The companies that are going to last will be the ones that prove able to adapt to the ever faster changes in customer demand. The new generations look to share rather than own goods and services. In this environment, the digital transformation and crisis have propelled the sharing economy to meet real and potential needs, such as car or holiday apartment rentals. One can point to hundreds of great start-ups and well-established companies based on the sharing economy, firms that are thriving today in all sectors thanks to millennials.

Companies have to adapt to these changes, taking advantage of niches to develop subsidiaries to capitalize on new business opportunities by industry or rethinking their strategies to be more efficient in various functional areas. Customers do not need to own the good, just enjoy it. In this context, we can measure the degree to which a company has embraced the sharing economy by rating its operations and functions and then weighting them by industry. These variables will allow us to analyze weaknesses and implement ideas for improvement.

The sharing economy is driven by several factors, including the Internet, new technologies, the use of the latest mobile devices to stay connected all the time, and the crisis. Millennials are another important piece of this puzzle. They are the generation born between 1980 and 2000, a generation that is always on and always connected, very highly educated, and lacking in opportunities. Companies need to understand this reality if they are to suitably address these new consumers, people who are far more focused on what they actually need, which is not ownership of a good, but the ability to enjoy it, and who are willing to forego a certain amount of quality – the brand’s more incidental values, say – for a good price.

We are trading ‘I’ for ‘we’, ownership for access, global for local, etc., constantly looking for opportunities to share and to make community much more important than advertising.

Empowering the Individual

People are the cornerstone of the sharing economy. The aim is to empower individuals so they can maximize their assets and skills and offer their services. We are trading I for we, ownership for access, global for local, etc. We are decentralizing, constantly looking for opportunities to share, placing people at the core, and striving to make community much more important than advertising. We see this in the rise of Netflix, the TV channel with the greatest potential, despite being cable-free; Alibaba, the largest global retailer, which has no stock; Instagram, home to the largest collection of photos, but not a single camera; and Uber, which has the world’s most extensive taxi fleet, but does not own a single vehicle.

At the same time, reputation is becoming increasingly vital in these communities. We are shifting from B2B (business to business) to P2P (peer to peer), from hyper-consumption to collaborative consumption.

