Across nearly every sector of the world’s economies, on average, the total impact of family businesses to global GDP is more than 70%. China is no exception: since the economic reforms of the late 1970s, huge numbers of private family enterprises have been set up and now play a major role in the economy. The contribution of the private sector to GDP in China has grown to at least 60% in recent years, of which 85% are from family-owned private enterprises, making a major contribution toward technological innovation, as well as creating jobs.

However, given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, as well as other aspects of uncertainties in today’s business environment, Chinese family businesses, like the rest of the world, are facing severe challenges. What makes Chinese family businesses unique from their peers in western countries is the Chinese culture and its impact on the strategies and operations of Chinese family businesses. Based on cultural comparisons and 20 recent interviews of Chinese family business owners, I explore the question of how the COVID-19 pandemic may affect Chinese family businesses and their strategies in the post-pandemic economic recovery, and whether it is possible to replicate these strategies in the context of other countries.

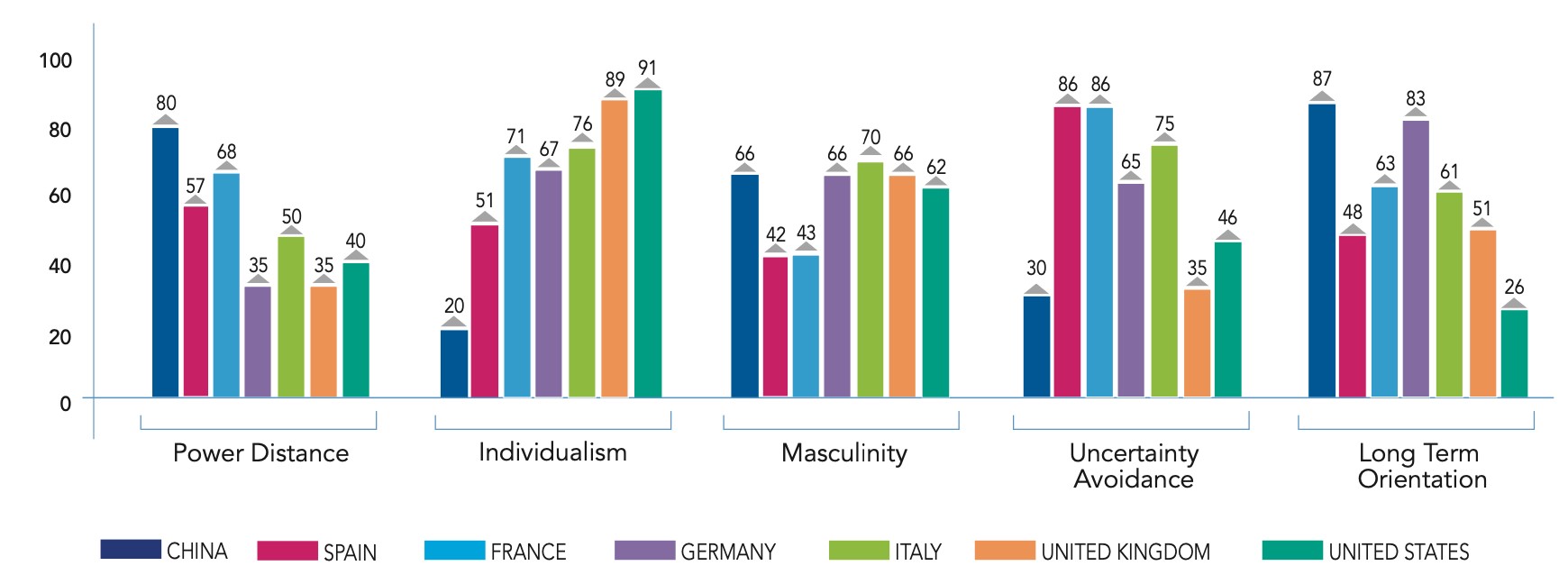

Countries and regions have reacted to the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic in different ways, which can be explained, at least partially, by the cultural norms that shape people’s behaviors. Research in the cross-culture management field identifies these dimensions that distinguish cultures from one another: power distance; individualism versus collectivism; masculinity versus femininity; uncertainty avoidance; and long-term orientation versus short-term orientation.

Figure – Cultural Comparison among Seven Countries

Source: Hofstede Insights

National cultural differences, as well as the challenges, resources, and strategies of countries differ, and thus the shape and manner of business recovery in the post-pandemic period will likewise vary by country. These cultural differences can also help us understand Chinese family businesses and how other countries can develop future collaborations.

