Employee wellbeing during COVID-19

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been rapid changes in working conditions on a global scale, challenging the wellbeing of millions of employees around the world. This report investigates the short and long-term effects of COVID-19 on employee wellbeing and urgent changes needed regarding the topics and delivery formats of corporate programs.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been rapid changes in working conditions on a global scale, challenging the wellbeing of millions of employees around the world. This report investigates the short and long-term effects of COVID-19 on employee wellbeing and urgent changes needed regarding the topics and delivery formats of corporate programs.

In this report, I cover what topics are most urgent to focus on right now and why (mental health, stress and sleep). I discuss the research showing a bidirectional relationship between stress and sleep, and how this is especially important during a crisis. I outline the particular sleep challenges and opportunities employees face during the COVID-19 outbreak. Finally, I discuss what format requirements are needed now, with a focus on digital, community-based and programmatic approaches.

About the author: Dr. Els van der Helm, adjunct professor at IE Business School in Madrid, cofounder of Shleep and named one of the top 5 sleep experts in the world, shares her insights on critical topics and delivery formats that corporates need to address to ensure the wellbeing of their employees.

COVID-19 is having an unprecedented impact on everyone’s working and personal life. The dizzying pace at which this is happening leaves many CEOs, business leaders and HR departments all over the world scrambling to adjust quickly to the “new normal”, whether it is a large part of their workforce suddenly working from home, at different times, doing overtime, different work or not working at all.

Given that it will be a matter of months, not weeks, means it is about so much more than the immediate logistical adjustments, such as changing schedules and remote working tools. It leaves business leaders asking, “How can I ensure the wellbeing of our people?”, “How to keep a sense of social belonging and community within my organization and teams?” and, of course, business questions such as, “How do I ensure a continuation of work and deliver on our company goals?”

Leaders that address the “new normal” by putting the wellbeing of their employees central in these difficult times, as opposed to an afterthought, will be those who get through the crisis in a better way; come out stronger with a workforce that felt protected, cared for, appreciated and, importantly, healthy and resilient, during an incredibly stressful time in their life. In addition, these leaders will end up with a workforce more committed and engaged with their work, more connected to coworkers and more likely to stay in the long term. Moreover, another important point will get is a workforce, who feels better, is better set-up to continue their work during a crisis.

However, how exactly do you support your employees’ wellbeing during a crisis like this? Despite there not being a “playbook” for this unprecedented situation, there are pre- existing trends that will become stronger given the current demands and some COVID- 19-specific opportunities and challenges that need to be addressed in a completely new way.

Here I would like to focus on two dimensions of wellbeing offerings that companies should boost in order to adjust well to COVID-19: one related to the topics addressed and one related to the format of delivery. In terms of the topics to address, I will touch on mental health, stress and in greater depth: sleep and stress. Regarding format of delivery, I will discuss the need for digital, community and programmatic approaches. Although these aspects were already present and important pre-COVID-19, they are now even more urgent.

PUT MENTAL HEALTH FRONT AND CENTER

First off: This does not imply that physical health is not important or our very first priority. Thankfully, most companies have already taken the necessary precautions and measures focused on infection prevention, e.g., handwashing, social distancing, travel bans and coughing in elbows.

In times of crisis, mental health is under great pressure, but the topic and its costs to the economy had already begun gaining more attention. Firstly, the high frequency of mental health disorders has raised concerns: 18% of employed Americans ages 15 to 54 said, they experienced symptoms of a mental health disorder in the previous month. Secondly, the costs are staggering: The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that depression and anxiety alone cost the global economy US$1 trillion per year in lost productivity.

Employers have started to become aware that workplaces that promote mental health and support people with mental disorders are more likely to reduce absenteeism, increase productivity and benefit from associated economic gains. In fact, the WHO calculated that for every US$ 1 put into treatment for common mental disorders, there is a return of US$ 4 in improved health and productivity.

Despite mental health already being “on the agenda”, it deserves extra attention now. What is so worrisome about the COVID-19 crisis is that it affects everyone’s mental health: those with a pre-existing mental health condition are extra vulnerable because they have “less reserve” to deal with the additional stress. In addition, for those with no pre-existing mental health issues, the rapid and repeated large-scale changes caused by COVID-19 increase the risk of them developing mental health issues. After all, everyone is dealing not just with changes and associated stress in their professional lives, but likely in their personal lives as well. These changes range from suddenly being at home with other family members or even taking care of sick family members while being expected to get work done. In addition, many will worry about high-risk loved ones including parents and grandparents.

The fact that a global pandemic will increase most people’s stress levels is not surprising. The WHO has already warned that the sudden and near-constant stream of news reports about this outbreak can cause anyone to worry. Previous studies on natural disasters also underscore how such stress leads to a subsequent increase in mental health disorders. One well studied cohort in New Zealand showed that sub cohorts with high levels of exposure to the major Canterbury earthquake had rates of mental disorders that were 1.4 times higher two years later than non-exposed sub cohorts.