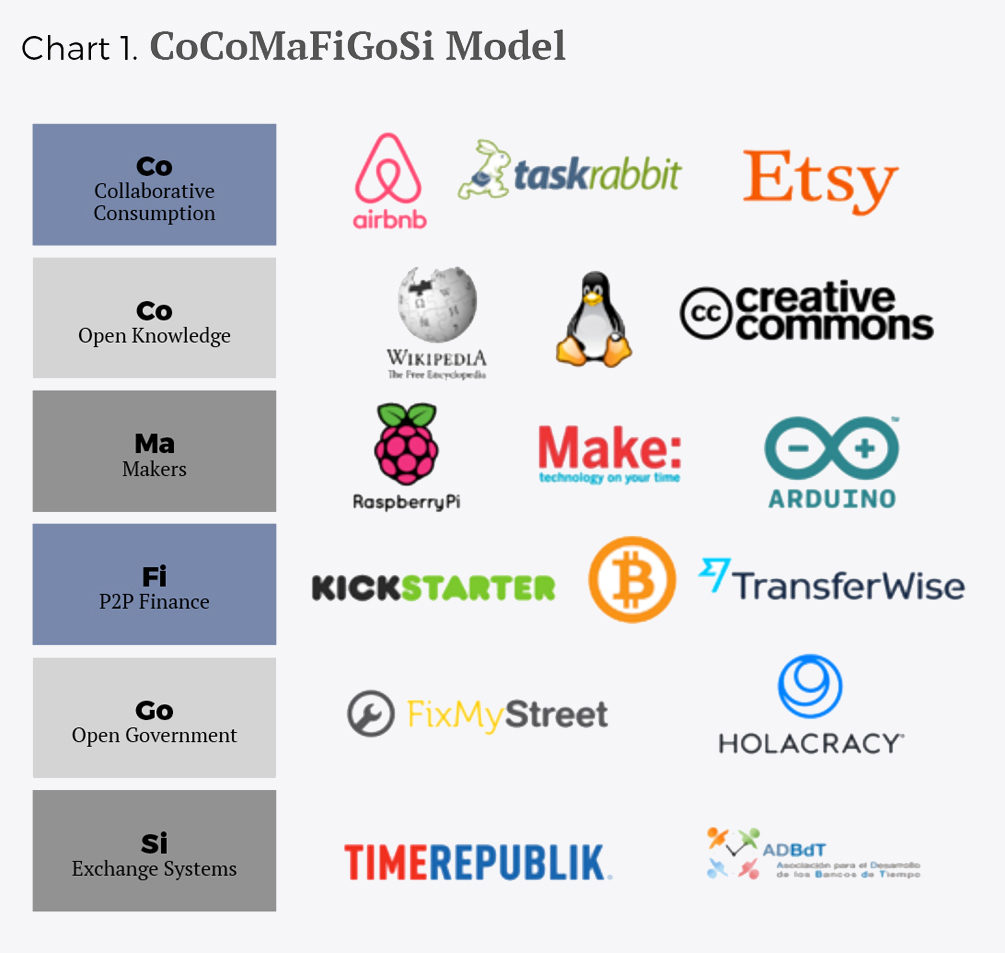

Sharing economy companies fall into six main categories, a model we call CoCoMaFiGoSi (from the Spanish; see Chart 1), which stands for: collaborative consumption, including major platforms like Blablacar or Airbnb; open knowledge, such as Wikipedia, Linux, or Creative Commons; makers or groups of people who come together to create, collaborate, and share; P2P finance, such as fintechs or bitcoin; open government, such as the FixMyStreet platform; and exchange systems, which allow people to share skills and goods.

Prosumers

In 2006, the world’s five most powerful companies included two oil companies, an industrial group, a bank, and a technology firm. Today, the companies that top the ranking are all in tech. In 1951, the world’s 500 largest companies had taken an average of 75 years to get where they were; this time period had shrunk to 25 years by 2003, and to 10 by 2015.

In light of this reality, the question is not how long it will take for one of the world’s largest companies to be a sharing economy company, but which sector it will come from, because no industry is immune to these changes. Two examples are Volkswagen and Toyota, which have undertaken sharing economy initiatives. While the German company invested more than €250 million to acquire a stake in the ride-hailing company Gett, the Japanese multinational did not stand idly by but rather chose to help Uber grow by providing strong technological support for the development of an autonomous car.

The question is not how long it will take for one of the world’s largest companies to be a sharing economy company, but which industry it will be in.

Once upon a time, we could be producers or consumers; now, on any of these platforms, we are prosumers, i.e., people who can both produce and consume. One example is Wallapop, which allows you to sell and buy at the same time. However, using these platforms requires trust. Traditional companies are beginning to wake up to this fact. Some large insurers are already teaming up with Spanish start-ups specialized in reputation management to design a system whereby, for the same amount of money, someone with seven positive ratings will be able to purchase an X plan, while someone with fifteen positive ratings will be able to purchase an XX plan. In other words, the aim is to monetize our online reputations. The trend is toward the use of different reputation systems on different platforms; if we use Uber, not only do we rate the driver, but the driver rates us, and that rating is recorded.

On the Internet, reputation has become the new currency. Trust is crucial on these platforms; formerly small circles of trust have grown large with the Internet. Consequently, what was once merely a stranger is now a stranger with a rating, someone we would catch a ride with, eat with, or let sleep in the room down the hall. In the sharing economy, there are three pillars of trust: the platform itself, an area in which Airbnb paved the way and continues to excel; the feedback provided by the community; and, the most complicated of all, the legal environment. Often, believing we are doing something illicit will either give us pause or pique our interest.

© IE Insights.