During the Middle Ages, the sculpted and painted images on churches and monuments served as a form of education, predominantly religious, and as the foundation for the cultural life of the community. It is therefore interesting to consider how it was possible for the Medieval viewer – 90% of whom were illiterate – to understand this iconography. This question can likewise apply to today’s public who visit these same buildings, for while modern society represents an inverse change of that illiteracy rate, medieval iconography is no less elusive.

We must first ask ourselves what elements could facilitate the reading of the iconography by a person who lacked the necessary knowledge to do so and for this it’s important to consider the social and cultural background of the 10th – 15th century and also the key components of the language of images.

Since the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century and during those that followed, Europe experienced a progressive change in all its structures. By the year 1000, the feudal system was fully formed and characterized by a strict hierarchy that affected the entire social body. Some individuals depended on others who had the capacity to fully own the means of economic production. The structure of the state and the law were also affected, and this led to total confusion about what was public or private. For example, a count, who originally represented the king’s public authority in a certain territory could exercise power and receive taxes as if that land belonged to his own family.

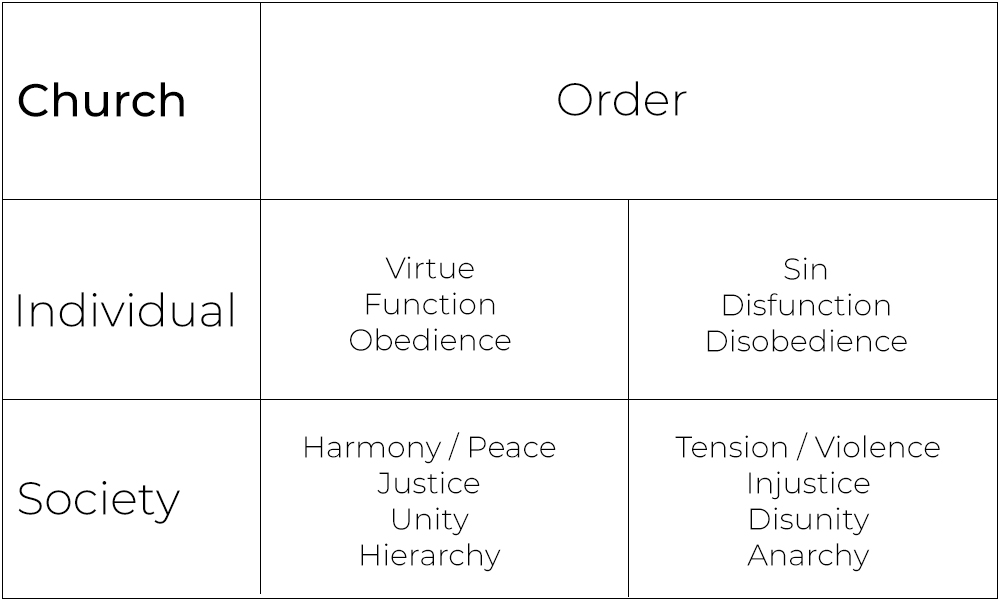

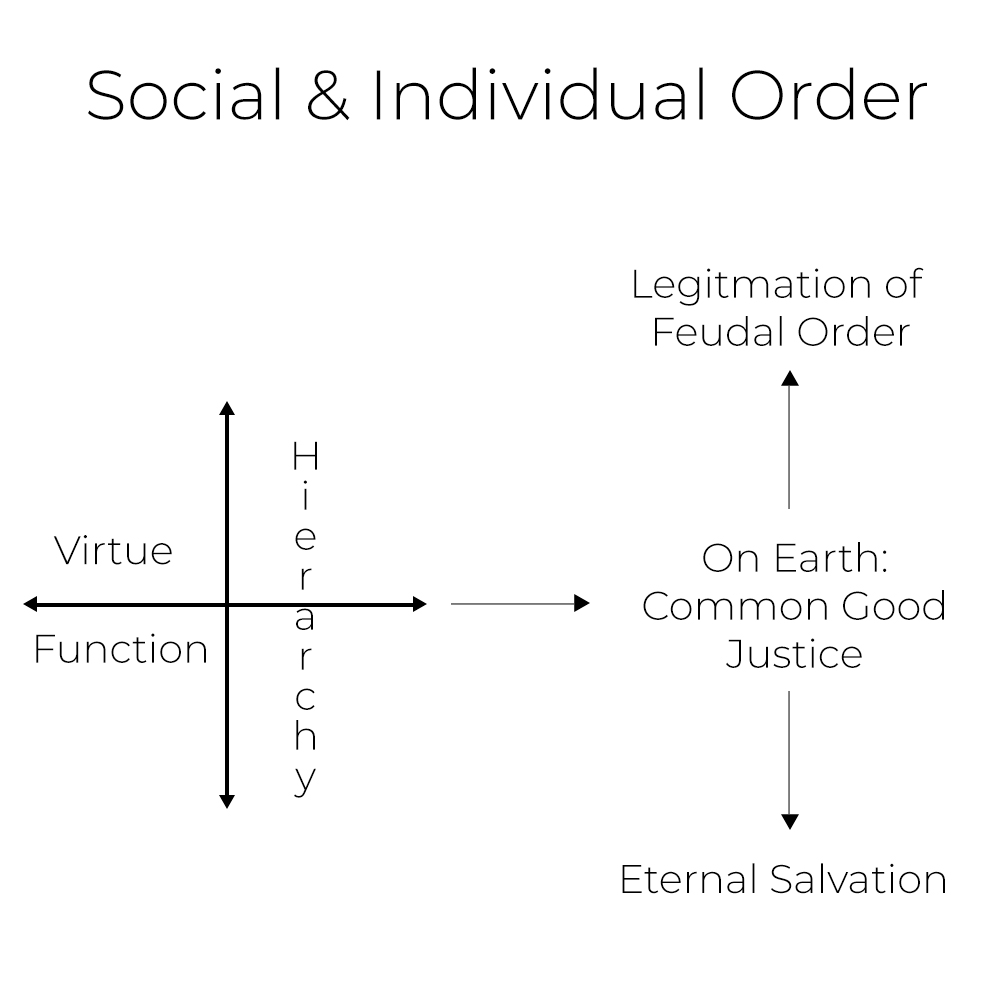

Finally, we can affirm that the culture of the feudal system was dominated by the Church, which promoted order as a central concept of the common and individual functioning of society – thus Order was a core value for feudal Christian Europe. Using the terminology of sociologist Max Weber, we can see order as a rationality, a concept that provides meaning and articulates a set of essential values for a society.