Power distance describes people’s level of acceptance of unequally distributed power. This dimension has a big impact on the relationship between government and society; thus, it has been considered one of the biggest cultural differences between China and most Western countries. In my interviews with Chinese family businesses, owners expressed a high degree of confidence in the effectiveness of the Chinese government’s recovery policies, which is a good example of the impact of high power distance. French culture also shows a relatively high score of 68, followed by 57 for Spain. Thus, French and Spanish companies are able to identify with and acknowledge the importance of respect in Chinese society and business, which in turn eases collaboration between companies of these countries.

Of course, collaboration is not impossible amongst companies of differing power distances but executives and business owners in countries with a low power distance, such as Germany, must work a bit harder in this respect. They can start with small gestures that recognize the power dynamics and signal respect, which is particularly recommended when the Chinese business partner is significantly older in age or occupies a more senior position. For example, in the initial stage of developing a business partnership with Chinese companies, gift-giving is a good way to break the ice, regardless of the gift’s value.

Individualism versus collectivism indicates the independence/interdependence among people in a society. Chinese culture shows a low level of independence and a high level of interdependence. In Chinese society, people tend to make collective decisions based on shared resources. Moreover, members of a collective society prioritize in-groups, such as family members.

As reflected in my interviews, most Chinese family business owners have been relying primarily on family and friends for financial help during the pandemic and recovery. Spanish culture enjoys a balance between individualism and collectivism, scoring 51 in this category. Although Spain’s score is higher than China’s 20 it is still significantly closer than the other five countries which range from 67 to 91. This balance in Spanish culture provides an advantageous position for business owners from Spain to cope with the collective tendency of Chinese society. In China, people highlight the value of in-group friendships, dependency among family members and collective decision-making, even in a business and professional context. It takes time to break into an inner circle, but the effort usually pays off.

Masculinity indicates the extent to which a society is driven by competition, efficiency, achievement and success, meaning that many people are prepared to sacrifice family and leisure time when necessary. China scored a 66 in this category and the rapid growth of the country’s economy provides some evidence of this shared quality among Chinese people, especially the owners of family businesses. For those executives in countries with a similarly high score of cultural masculinity (66 for Germany, 70 for Italy, 66 for UK, and 62 for the United States), the seeming obsession with efficiency and achievement in successful Chinese enterprises is not considered unusual – but executives and business owners in countries like Spain (42) and France (43) have difficulty understanding their Chinese business partners’ “rhythm” at work.

Uncertainty avoidance describes how severely people feel threatened by ambiguity or uncertainty and, thus, tend to avoid them. A low score, such as 30 in the case of China, is viewed favorably at a time of crisis and uncertainty because it indicates that people can coexist with uncertainty and tend to be more flexible, adaptable, and entrepreneurial. This is the most drastic cultural difference of the group. China, the United States, and the United Kingdom all score low in uncertainty avoidance, while Spain, France, Germany, and Italy have very high scores. When doing business in China, people from high-scoring countries in terms of uncertainty avoidance must endeavor to be more flexible than they are accustomed to and to prepare themselves for surprises: most rules, and sometimes the important ones, are left unsaid. As is true in all parts of life, in order to avoid misunderstandings or incorrect assumptions, it is best to simply ask when there is doubt. By doing so, you are showing interest and seriousness, which is an act of respect, something a Chinese business partner understands well and will thus be more than happy to explain whatever situation is at hand.

Long-term orientation shows a society’s link with its past while dealing with the present and the future. A high score in regards to long-term orientation is associated with significant levels of saving, which are particularly important in times of uncertainty. In general, Chinese people are long-term oriented; they plan ahead, and they develop and maintain lasting relationships with their business partners. This may be why the business owners I interviewed expected a speedy post-pandemic recovery. In fact, my interviews with Chinese family business owners showed that, in most instances, they put their business partners as their second source of financial help, after family. Building trust and creating collaborations takes time, especially in long-term oriented societies like China and Germany. However, with patience, a bond can be developed between long-term oriented countries, one that is usually strong, sustainable, and beneficial. A society that is oriented towards the long-term is quite advantageous, and thus partnerships with Chinese and German companies are particularly valuable in times of uncertainty and crisis.

Chinese family businesses are likely to recover relatively quickly from the COVID-19 pandemic because of the way cultural values shape their strategies in terms of setting long-term visions and strategic goals such as building synergy with business partners, reserving more cash flow for risk control, and developing a trust-based relationship with the government. It is essential for Western companies to understand not only how culture plays an influential role in the way Chinese family businesses are run but how it compares to their own – this is the awareness that will help Western companies develop and sustain partnerships in China. And these collaborations will prove to be increasingly valuable as China’s economy gains strength and, with the help of family-run businesses, play a pivotal role in the global economy.

© IE Insights.