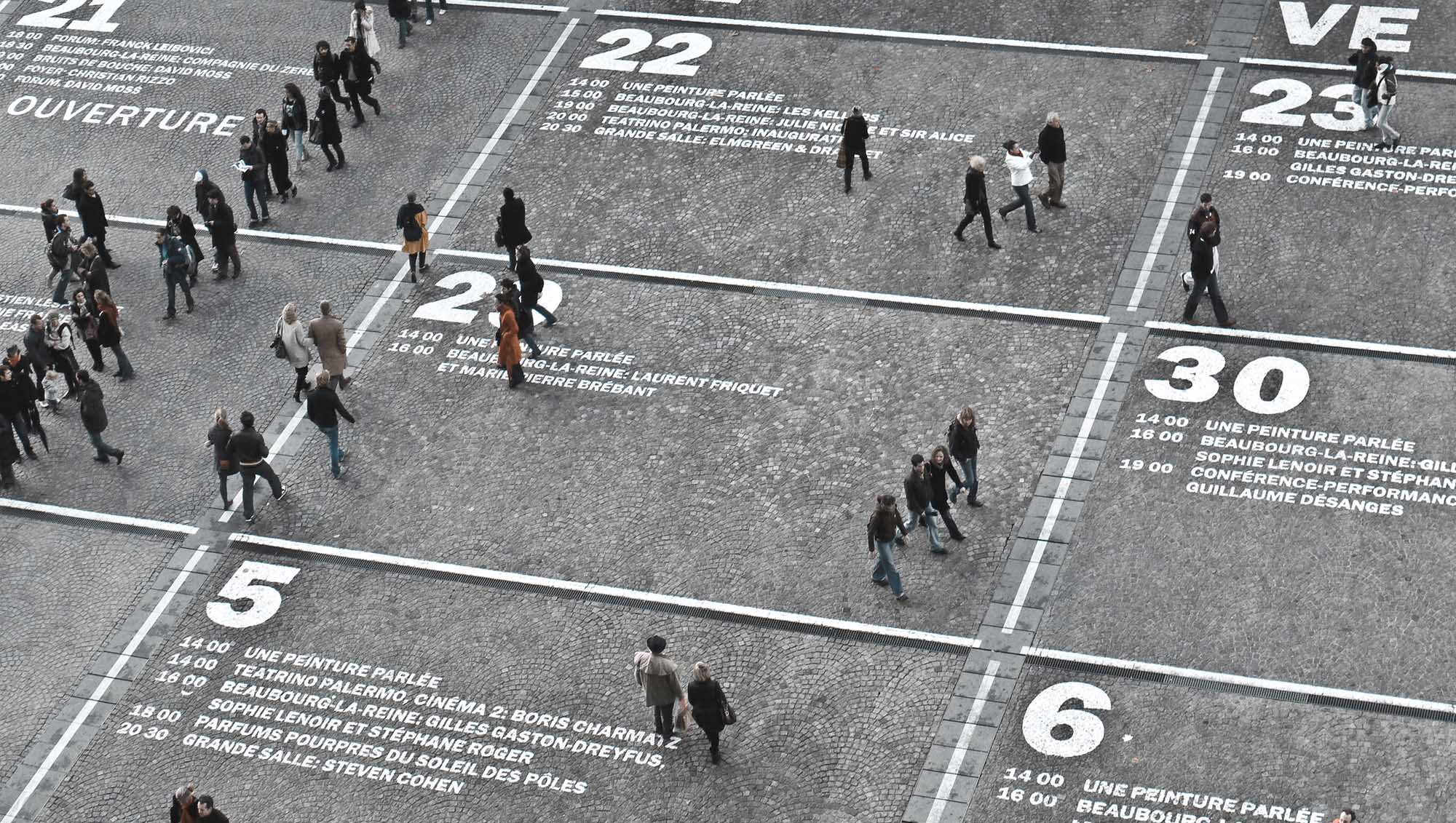

An urbanite is defined as someone who is “comfortable with the customs of city life.” In the most literal sense of the term, city planners are taking a profoundly urbanite turn by designing activities and spaces that encourage social interaction.

Recreational facilities, stores, public buildings, infrastructure, workspaces, and even transport are being reimagined as “third places”—settings that generate social experiences. Paradoxical though it may seem, any corner of a city can achieve this goal.

