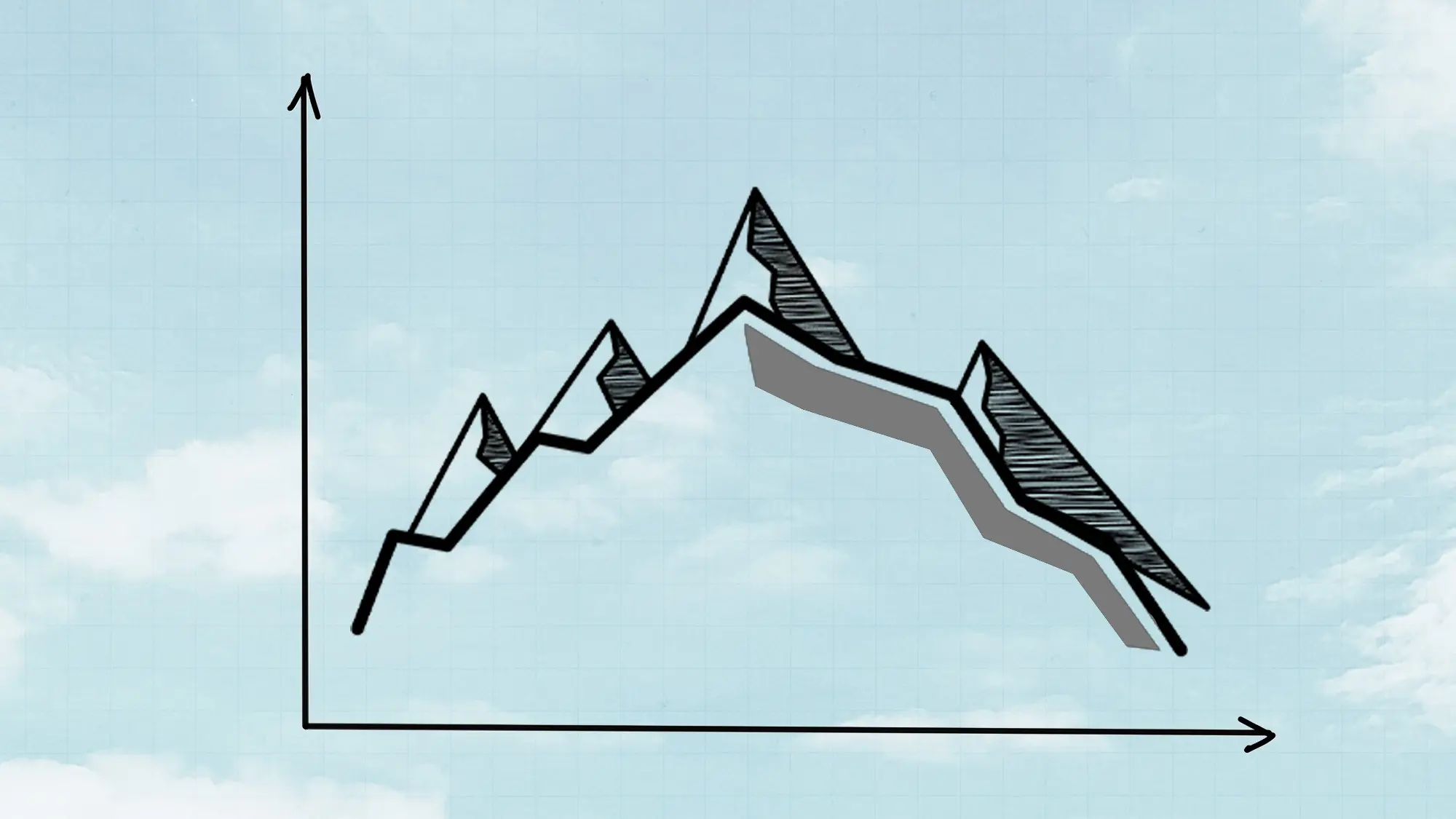

The integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance metrics into executive compensation – often referred to as “ESG Pay” – has quickly become a focal point in corporate governance worldwide. Driven by mounting pressure from regulators, investors, and society, the share of U.S. executives with ESG metrics in their contracts rose from about 15% in 2008 to nearly 45% in 2023, with a marked acceleration after 2018. The figures are even higher among EU firms.

