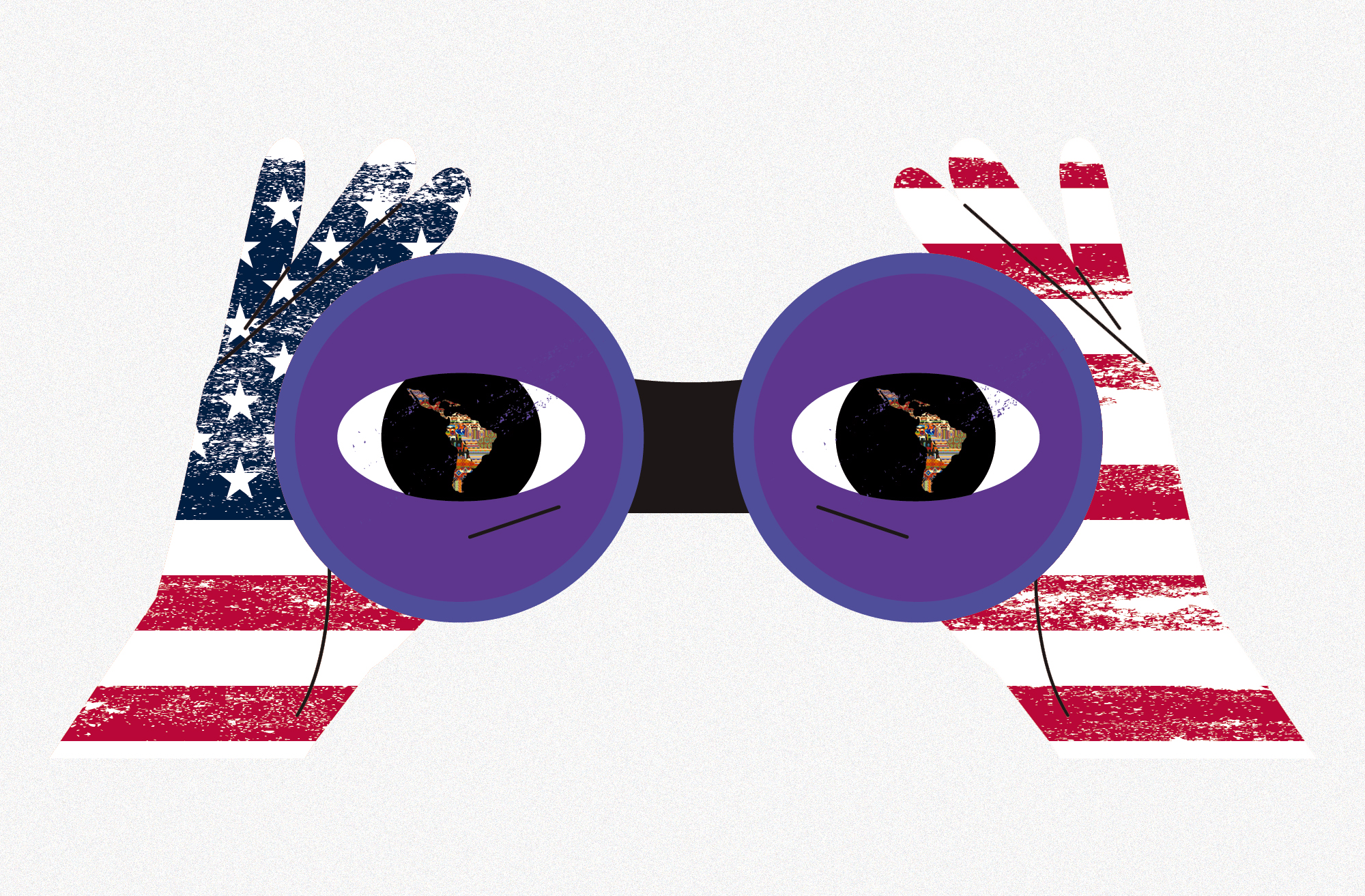

US diplomacy is hard at work – perhaps more so than in the last three decades – managing the various challenges on the global chessboard. There is the issue of how to manage relations with the new China and the leadership of an assertive Xi Jinping, while tracking the invasion of Putin’s Russia on Ukraine and Europe. Within this present scenario, Latin America might not seem to be a priority for US foreign policy… status quo, really, since the end of the Cold War.

Indeed, the period of relative calm in the geopolitical sphere after the fall of the Berlin Wall brought waning interest in Latin American affairs. However, there are now small signs that Washington would like to strengthen relations with its continental neighbors and regain influence in the region.

Against a backdrop of growing tension and fragmentation, Ibero-American states, from Mexico to Argentina, could prove to be strategically valuable in terms of their role as reliable trading partners and their diplomatic and political support in a turbulent international scenario.

China is advancing slowly but surely in its trade and diplomatic operations in Latin America.

China grasped the importance of the region more than two decades ago and has been forging ahead, building and strengthening a network of trade and investment-based relations with the region’s leading nations in strategic sectors including natural resources and key infrastructure such as ports and electricity generation and distribution. This strategy has made China South America’s main partner, though at regional level the USA remains dominant thanks to its interests in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

China’s capital stock in the region has grown significantly in recent years to US$629 billion, and currently accounts for 18% of Latin America’s inbound investment. Its flagship program, the Belt and Road Initiative, continues to garner influence in the sub-continent and added a new regional partner to its portfolio last February. The signature of President Alberto Fernandez, following Chinese pledges of US$24 billion in investments and loans, made Argentina the 20th country in the region to join Xi Jinping’s project.

This process has gone hand in hand with an increase in state visits by Ibero-American leaders to Beijing, deployment of the state-run Xinhua news agency throughout the hemisphere, increased outreach of CGNT’s Spanish-language channel, and the withdrawal of the recognition of Taiwan by countries such as Panama in 2017, Nicaragua in 2021, and the increasing likelihood of Paraguay changing its alliances to the People’s Republic of China.

