Essential characteristics of the Internet as the new information infrastructure

The Internet can be thought of as an enormous supermarket managed by a handful of technology giants (namely, Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Twitter) which have become the new intermediaries in the digital public communication process by displacing traditional media companies. It is in this market where millions of us interact with infinite pieces of information and where we, as citizens, register an exponentially increasing number of information options that are personalized through various filters and algorithms designed by these tech giants. Our activity is converted into data that can be replicated, compressed, stored, manipulated, and then sold to their advertisers.

Of all the aspects mentioned above, the one that presents higher risks to our democratic life is the increasing surveillance of our online activity, which is converted into data that can be manipulated through algorithms to offer us personalized content and better catch our attention.

It is thus our attention that has become the technology giants’ main commodity – and the ways in which they capture it is being continuously refined and sophisticated. Another risk to our democratic life is the concentration of power in the hands of these five technology corporations. This oligopoly is far from the utopian libertarian idea of what the original Internet creators of the mid-90s had in mind when they envisioned a new system that could bring back the power to us, citizens, away from corrupted institutions. As Mathew Hindman noted regarding the Facebook-Google duopoly, in his book The Internet Trap, “What we have built on the Internet is not an ecosystem, but a pair of commercial monocultures.”

The new post-truth ethos and its impact on liberal democracy

There was once a time in which the traditional news media played an integral role in determining what topic captured the public’s attention. Journalism scholar Maxwell McCombs details this phenomenon in his seminal book, Setting the Agenda, concluding that the Internet has brought “the end of [conventional media] influence in the agenda setting as we have known it for the past decades.” Or, in the words of Andrew Shapiro in The Control Revolution, “net users will shake the base of the Fourth State.” Nonetheless, as the Internet’s dynamics and infrastructure concentrates in a handful of technology companies, whose main goal is to sell our attention to advertisers, a new edition in the same family of risks is emerging for us as digital citizens.

Millions of citizens in this global digital democracy are building their own reality.

To begin with, technology companies are setting the rules of the game not only for themselves but for the conventional media companies, who must also compete for our attention. The end result is that many media companies follow the new rules of the game, mainly: attract more followers, generate more comments and shares. Success is dependent on the essential attention drivers, the ideological component and, even more so, the identity factor. As a side effect, the professional journalism of the last quarter of the 20th century is losing ground to what New York Times columnist and Vox co-founder Ezra Klein considers a new radical “identity journalism.”