Boards and compensation committees typically introduce these new metrics to align leadership with sustainability goals and long-term value creation. Yet, a closer look at how these incentives actually function tells a more complicated story. My research with Vikas Agarwal and Manish Jha of Georgia State University and Kasra Hosseini of Erasmus University Rotterdam, based on extensive compensation data for more than 5,500 executives across 735 U.S. firms between 2008 and 2023, shows that ESG incentives rarely operate as a simple add-on. Instead, they reshape the incentive landscape itself. In practice, ESG goals don’t merely supplement traditional performance measures – they compete with them for managers’ limited time and costly effort.

For boards, this means that the act of “tacking on” ESG goals without intentionally adjusting the baseline structure of traditional financial incentives risks the perverse effect of diluting managerial focus on core profitability measures. To manage this trade-off effectively, boards must leverage the principles of multitasking theory and prioritize ESG metrics that are measurable, specific, and financially material to the company’s industry. The inclusion of ESG metrics presents an inherent challenge because executives are tasked with achieving both standard financial goals (e.g., earnings before interest and taxes. or total shareholder return) and often less quantifiable ESG objectives. This dynamic is best understood through the lens of multitasking theory, first articulated by economists Bengt Holmström and Paul Milgrom, which shows that when managers face multiple tasks, those tasks inevitably compete for effort, particularly when some are easier to measure or reward than others.

Standard financial metrics in executive pay are generally well-established, measurable indicators that firms have long relied upon. In contrast, ESG objectives are notoriously difficult to quantify, and firms often lack sufficient historical data to objectively calibrate these metrics when setting pay.

A key insight of multitasking theory is that if a task is difficult to measure but value-enhancing (like many ESG objectives are assumed to be), the firm can provide optimal incentives indirectly. It achieves this by reducing the incentives for other tasks that are easier to measure and compete for the manager’s time – in this case, the standard financial tasks. This reduction lowers the “opportunity cost” of the executive dedicating time and effort to the new, less measurable ESG task.

Empirically, our findings strongly support the hypothesis that standard financial tasks and ESG tasks act as substitutes for managerial effort. When firms introduced at least one ESG metric into an executive’s compensation contract, the expected pay-performance sensitivity (or “dollar delta”) of standard financial or accounting metrics decreased significantly.

This reduction is economically meaningful: we find that the average dollar delta of standard metrics in our sample decreases by about $4,600, representing roughly a 20% reduction from the baseline average dollar delta. This means that, for the average executive in our study, the compensation contract is structured so that a 500 basis points (b.p.) increase in the stock price is expected to boost their performance-based compensation by about $100,000. When an ESG metric is introduced, the compensation is intentionally redesigned so that the same 500 b.p. increase yields only $80,000. This reduction in the sensitivity of pay to financial performance is what we mean by rebalancing incentives, indirectly shifting focus and effort away from traditional financial metrics toward the new ESG objective.

Crucially, this observed dilution is unique to ESG incentives. When firms introduce another standard financial metric (which is easily measurable, like the existing metrics), the dollar delta of the existing standard metrics shows no significant change. This highlights the distinctive nature of ESG tasks in the compensation landscape and confirms that standard and ESG tasks are substitutes in the provision of managerial effort.

The evidence also suggests that this structural change reflects efficient incentive design, not managerial rent-seeking. Boards are not simply increasing total pay (total executive compensation remains statistically unchanged) or the power of time-vesting options; instead, they are intentionally reducing the emphasis on easily quantifiable financial tasks to accommodate the harder-to-measure ESG objectives. Furthermore, this reduction in standard incentives appears effective, as it is associated with improved company ESG ratings. Going back to our example, the $20,000 decrease in compensation per 500 b.p. increase in the stock price for the average executive after the introduction of an ESG metric translates into an LSEG ESG rating 0.30 points higher for the firm (the average rating among firms in our sample is 60 points). We find no evidence, however, that this trade-off affects stock prices within the next year, consistent with a long-term price impact of ESG policies.

Practical Implications for Boards and Compensation Committees

The key takeaway for boards and compensation committees is that the incentive trade-off is real, it is significant, and it must therefore be managed proactively. Boards must move beyond boilerplate or symbolic ESG incentives and focus on specific design choices that minimize the competitive strain on managerial effort.

