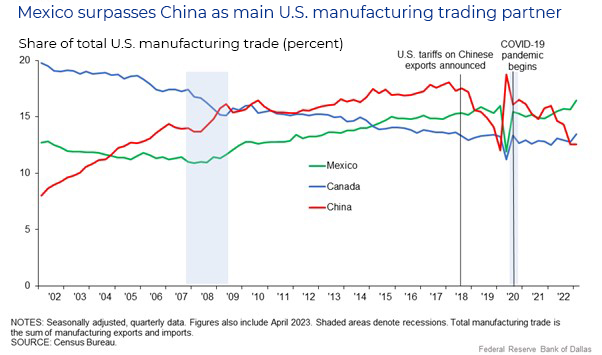

Data released last week from the US Department of Commerce showed that Mexico surpassed China in 2023 to become the leading trade partner of the United States. While Mexico’s exports to the US market rose by 4.6%, Chinese exports plummeted by 20% over the previous year, putting Mexico in first place.

What was surprising about the news was not that it did happen, but that it took 30 years to occur after the signing of the 1994 NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), replaced by the USMCA in 2020. Mexico enjoyed the advantages of immediate geographic proximity, low costs, close diplomatic ties, and near-zero tariffs on its exports to the other NAFTA members, the United States and Canada, and it seemed a natural and complementary trade partner. The peso crisis that hit Mexico shortly after the NAFTA signing was a setback, as was the 2000-2002 crisis and the Great Recession, yet there had been plenty of years for the dynamic Mexican economy to recover and soar to first place.

But in 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). A combination of very low Chinese wages and prices, the manipulation of China’s currency to make its exports very attractive, and technological advances that reduced ocean shipping costs meant that China was able to shoulder its way past Mexico in 2004-2006 and become the biggest trade partner of the United States.

In a sense, it could be said that China’s explosive entry on the global trade scene stole Mexico’s promise. The hope of NAFTA was that as Mexico began to exercise its comparative advantage in manufacturing, it would not only become the key US trading partner, but wages and employment would rise in Mexico in the sectors that were engaged in NAFTA trade. Though wages and employment in the same sectors were predicted to fall in the United States, economists expected that US consumers would be compensated with the lower-priced goods that Mexico would begin to produce.

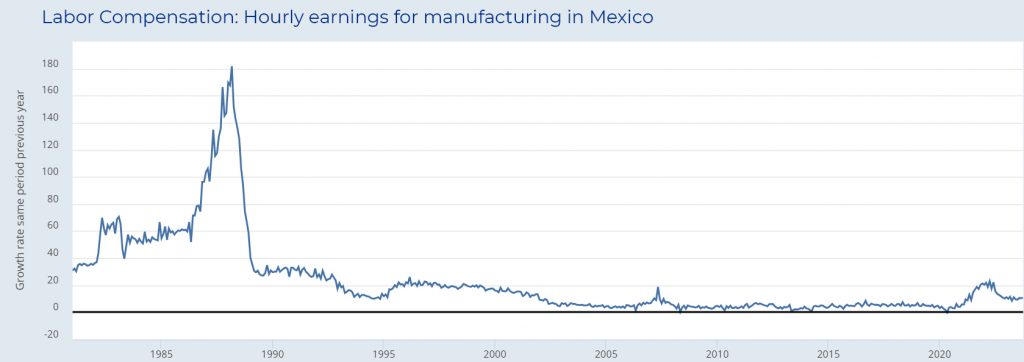

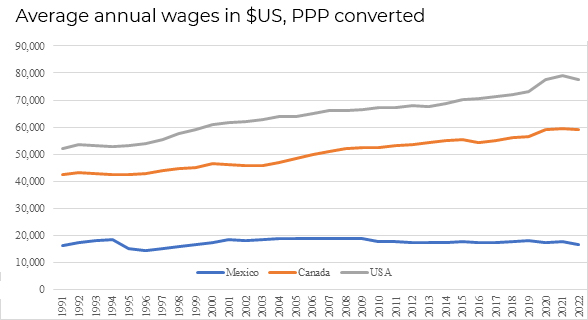

Thirty years later, little has turned out as expected. Mexican wages overall, adjusted for inflation, have barely risen since the NAFTA and USMCA treaties were signed. Part of the explanation is that NAFTA-related production is a relatively small part of the Mexican economy. Another is that the high degree of informality in the Mexican labor market has kept workers from benefiting fully. Excess profits by company owners on both sides of the border is another possible cause. One major analysis of the issue concluded, “while NAFTA has had a small positive effect on urban wages in Mexico, it has not been sufficiently powerful to offset other forces that keep labor earnings low.” But a compelling reason for stagnant Mexican wages is that products made by even lower-wage Chinese workers displaced potential Mexican exports to the US market for years, squeezing out the expected benefits for Mexico and holding Mexican incomes largely stagnant.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

What is it that finally brought Mexico to the fore as the main US trading partner in 2023 (and main manufacturing trade partner since 2022)? There are three main forces, only one of them economic, which broke the trend of ever-rising Chinese exports and may keep Mexico in first place for the foreseeable future.