In the Western Medieval mentality, there was an individual order, made up of a set of Christian virtues that applied to the social function that each individual must fulfill, from the king to the base of the pyramid through the different social strata. Those states could be three (priests, warriors, and peasants, who were identified with the Holy Trinity, according to the symbolic tripartite social theory), or 39, as listed by Jacques de Vitry, one of the best-known preachers of the Medieval period. The number varied depending on the time period or author, but the underlying concept of order remained constant. For those who occupy the base of the social body, obedience and humility were the fundamental norms, the basis on which the relationships of a strongly hierarchical society were articulated. Meanwhile, for the privileged, those who held a dominant position, moderation in the exercise of power was the key element.

The Three States, 13th Century (British Library. Ms Sloane 2453)

On the other hand, we must consider a social order, based on four elements: peace, justice, unity, and hierarchy, which should provide the necessary framework for achieving the common good.

The Church’s social doctrine affected both the individual and society. It was not a Medieval creation but an adaptation of the social and political principles of the Roman civilization. Of course, we are talking about a theoretical and regularly breached model. It is up for debate as to whether it was universally shared or to what extent it was contested. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that this was a model to which the Christian Church aspired for common good and had the ultimate goal of eternal salvation for the whole society. At the same time it became an effective way of legitimizing the hierarchical system.