Our research identifies three major leverage points where the design of ESG metrics drastically impact the magnitude of the financial incentive reduction: the number of ESG metrics, their measurability, and their materiality (i.e., complementarity with standard metrics).

1. Avoiding Overload: The Number of Metrics Matters

Overloading an executive with too many performance targets increases their cognitive and effort burden, thereby raising the opportunity cost of putting effort into standard financial tasks.

Our results show a non-linear effect (convex relationship) between the number of ESG metrics and the reduction in financial incentives, suggesting that “less is often more.”

- Introducing a single ESG metric yields a modest and statistically weaker reduction in the dollar delta.

- When two or three ESG metrics are included, the average reduction in the dollar delta accelerates to about $7,200.

- With four or more ESG metrics, the drop becomes even more pronounced, decreasing by approximately $8,400.

Boards should be wary of accumulating multiple, disparate ESG metrics simply to satisfy various stakeholder groups. If the board is serious about ESG goals, this tendency toward metric inflation should drastically weaken the core financial incentives meant to drive shareholder value.

2. Prioritizing Measurability: Minimizing Uncertainty

The theoretical reason for the incentive trade-off is the difficulty in measuring ESG effort relative to financial effort. If an ESG target were as quantifiable as, say, EBIT, the executive could be held directly accountable without diluting incentives for traditional financial tasks.

Boards must define ESG metrics with explicit, quantifiable criteria to minimize the dilution effect:

- Non-Measurable Metrics: The addition of a non-measurable ESG metric – one lacking explicit benchmarks (minimum, threshold, or maximum performance triggers) and clearly reported payouts – causes a statistically significant decline in the dollar delta of standard metrics, averaging $1,769 per metric. Examples of such ambiguous metrics might include “Progress toward our long-term sustainability goals.”

- Measurable Metrics: When the new ESG metric is measurable (e.g., “Cumulative Carbon Emissions Reduction” where vesting benchmarks are explicitly defined), the change in the dollar delta of standard metrics is statistically indistinguishable from zero.

For compensation committees, this means that poorly specified or overly flexible ESG goals – which some literature suggests may be vulnerable to managerial manipulation or discretionary payout adjustments – are the ones that impose the heaviest opportunity cost on financial performance focus.

3. Aligning with Materiality: Fostering Complementarity

Materiality – whether an ESG issue is financially significant enough in a given industry to affect a firm’s performance, risk, or long-term value – is a critical factor for managing the effort trade-off. Financially material ESG tasks are generally more complementary to standard business objectives, meaning that effort put into one task may decrease the marginal cost of effort for the other.

Boards should leverage frameworks like the SASB Materiality Index to select performance indicators:

- If an ESG metric is financially material to the executive’s industry, the decrease in the dollar delta of standard metrics is statistically indistinguishable from zero. This suggests that directing executive effort toward material ESG goals (such as water management for a utility company) minimizes the substitution effect because these goals are viewed as mutually supportive or intertwined with long-term financial success.

- In contrast, if the metric is non-material (and thus less complementary), the incentive trade-off becomes economically and statistically significant, resulting in a reduction of $1,067.3 in the dollar delta per non-material metric added.

For boards, intentional design requires selecting ESG goals that are core to the firm’s financial risk and value-creation strategy, rather than adopting generic or non-material goals for broad compliance purposes.

Navigating the Incentive Landscape: A Strategic Roadmap

The data confirms that firms are actively, and often symmetrically, managing this substitution effect: the dollar delta of standard financial metrics declines when ESG metrics are added and, conversely, increases when those metrics are removed. This pattern reflects executives’ rational allocation of effort in response to the incentives placed before them.

To transition from merely “tacking on” ESG incentives to designing compensation systems that genuinely shape behavior, compensation committees should implement a strategic roadmap focused on specificity, quantification, and alignment with financial materiality.

When boards fail to engage in this deliberate recalibration, they risk creating a compensation structure in which executives, facing limited time, respond to poorly designed, non-material ESG incentives by ignoring them. By contrast, prioritizing ESG metrics that are measurable, financially material, and limited in number enables boards to integrate sustainability goals that genuinely complement (or at least minimally compete with) the core financial mandate. This approach yields a more efficient allocation of managerial effort that ultimately leads to stronger ESG performance.

© IE Insights.