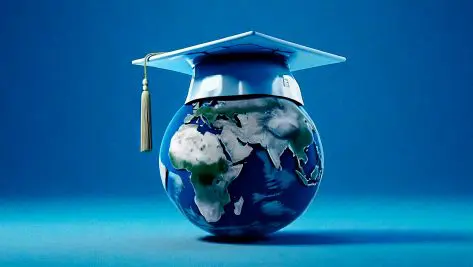

In many parts of the world, academic freedom is under pressure, if not openly attacked. This is happening in authoritarian regimes, but also in democracies that are gradually becoming more rigid. At the same time, universities are now central to how societies respond to technological, political, and social change. In this context, universities are returning to what they have always been in times of crisis: institutions that are decisive for the future of societies. Not only because they train human capital and produce scientific knowledge, but because they are drivers of social mobility, innovation, public debate, and, in general, collective trust.

This is not an abstract statement. It is a structural fact of our time. The 21st century is the century of the university. For the first time in human history, a significant portion of the world’s population has access to tertiary education. In advanced countries, almost one in two young people has a university degree; globally, the percentage is growing rapidly. This is a profound transformation, comparable in impact to the mass literacy of the 20th century, the century of schooling. And as then, the consequences are not only economic, but political and civic.

Universities are no longer – if they ever really were – ivory towers. They are large social infrastructures. They produce skills, of course, but also networks, common languages, and norms of cooperation. They create the conditions for complex societies to function. Where universities are strong, open, and credible, a country’s ability to cope with difficult transitions – technological, demographic, environmental – increases. Where universities are weakened, delegitimized, or isolated, the quality of democratic life is also slowly eroded.

However, there is one point we cannot avoid. Precisely because universities matter more, their role has grown more controversial. In many political contexts, they are described as separate, self-referential places, distant from “real life” – seen as elitist enclaves that speak mainly to themselves, concentrated in large global cities and disconnected from the rest of the country. This is a dangerous narrative, but it does not come out of nowhere. It reflects perceptions that universities themselves must address.

European universities are, historically and geographically, anchored to cities, increasingly global ones. They are central hubs of urban life: they attract young people, talent, investment, and culture. Milan and Paris, Berlin and Amsterdam, Madrid and Barcelona are clear examples of this symbiotic relationship. But this strength also generates resistance. If, in the collective imagination, the university coincides only with the dynamic and successful urban center, it risks becoming invisible – or worse, hostile – to those who live outside those circles. The result is a divide that is not only territorial, but social and political.

Universities remain one of the few places where dissent can be practiced without turning into mutual delegitimization.

The issue is not one of communication, but of substance. Universities have a duty to demonstrate, in practice, that they are institutions at the service of society as a whole. This means expanding opportunities alongside excellence, making research understandable, accessible, and useful, and contributing not only to advanced companies but also to public policy, schools, and democratic debate.

This is particularly true in Europe, where the major transitions underway – digital, green, demographic – are putting social trust under stress. Without shared knowledge, without widespread skills, without credible places of mediation between knowledge and public decision-making, societies become polarized. And when polarization grows, universities become an easy target: symbols of an elite to be attacked, rather than common resources to be strengthened.

And yet, if we look at the data, universities are the primary vector of social mobility today. In systems where access is truly open and supported by policies on the right to education, universities continue to be one of the few functioning social elevators. They are not perfect and not enough on their own, but without inclusive universities, inequalities become hereditary. The real alternative is not between elite universities and mass universities: it is between open institutions and closed ones, between systems that take responsibility for access and those that leave it to chance.

There is also another element that is often underestimated in public debate: the role of universities as places of civic education, even when they do not explicitly state this. Campuses are spaces for intensive socialization. It is there that fundamental skills for democratic life are learned – or not learned: cooperation, trust, conflict management, and dealing with differences. These are not incidental “soft skills.” They are social and emotional skills, structural civic abilities, without which complex societies cease to function.

In a world marked by information fragmentation and the radicalization of public discourse, universities remain one of the few places where dissent can be practiced without turning into mutual delegitimization. Where method matters as much as opinion. Where empirical evidence still has a place. Defending academic freedom means defending this possibility. It also means actively exercising it, not taking it for granted.

This is why universities must move away from a defensive mindset. It is not enough to react to attacks; isolation must be prevented. We must reconnect beyond the physical and symbolic boundaries of cities. We must strengthen our ties with local areas, schools, and institutions, and invest more seriously in the dissemination of research, without trivializing it but also without hiding it behind the language of experts. Impact cannot be measured only by rankings and citations; it must also include influence on the quality of democratic life.

This requires strategic choices. It requires treating the university as a national and European infrastructure, not as the sum of particular interests. It requires public policies that truly place higher education and research at the center of development, rather than considering them an expense to be contained. But it also requires universities that are capable of critically questioning their own role, their own language, and their own practices of inclusion.

In the 21st century, the success of universities will not be measured solely by their ability to produce technological innovation or economic growth. It will be measured by their ability to hold together increasingly diverse, long-lived, and mobile societies. They must strengthen confidence in a shared future, at a time when the temptation to close ourselves off is strong. Universities are more important than ever. Precisely for this reason, they cannot afford to be perceived as distant. They must be authoritative, not self-referential. Open, not besieged. Rooted, but capable of speaking to the world.

The future of universities will be decided not only on campuses but in how societies choose to engage with knowledge. It is a political challenge, even more than an academic one. And it concerns everyone.

© IE Insights.