This is represented below, including the elements that make up the concept of order but also the antagonists that can destroy it:

The analysis of narrative technique is not usually applied in Medieval iconography studies, but this methodology can help us uncover what an illiterate viewer understood when facing that world of images and symbols.

It would be difficult to find someone today who has not read a novel or watched a movie. Maybe we are not aware of it, but the sequencing of the scenes, the way in which the author presents and interconnects them is what makes the narrative intelligible, so that the reader or viewer can navigate through the story and understand it. This is called narrative time. As Stephanie Nelson of Boston University and Barry Spence of the University of Massachusetts Amherst detail, “Time is an inherent, constitutive aspect of narrative, whether the narrative concerns fiction or not.”

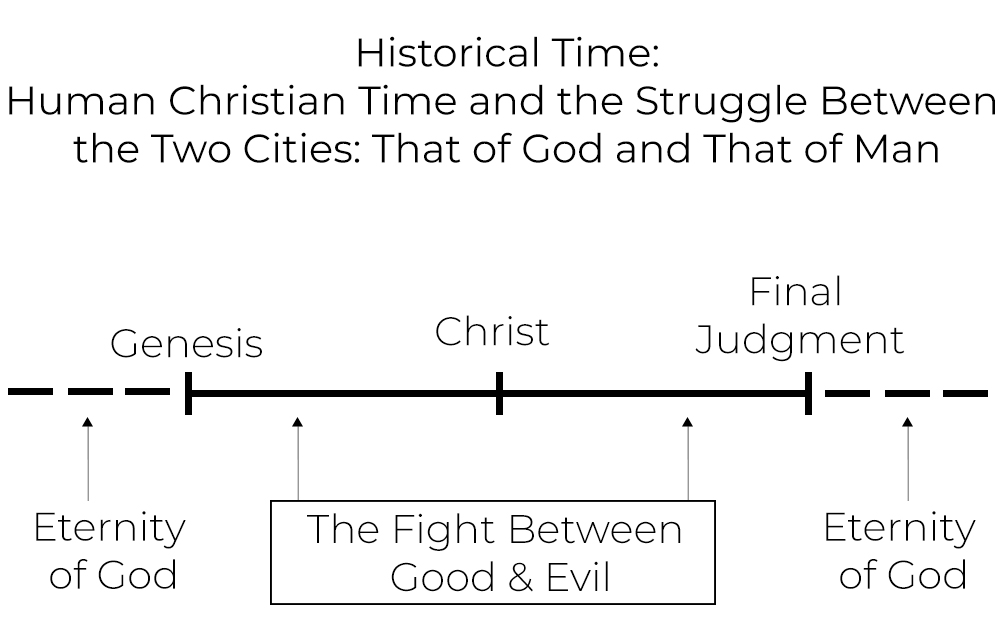

After generations of Church indoctrination, any Medieval spectator had in mind an already constructed time, which included both the real and fantastic protagonists of the temple. This mental construction is “human time” and, in Christian mentality, has a very precise definition: it was created by God, it will have an end, and the life of Christ is a milestone within this timeframe. Human time is preceded and succeeded by the Eternity of God and during this earthly existence, a never-ending battle is fought between good and evil, as St Augustine describes in his major work, The City of God. This is the story of the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, which we can represent graphically like this:

The protagonists of the visualized scenes were placed over that imaginary construction that every Medieval Christian had in mind. Preaching helped build that idea.

In addition, the language of these images is a canonical set that, in general terms, is represented in a similar way anywhere throughout the Western Christian space, whether in France or England, the Iberian Peninsula, Germany or Italy. It is a universally represented corpus, made up of models with similar characteristics, although executed with unequal quality here and there.

The evocative power and the ability to stay in memory are reinforced through agent images. The imago agens, in Latin, is in the terminology of classical ars memoriae (the Art of Memory), a mnemonic tool effective in its ability to provoke an emotional response. The viewer remembers it because of its shocking qualities: an extraordinary beauty or ugliness, violence, distortion, comedy, or pathos. It is this emotive extravagance of the images that makes them ideal support to symbolize (which is one of their essential features), to narrate, to memorize, and to facilitate their recovery.