There is a struggle for influence in Latin America.

There may be some change noted on the political radar of the State Department in Washington, due to the new geopolitical reality and the growing fear of further Chinese infiltration in the Latin American economy. For example, the US government’s push to appoint Mauricio Claver-Carone as the President of the Inter-American Development Bank – a break from the unwritten rule of leaving the presidency of the institution to a Latin American – was not just another Trump-led ploy. In all probability, Washington wanted to increase its control of this important multilateral bank at a time when other actors are emerging in the region, such as the NBD, the BRICS bank headed by the Brazilian Marcos Troyjo though based in Shanghai, and other Chinese state banks such as the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China, and the Industry and Commerce Bank of China are approving loans for large projects.

The relaunch of the Summit of the Americas with the celebration of the 9th Summit in Los Angeles was another move that highlights the United States’ interest in regaining ground in Ibero-America. On this occasion, Joe Biden personally hosted the Latin American leaders, at least those who attended. This was a significant shift compared to the absence of Trump from the previous summit in Lima and underlined the new president’s increased sensitivity to his southern neighbors. It was an opportunity to showcase a new regional agenda, in which President Biden aimed to link the advancement of rights and democracy to regional prosperity.

The result was not particularly impressive, though this was to be expected insofar as the United States, in its role as the world’s leading democratic power, is required to include issues such as human rights and democracy on the agenda of any dialogue and agreement (compared with China which, except for accepting its vision on the Taiwan issue, hardly ever imposes conditions on its partners.)

The enormous political capital that the US had built up in Latin America has been seriously eroded over the years.

The United States’ rapprochement with Latin America has been slowly moving forward through new initiatives in the region. In July, the United States, Costa Rica, Panama, and the Dominican Republic signed a memorandum of understanding to create the Alliance for Development in Democracy that seeks to develop supply chains and economic growth between the United States and these countries to foster a model of cooperative innovation among like-minded democratic nations, and improve the lives of their citizens and the people of the region as a whole. This is a way to develop trade links with southern neighbors in a world in which globalization is moving towards regionalization, also known as nearshoring or friend shoring.

The search for ways to ease the embargo on Venezuela, whose oil is more strategic than ever after the sanctions imposed on Iran and Russia, is yet another sign of change. Anthony Blinken’s recent visit to Colombia to meet Gustavo Petro, during which the US showed a more receptive attitude to relations with Venezuela and the fight against drugs, could also be indicative of Washington’s growing interest in winning the hearts and minds of the 22 Ibero-American countries and their 700 million citizens.

Constraints impede on US foreign actions.

This will not be an easy task. The enormous political capital that the US had built up in Latin America has been seriously eroded over the years, especially since Trump’s term in office, according to the surveys conducted periodically by the analytics and advisory firm Gallup. This is hardly surprising given the declarations made by the previous tenant of the White House about the region and immigration.

In the 2018 survey, US leadership in the region was ranked on a level with that of China. It seems that the discreet work of Xinhua, CGTN and the not-so-low-key missions and official visits announcing investments, loans and procurement, conveniently reported by media sources, have succeeded in creating an image of China as a responsible, reliable partner in the region’s collective psyche.

However, this image only refers to the country in terms of its influence as a superpower. The dream of Latin American economic immigrants, and also of its elite, is still very much “American,” with the United States being seen as a country of freedom and opportunities, embodied in the migration of the poorest to the north, and in the luxury apartments in Miami, to which a large part of the sub-continent’s population still aspires. A dream which, in all probability, few associate with the People’s Republic of China. This continues to be the major asset of the United States.

State control of the media, of large foreign and credit banks and, indirectly, of private companies, has given China the power to push forward consistently and quickly, when necessary. This is especially true given that it is a state with enormous resources whose power is increasingly concentrated in one person.

None of this is an option in the United States, where the State is managed by a democratic regime that is ultimately chosen in elections and must therefore be accountable to its citizens. This is an even greater weakness in situations of extreme polarization such as the current climate in the world’s most powerful country. A case in point is the fact that there was even question over whether there would be economic backing for Ukraine in the war against Russia if the Republicans won the mid-term elections.

The US federal government has the most powerful army in the world, but it has fewer resources, and less control over those resources, to deploy in other foreign actions in areas such as finance, information and aid, given that the world’s most powerful liberal democracy has traditionally delegated these areas to the private sector.

The public Eximbank and the USAID agency not only have fewer resources than their Chinese counterparts, but they also have more complex internal processes, as befits a democracy, which imply greater requirements in terms of transparency and compliance, both internally and with their partners. The same is true of other institutions such as the legendary Voice of America, the US public foreign information service, whose influence pales in comparison to the services of China and Russia, and even of European services such as the BBC, whose Spanish-language content on bbcmundo.com is shared by hundreds of online newspapers throughout Latin America, and the state-run France24, which has opened television studios in Bogota.

Although the American CNN is probably one of the most recognized news sources in the region, through CNN International, CNN en Español and its local branches in Brazil and Chile, its ultimate goal as a private media company is to make profits and be truthful which, in many cases, includes broadcasting the USA’s domestic contradictions to the rest of the continent.

The Monroe Doctrine, “America for the Americans”, had been gathering dust since the US became the world’s sole superpower. Yet at a time when China has made it clear that it aspires to stand on a par with the USA, James Monroe’s idea is once again being bandied about in US offices. However, on this occasion, US diplomacy would do well to learn from the practices that China has deployed in the region, given the negative connotations that the name Monroe left in Ibero-America during the Cold War period.

This article originally ran in Spanish in Foreign Affairs Latinoamérica.

© IE Insights.