The first is geopolitics. Former US president Donald Trump launched a trade war in 2018 with a special focus on China, which turned out to be politically popular. He slapped tariffs on nearly 67% of China’s exports to the US market, and President Joe Biden has not reduced them. The animosity toward China was aggravated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the perception that China sided with the invader. Currently, the average US tariff on Chinese imports is 19.3%, slightly lower than China’s average tariff on its imports from the US (21.2%), but much higher than the average tariff levied on imports among WTO members, which is 9%. (The average US tariff on Mexican goods is only 0.2%.)

Regardless of who wins the 2024 presidential election in the United States, these tariffs are unlikely to come down by much. Trump has threatened tariffs of up to 60% on Chinese imports, and President Biden is considering new levies on China’s electric cars, some semiconductors, and inputs to solar energy products.

Of course, the global pandemic that started in 2020 marked a before and after in US-China trade relations. The severing of supply chains and the skyrocketing price of shipping (the Shanghai shipping cost index was six times higher in February 2022 than it was pre-Covid) disrupted prevailing trade patterns and exposed the vulnerabilities of building business around far-flung global supply chains. When China locked down with its destructive “zero-Covid” policy, trade was once again frozen. Many Western companies therefore turned to other trade partners, and the trends toward “near-shoring” or “friendshoring” in trade and investment appeared to gather momentum.

Chinese companies have had to find ways to thrive in this new environment, and one of their responses has been “transshipment”: exporting Chinese goods to Mexico and then re-exporting them from there to the United States, to bypass the tariffs. This practice is closely watched under the NAFTA/USMCA treaties, but recent data on the number of Chinese containers going to Mexico – a 28% increase over the past year – show that widespread transshipment may be occurring. If this were the case, paradoxically China might in fact still be the main US trading partner.

Chinese companies also have a second option: to invest directly in Mexico with the intention of producing there for export to the US market. The United States traditionally accounts for about half of all foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to Mexico, with half of that going to the manufacturing sector. China has represented only about 1% of all FDI into Mexico. Though data is difficult to obtain, some sources indicate that Chinese foreign investment in Mexico has risen substantially since 2018 and is concentrated in goods for export to the US market: electronics, cars, home appliances, and services. Data on total FDI to Mexico, however, does not yet show this surge: between the time NAFTA was signed and 2022, FDI flows from all countries to Mexico has usually remained in the range of 2-3% of Mexican GDP. If China is in fact pouring money into Mexican investments to be able to sidestep the tariffs and export to the United States, this could become a new source of tension with the US government.

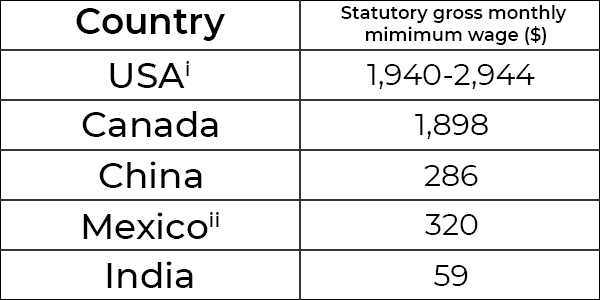

But the main economic change is that Chinese wages have climbed with fast GDP growth, and this has made its exports less competitive. Recent figures from one source show that the average monthly wage in manufacturing in China has risen to $840, compared to only $480 in Mexico; another says the average hourly figures are $6.50 and $4.82, respectively (compared to some $25/hour in the United States). The table below shows the difference in monthly legal minimum wages. Mexico’s wage moderation may have made it a lower-wage manufacturer than China, increasing its competitiveness.

Source: Wage Indicator

[i][ii]US and Mexican monthly minimum wages are calculated as daily legal minimum wage times 5 days times 4.33 weeks per month. In the United States, the minimum wage ranges from $7.25 per hour to $16 in California and $17 in Washington D.C.

How will Mexico’s ascendancy affect its USMCA trade partners, and the world? On the negative side, if the turn toward Mexican rather than Chinese exports is due to animosity or tariffs, US firms and consumers are paying a higher price than before, which is a net loss for them. On the positive side, more trade between close neighbors is good news for the environment, as it reduces emissions from shipping.

On a deeper level, the prevailing thinking about trade and globalization may be shifting away from purely economic concerns to bigger questions about climate, the resilience of supply chains, and even national security. In all of these aspects, more trade with Mexico is better news. Possibly the shift may even presage a trend toward closer integration among the nations of the Americas, who have long been natural trade partners but have been slow to realize their potential. More trade and greater investment in manufacturing or services by Canada, the United States or Mexico in their American partners to the south would benefit all sides and help address the politically charged problems of poverty and immigration.

It has been a long time coming. But, if after its slow climb upward, Mexico retains its position as the main US trading partner, this bodes well for the future of all parties, and for the American continents. A more integrated North and South America, with their natural affinities, has itself been a long time coming, and if it becomes reality, it will present many future opportunities for both continents.

© IE Insights.