Let’s consider a well-known artistic example: the Romanesque cathedral of St Lazarus of Autun, in French Burgundy.

Cathedral of Saint Lazarus of Autun, Main Door

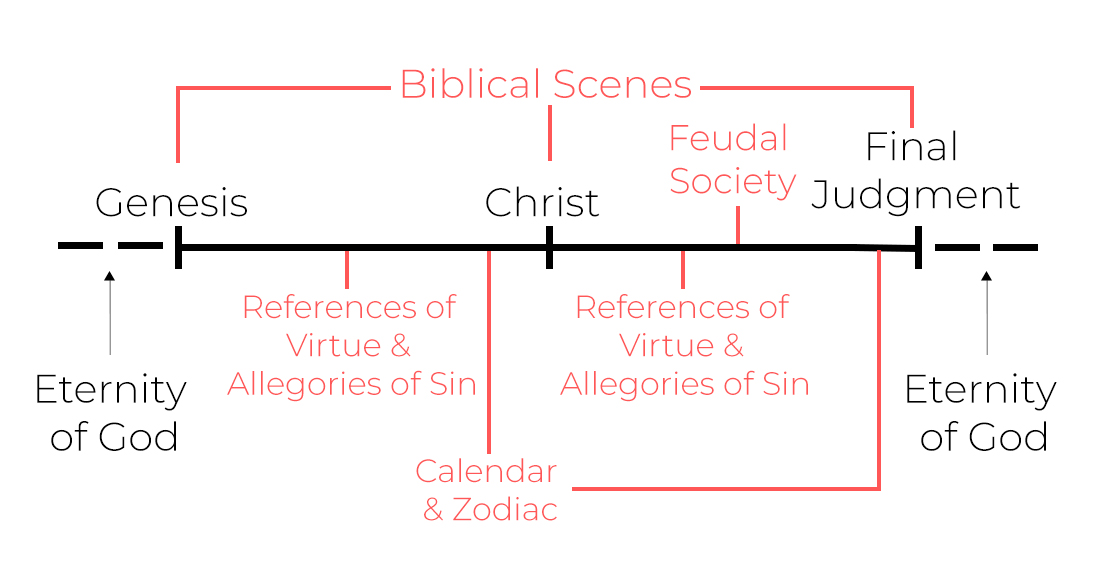

On its main façade and interior, this 12th-century temple contains hundreds of carved images whose themes can be systematized as follows:

- Biblical scenes: Among others, Cain and Abel, Noah, Samson, Moses, Daniel, Christ, Last Judgment, and the Devil. We must understand that the Medieval viewer does not regard these scenes as simple literature but as precise historical references that talk about Good and Evil, salvation, or damnation.

- References of virtue: Prophets, apostles, saints, historical figures such as Emperor Constantine the Great.

- Allegories of sin (greed, lust, violence): Mermaids, fauns, monsters, combats.

- Feudal society: Peasants, warriors.

- Calendar: A representation of the months of the year, and the Zodiac in which the earthly Order and the celestial Order of the planets and constellations are put in parallel.

The Medieval individual would make a mental construction of all of this with the themes projected as follows:

This method can essentially be applied to interpret any Medieval monument or artistic work. Thanks to the social and cultural background in which Medieval illiterate viewers lived and to the components of the language of images, this is how they – and any viewer to this day – could understand that world of images. Furthermore, it was an effective pedagogical tool. The images were very effective in educating in basic Christian values and principles and were combined with preaching to arouse emotions and capture biblical teachings. According to Platonic theories, knowledge and faith penetrated the mind through the senses, fundamentally through sight and hearing. Sunday after Sunday, generation after generation, illiterate people were able to understand, assimilate, and remember the foundations of the individual and social order on which the functioning of feudal society was based.

© IE Insights.