The global order is undergoing fundamental transformation, with shifts in alignments and priorities on areas as crucial as trade, security and international development. While we have largely processed the populist sentiment that has accompanied both of Trump’s terms in office, what is coming into sharper focus is the degree to which oligopolistic influence now dominates our economic and political environments. Many of us – policymakers, investors, and analysts in established economies – have been slow to confront the systemic risks this concentration poses.

Within any nation, a concentration of wealth and influence comes with increased risks of all kinds. While it may be easy enough to paint America with that particular brush, a similar picture forms when looking at it from a global perspective. The goal of any resilient system is to have many small fracture points, such that recovery is possible relatively swiftly in the event of failure. The Russia-Ukraine war, and now the quickly evolving U.S. position, make clear the extent of the damage that can be done when fracture points are as large as they currently are, due to the presence of overexposure to such dominant positions. What is unfolding today is as much a story of global resiliency as it is about the eccentricities of America’s current regime. The jeopardy, however, is that at the speed with which countries are attempting to respond, the most important point may be lost.

Simply stated, that point is this: America is not the problem, concentrated power is the problem. Of course, in more pleasant times, under benign stewardship, concentrated power may seem like a solution, especially when it aligns with one’s own interests. As humans, we like brands, we like the simplicity of a single story that tells us what something is and assures us that it will stay that way. The illusion of safety. The bankable. The guaranteed. And the bigger the better. Marketing relies heavily on this tendency: our preference for “franchise,” for the proven – and our aversion to the new and untested. What is true in business is also true on the global scale. We see the small, the nascent, the powerless as risky, and the large, the stable, the well-funded as safe. There is such a thing as a national brand — and, in recent memory, few have been more effectively managed than that of the United States. Much of the world doubled and tripled down on this brand, and now that it is not living up to its promise, we are deeply disappointed.

As they say, “never waste a good crisis.” There is before us a unique opportunity to reassess risk at a global level and envision a global economy that boasts the resilience offered by decentralized power and control. For this to happen, we must let go of our attachment to the “franchise” and begin to take educated risks on a multitude of stakeholders (in this case, nation-states) that can offer the diversity and heterogeneity required for a healthier set of lower-risk relationships. This should involve taking a good, hard look at Africa.