The term third place was coined by the sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his 1989 book The Great Good Place. In Oldenburg’s telling, the first place is your home and the second place is your place of work. The third place, no less vital to individual well-being, is the realm where a community’s social life plays out.

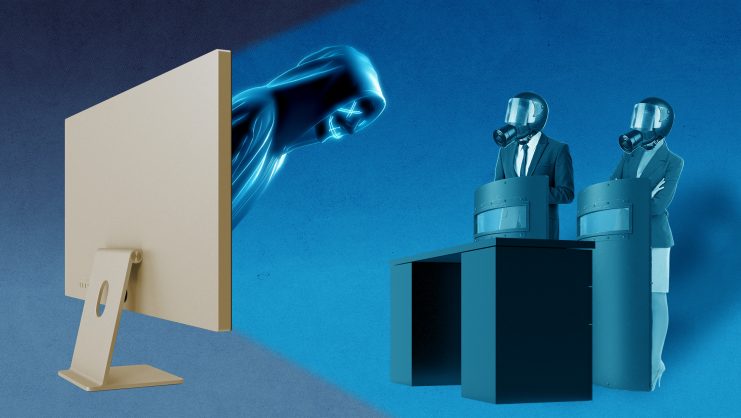

At places of employment, the barriers separating work and leisure—not to mention the physical and digital worlds—have become blurred.

Transformations in search of social essence

Social interactions, human contact, and interpersonal relations define the health of contemporary urbanites. Private and public initiatives have developed environments that seek to maximize these factors. London’s Boxpark, a pop-up mall built from shipping containers, features shops, restaurants, art galleries, and office space for non-profit groups. Major retailers such as Nike, Calvin Klein, and Lacoste have taken part in the project, which was first launched in 2011 and has since spread to other cities across the globe.

Another example is Madrid’s Matadero. This former slaughterhouse is now a city-owned facility for activities quite unlike its original purpose. In essence, the Matadero is a cultural laboratory where ideas from a wide range of disciplines are shared. Users help to create and spread culture, taking part in a democratized process previously reserved for elite creators and producers. The Matadero grounds also feature recreational spaces, cafés, bars, and communal kitchens.

At places of employment, the barriers separating work and leisure—not to mention the physical and digital worlds—have become blurred. Hyperconnected offices have remade the very notion of the workplace. What was once a place where attendance was required in order to perform a particular activity is now a hub, a meeting point, a space designed for comfort. Nowhere is this clearer than at coworking spaces, where interpersonal interaction is a major draw.

Numerous coworking startups have emerged in recent years, including Regus, WeWork, Utopicus (subsidiary of Colonial), Spaces, Aticco (in Barcelona), Negocenter, and Monday. Despite the recent upheaval at WeWork, it is clear that the demand for shared workspaces is on the rise.

Coworking spaces are attractive to millennials, a generation that is generally reluctant to commit to a particular organization. The promise of networking in the workplace has proved persuasive to this demographic.

Thanks to the advances of numerous tech firms, hyperconnectivity now dominates our public space and will soon be available on most modes of transport, making work truly ubiquitous.

In today’s hyperconnected world, loneliness is on the rise in every age group.

Instagram: a third place?

The virtues of the third place extend to certain virtual environments. In recent years, Instagram has emerged as the social network with the greatest potential to serve as a third place.

But what will happen as the physical and digital worlds converge? If we can satisfy our need for human contact from the comfort of our own homes, do we even need physical spaces? Around 2.5 billion people play online video games, so gamers have countless opportunities for interaction. Similarly, mobility services like Lyft, Uber, and Cabify could become third places by promoting interaction and comfort. Future generations may not even need to leave their homes in order to interact with other people. The big challenge for cities will be to combat the silent global epidemic of loneliness.

Although loneliness is not recognized as a clinical disorder, the World Economic Forum, citing a study by Utah’s Brigham Young University, has identified this condition as one of the greatest threats to people’s survival. Research has shown that social isolation can increase the risk of early death by up to 50%. Paradoxically, in today’s hyperconnected world, loneliness is on the rise in every age group. Now more than ever, third places are a crucial component of the urban fabric.

© IE Insights.