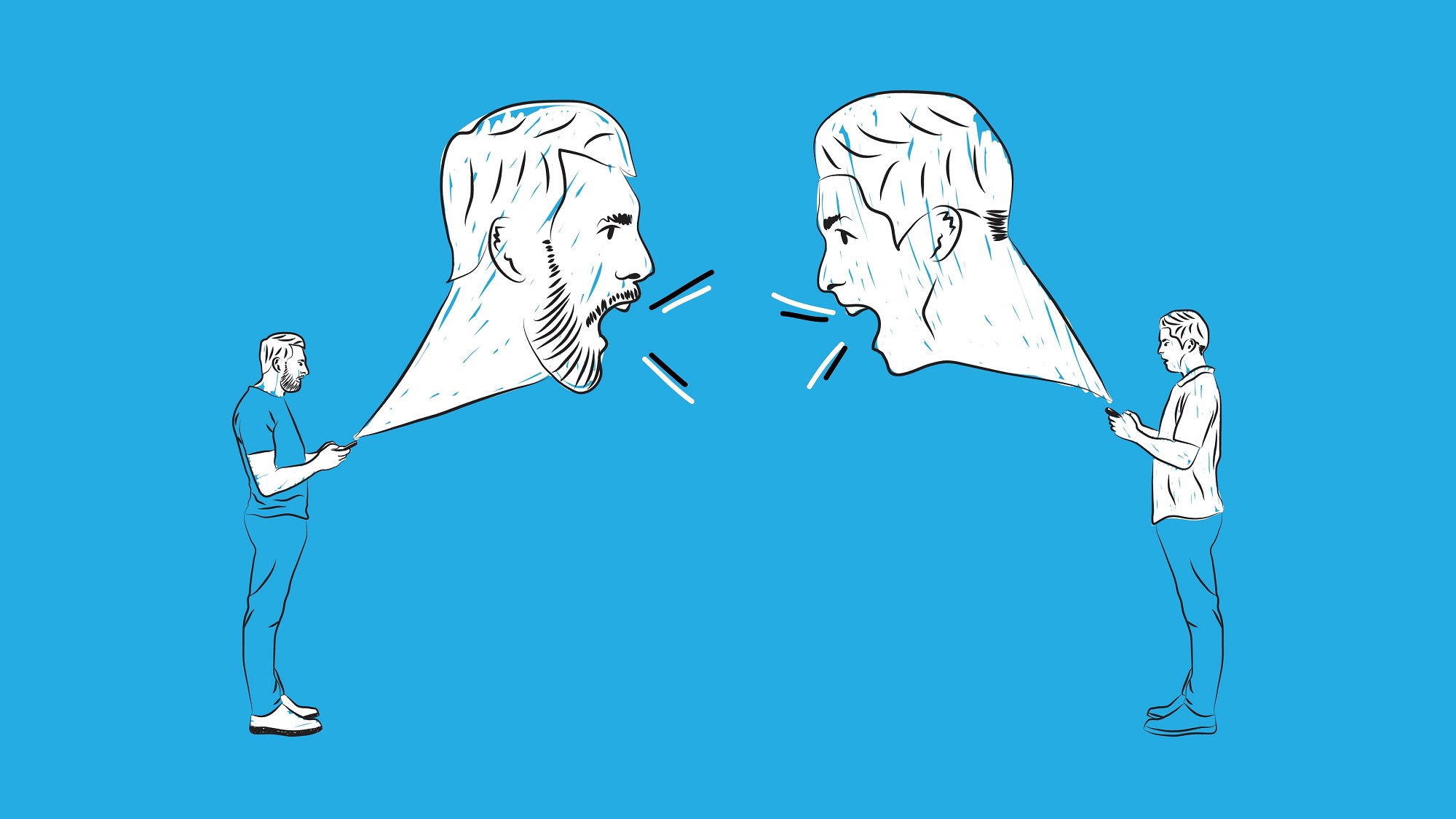

The appeal to our group identity in the digital context continually feeds thousands of online communities (aka “echo chambers”). The possibility that each one of us can filter and organize information according to our preferences in a society motivated by hyper individualism and a “psychology of control” leads to the Daily Me phenomenon, as coined by Nicholas Negroponte. Millions of citizens in this global digital democracy are building their own reality, mostly based on radical opinions and beliefs, and, unfortunately, on disinformation and fake news.

We are caught in an “identitarian” online community that employs a destructive emotional process to alter our capacity to think clearly and with full attention. In this way we have become polarized and wary of any information that runs counter to our (biased) belief system. As Klein wrote in his recent book, Why We’re Polarized, it is much more difficult to change a belief based on emotional identity than to change a rational opinion. And today, thanks in part to the identity-centric media landscape and the constant manipulation of the technology giants, there is really no wonder why much of our belief system is fueled more by emotion than fact. As a result, our public conversations, particularly on the blogosphere, are fragmented, emotionally destructive, and politically polarized. Without a common ground of truthful facts, we are prey to the agendas of advertisers and populist leaders.

Welcome to the post-truth ethos.

Rebuilding an enlightened “ethosphere”

In order to preserve the freedom and human dignity that is guaranteed only by a well-established democracy based on the liberal enlightenment ethos, it is our responsibility as citizens in the post-truth era to be vigilant of the risks embedded in the digital environment.

There is a long-standing debate regarding what role citizens, press, and political decision-makers should play in the democratic process. At the beginning of the 20th century, Walter Lippmann and John Dewey concluded that neither the citizens nor the press had the capabilities to secure a good government in a democratic context. Both Lippmann and Dewey agreed on the solution: the need to create an independent agency integrated by a group of high-level experts to carry out social and political research that could be transferred to the dynamic process of public affairs and political decision-making. However, they offered different (and rather opposing) solutions.

There need to be new agents that can curate rational and enlightened debates among high-level experts and civil society.

In his famous 1922 book Public Opinion, Lippmann chose the elitist and aristocratic solution. He was convinced that the public was incapable of making informed, enlightened decisions. As a result, he defended that the intelligence of the experts should only be shared with the government, excluding the public from the decision-making process, aside from voting. To the contrary, Dewey, defended a democratic approach. His solution was to communicate the experts’ intelligence to the general public in a pedagogical and even artistic way, appealing to constructive and positive emotions.

Contemporary philosopher Martha Nussbaum defends a similar approach as Dewey. In today’s digital environment, Dewey and Nussbaum’s vision actually gains new ground. Well-educated citizens, when under the right information infrastructure, are capable of reaching informed decisions and political consensus. As the University of Canberra’s John Dryzek and his fellow researchers proposed, “social science on ‘deliberative democracy’ offers reasons for optimism about citizens’ capacity to avoid polarization and manipulation and to make sound decisions.” There need to be new agents that can curate rational and enlightened debates among high-level experts and civil society that can complement parliamentary and governmental activities. This notion gets closer to the liberal conception of critical public opinion that Jürgen Habermas defended in his first major work.

In addition, the role of the press becomes more and more essential to effectively communicating truthful and expert-based information to the public at large. But in order to make their brands attractive and credible, media companies must invest in transparency and governance policies that allow public access and engagement. The good news is that, as a result, many experts are predicting an increase in media brands with a strong ethical reputation.

More importantly, we are finally beginning to correlate our right to attention with our right to information. Alongside the art of enlightened debate, the right to attention and information should be recognized as essential components of a digital citizenship curriculum. According to neuroscientists, philosophers, and psychologists, attention is the foundation on which we build our cognitive and emotional processes, on which we condition our critical thinking and, most importantly, our capacity for well-being and happiness. The father of American psychology, William James, insisted in his 1890 book The Principles of Psychology that “geniuses are commonly believed to excel other men in their power of sustained attention…the faculty of voluntarily bringing back a wandering attention, over and over again, is the very root of judgment, character, and will.” In fact, signs of the impact of the Internet on our attention are now starting to emerge. For example, according to French neuroscientist, Michel Desmurget, digital natives are the first kids with an IQ lower than their parents.

In sum, the Internet poses a number of risks to our democratic project and our public life – none of which can be ignored. But these risks can be countered by a public sphere inspired by the liberal enlightenment tradition. This “ethosphere” can be built via spaces of deliberation and conversation, in addition to the activity of ethical media companies that provide – in a pedagogical and artistic way – truthful and expert-based information, and with the nurturing of enlightened citizens, who deserve to enjoy effective rights of attention and information. Sustaining our democratic project is a necessary endeavor of present and future generations.

© IE Insights.