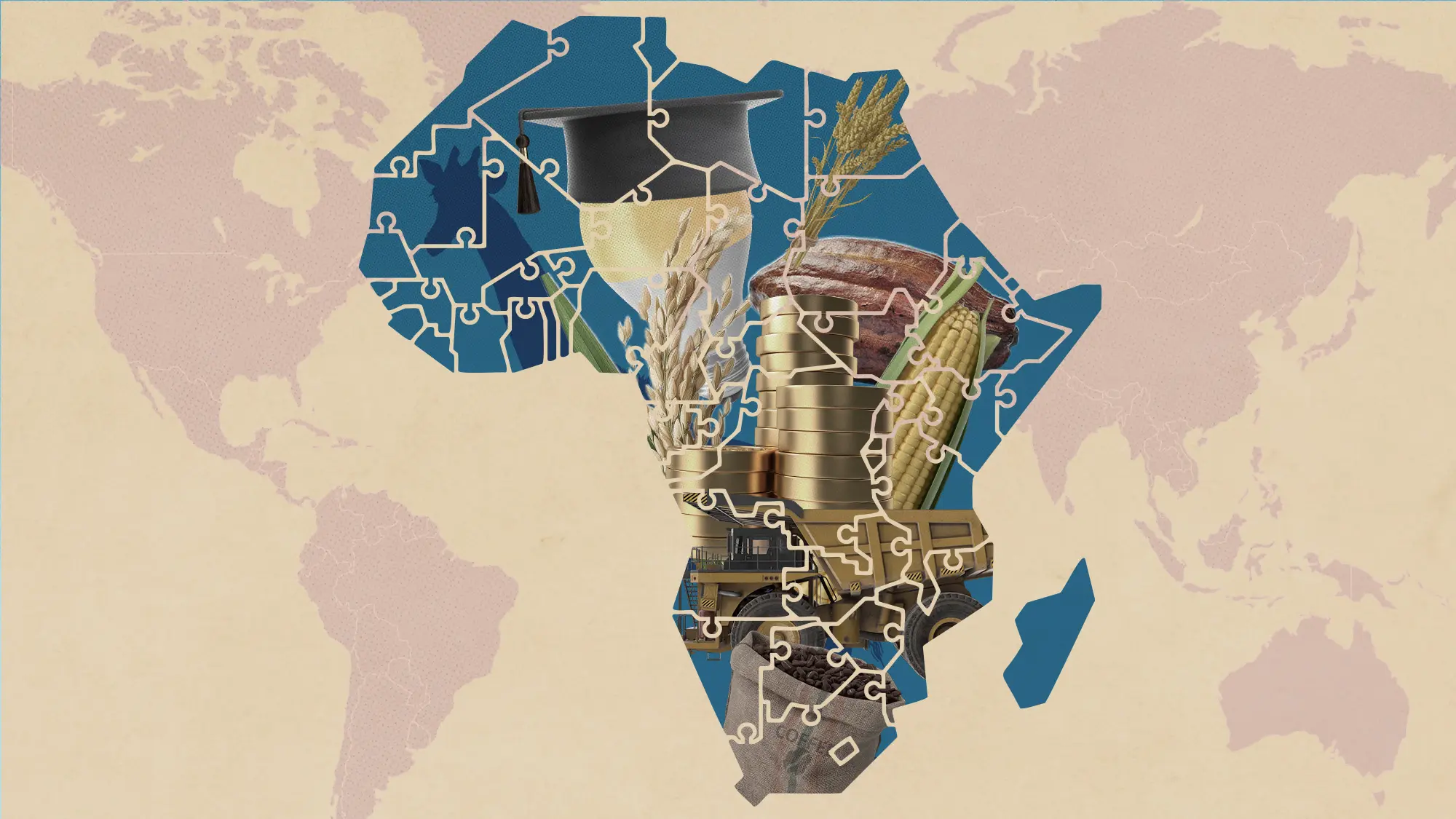

There is no other region in the world that offers the combination of resource richness, strong growth, untapped productive potential and crucially, national diversity like Africa. Asia is dominated by China, North America by the U.S. and while Europe does offer diversity, its aggregate GDP is roughly equal to that of China alone. Africa, by virtue of its history and topography, has always been a continent of great diversity. Its vast north-to-south span means that it encompasses many weather systems, permeated by pockets of harsh landscapes that have been difficult for kingdoms of the past to traverse when attempting to extend their reach. The fact that colonization occurred just as Africa’s existing kingdoms had fragmented meant that, instead of consolidating into a larger political identity – like India, for example – the continent became a patchwork of smaller sovereign nation-states. Add to this diversity a youthful and growing population, quickly maturing markets, and the benefit of a tech-enabled GDP push, and it is easy – at least theoretically – to understand the arguments for Africa as a future counterbalance to a global landscape still reliant on, and subservient to, the hegemony of a few.

There is much work to be done to unlock the continent’s potential, but the crucial switch to be made is attitudinal. Post-colonial Africa has largely been treated like a basket case, incompetent and incapable of contributing on the world stage. While there have certainly been enormous growing pains as African states come into their own, the broader context has been one of concerted neo-colonial pressure from former colonial powers that emphasize their interests first and foremost – often at the expense of African growth. The provision of conditional aid by Western nations, and the often heavy-handed structural adjustment programs meted out by the World Bank and IMF have been typical of the ways the West has dealt with the continent – such policies have been headwinds to progress.

However, there is an alternative to this zero-sum approach to the continent. Win-win, commercially oriented relationships with African nations have always been on the table – for example private sector focused investments that emphasize in-country production rather than extraction – they just haven’t been pursued with the necessary degree of seriousness. African countries and their leaders experience this as fact, and act accordingly – limiting their own visions for what can be expected out of relationships with the developed world.

Now imagine the emergence of a more strategic approach to Africa, one that recognizes the world is best off when African economies can reach their potential. This would mean leveraging the continent’s vast resources to create new markets, improve food security, address supply shortages, provide much-needed labor (remotely if need be), diversify trade flows – and, importantly, do all of this under a system of highly decentralized control: a polylithic economic superpower. That is, a continent with the economic resources and geopolitical weight of a China or a U.S., but with a fragmented structure – comprising many sovereign states – that ensures a broader range of interests is considered whenever influence is exerted.

The obvious response to this proposal is that Africa is simply still too small, as an economic force, to play this role – too small to take on the level of economic activity required to seriously reduce dependence on economic behemoths like China and the U.S. While that fact is certain, it is also subject to change. In the space of three decades, China’s GDP went from $360 billion in 1990 (6.25% of the U.S. GDP at that time) to $17 trillion today, roughly 60% of the U.S. GDP. So, these changes do happen, and in the 21st century, they can happen very quickly. Rather than just planning for this potential level of growth in Africa, there is an opportunity to actively participate in bringing it into being. Countries like Kenya, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Uganda, Senegal, and Nigeria are well poised to hasten their ascent up the ladder of prosperity, and if they succeed, others will follow.

It may not seem intuitive to assist in the development of future competitor economies, and doing so would represent an unprecedented shift in foreign policy for most nations. But the globalized world we now live in is simply too interconnected to regard national interest as separate from the interests and performance of other economies. China certainly understands this (whatever one thinks of its motivations), and is well ahead in making Africa an ally and key destination for investment flows into several key sectors.

The question is this: Do we believe the post-colonial, post-World War II playbook makes sense of the world as it currently is? Or does our thinking need to take a radical step forward, using the information we are gaining, rapidly, about the nature of global risk? Can we begin to see the many countries on the margins of global prosperity as critical parts of a potential new order, anchored in diversity and dispersed power – and with that, increased resilience?

This would include financial resilience; resilience in commodity markets reducing exposure to shocks; a broadened set of security agreements that bring the burden of global security under the purview of the majority. We would have newly minted, multi-stakeholder-led international agreements covering everything from trade to human rights law, reflecting the needs and values of a broader set of stakeholders – making it less likely that new centers of dominance (or weakness) will emerge. Simply put, we would have a global order fit for purpose, one built for the many, not the few.

Beyond the somewhat “cold” question of risk, there’s another question of a moral nature. While some may mourn the passing of the global order established over the last 70 years – the so-called rules-based society – for much of the world, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere, those rules have never worked in their favor. They see the deck as stacked, heavily, in favor of the Global North. Many see the crumbling of the established order as an opportunity to rewrite fairer, more just rules that don’t assign influence and wealth in well-established patterns of regional dominance. The fact is, the old system was creaking well before Trump’s arrival. It had already failed far too many. He simply pushed it over the edge.

In the ruins of the edifice lies a unique opportunity to look outward with fresh eyes, to stop running into the towers of old and begin building bridges, genuinely anchored in hope for a renewed global community. The unique promise of Africa is that it is a continent filled with diversity and replete with potential, waiting to be unleashed and to take its place on the world stage. What if we began to take risks worth taking – working in partnership with nations that have been chronically undervalued? It may be a harder path in the short to medium term, but that path will build the structure and resilience needed for a global order set on much firmer foundations.

© IE Insights.