurred. To take a technology analogy, we were forced to find a new operating system in order to manage this new way of working and living. The pandemic has shown that wellbeing skills include the ability to identify our deeper emotional needs, to design new routines and rituals, to create a new system.

It also allows us to be more effective professionals, not quite ‘performance’ per se, but certainly a more mature working human who can add value not only to the enterprise but to our communities (hugely important if we want to re-build a better society post-pandemic). By way of example, wellbeing programs can help leaders by acting as a lens to improve prioritization, relationship building, and developing empathy, among others. The blurred lines of the future world will require us to continually hone such skills.

Going back to the origins: the greatest question in human history?

The field of human flourishing provides a rich context for looking at wellbeing today. With solid academic roots in positive psychology, the definition of human flourishing according to The Harvard Human Flourishing program is “A state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good.”

Though this concept may seem simple to some, it helps unravel the complexity of wellbeing and shows that it does not exist in isolation. Wellbeing is a journey that starts with the self but involves others. Our families, co-workers, neighbors, and every being (indeed every natural element) with whom we share the planet, are all, at some point, part of this journey. Many wellbeing models and definitions, including that of the World Health Organization, make this explicit by highlighting the importance of social wellbeing. And studies show the importance of considering such elements for our own wellbeing. For example, volunteering has been shown to markedly improve mental health. It also leads us to consider that our own health and wellbeing is intrinsically linked to the health and wellbeing of the planet.

This line of inquiry moves wellbeing beyond the workplace. Though the study of wellbeing as a science originates from an examination of life as a whole, the workplace context has helped to accelerate development in the past decade, using the tools of business to gain deeper insights. Given that work is often the cause of reduced health and wellbeing, this has been a critical step. Yet we cannot remain fixated exclusively on the workplace. All life is not work, though work is a significant part of life and cannot be separated from it. The saying if you’re not well at work, you’re not well at home, and if you’re not well at home, you’re not well at work has shown itself to be true time and time again.

Opportunity in disruption: building a wellbeing-based future

There is a need for us all to be involved in shaping the age of wellbeing, through our daily actions and conversations. The pandemic has forced us – perhaps only temporarily – off the hamster wheel of our previous lives. We now have the opportunity to create new ways of behaving.

The corporate world and, particularly, entrepreneurs have a significant role to play in whether a new way of working and living is possible – a world that picks up that question which has been examined throughout human history, beginning with Aristotle: What is a good life? Innovation theory shows that times of great disruption also present huge opportunities, for example the economic crisis of 2007-08 gave rise to modern giants including Uber and Airbnb. What future omnipresent organizations are ‘starting up’ right now? A good number of them will likely address our wellbeing. For example, HealthTech has gained momentum since the pandemic started, with mental health start-ups, such as Ginger, attracting significant interest.

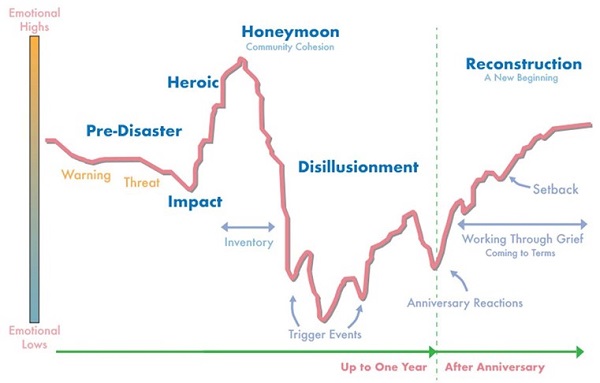

Another academic model that has been cited frequently during the pandemic from Zunin & Myers (below) also shows the work ahead. The model shows an emotional high coming after the impact, which may be surprising, but reflects the positive side of human nature, of working together when confronted with crisis. This, and the subsequent lows (think widespread ‘pandemic fatigue’ starting late 2020) has also been evident in our own shared trauma of the coronavirus. We have experienced a rollercoaster of emotions through the pandemic, and will no doubt continue to do so. Yet by building on the notions of community, what is the new beginning that we can build together?

The current period of reconstruction will be key for preparing for future setbacks. Organizations must focus on improving the day-to-day lives and practices of their workers, focusing on long-term, sustainable improvements rather than PR-driven directives and initiatives. In this new age, notions of wellbeing are integrated in our daily working lives and we are getting ever closer to true human flourishing – of being well in all aspects of our lives.

© IE Insights.