Where normally going to the office and work can provide some distraction and thereby stress relief, many employees will feel the stress cannot easily be escaped anymore, especially when confined in a “lockdown” where they cannot leave their home.

WHAT SHOULD COMPANIES FOCUS ON THEN, TO ADDRESS MENTAL HEALTH AND STRESS?

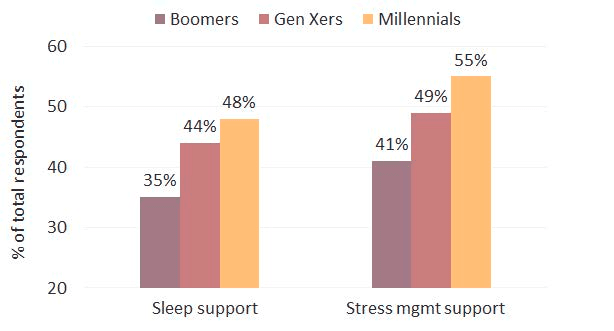

It is important that employees are offered wellbeing solutions that directly aim to decrease stress levels. There are several options available in this space, but here I would like to highlight an important component that we know critically and immediately affects mental health and stress: sleep. We know from several pre-COVID-19 reports that employees were already increasingly asking their employers for offerings on both stress and sleep (Figure 1), but given the urgent need to address mental health, it is helpful to review how these topics can help your organization now.

Figure 1: Percentage of employees wanting sleep and stress support from their employer (Source: 2017 Consumer Health Mindset TM Survey: Aon Hewitt, the National Business Group on Health, and Kantar Futures) Mental health and sleep

Sleep and mental health form a bidirectional relationship. On one hand, sleep is often disrupted when mental health is impacted, and on the other hand, sleep can function as a potential therapeutic aid in improving mental health.

It is beyond the scope of this report to discuss the breadth of mental health problems where sleep tends to be disrupted, but three major issues of relevance right now are depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). To better understand why sleep is often disrupted in these disorders and how better sleep can prevent and improve symptomatology, I will focus here on the impact stress can have on sleep (and vice versa).

- Impact of stress on sleep

There are plenty of anecdotal reports of people having issues with sleep when experiencing stress and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) specifically warns that stress during an infectious outbreak can lead to changes in sleeping patterns and difficulty sleeping altogether. Data on natural disaster survivors underscores this. One study, for instance, on survivors of the 2010 Haiti earthquake found that 94% reported subsequent insomnia after the disaster. Another study on earthquake survivors in China’s Wenchuan in 2008 found that 83% reported sleep problems even 17-27 months after the disaster.

Some studies have focused on trying to find exactly how the different stages of sleep (sleep “architecture”) are affected by stress. When reviewing these studies, it is important to keep in mind that stress, of course, is a broad term and can mean different things; ranging from a major stressful life event such as losing a loved one or going through a divorce to a mildly stressful computer task.

Studies looking at the impact of mild stressors on sleep in research labs found a large variety of sleep changes, ranging from an increased time to fall asleep (sleep latency), more awakenings, decreased rapid-eye-moment (REM) sleep and decreased deep sleep (slow-wave sleep), specifically in the first sleep cycle, so early in the night.

Other studies looked at real-life stress, e.g., small daily life stressors, and found that sleep was affected in a variety of ways but one consistent finding has been a reduction in deep sleep.

When studying larger stressful (life) events, sleep was further impacted: REM sleep started earlier and REM sleep increased in terms of percentage of total sleep time, whereas deep sleep here too was reduced. It is of interest to note that these changes in sleep architecture resemble sleep changes we also observe in depression. One particular study found changes in REM sleep persisted for almost 2 years after bereavement, which could imply a major life stressor has long-term effects on our sleep. However, such long- term findings have yet to be replicated.

Regardless of the long-term impact, the short-term findings explain why in stressful times our sleep feels less restorative and we might feel more exhausted. It could mean that though getting sufficient sleep during times of high stress is clearly difficult, we might, in fact, need more sleep to compensate for the lower quality, but such a hypothesis has yet to be tested.

It is of interest to note here, with the expected rise in loneliness among people working from home, that it is not just stress but loneliness that can lead to significant sleep problems. Self-reported loneliness has been linked to worse sleep quality 16, 7, 17, 18, while active socializing is associated with better sleep quality 19.

- Vice versa: Impact of sleep loss on stress

Stress not only impacts sleep but sleep loss impacts our subsequent stress levels, leading to, for instance, higher levels of irritability and emotional instability (Horne, 1985). When restricting sleep to just 5 hours per night in healthy individuals, they report increasing emotional disturbance and difficulties across just 7 days (Dinges, et al., 1997).

Another study looked at the effects of sleep disruption on emotional reactivity to daytime work events in medical residents (Zohar, Tzischinsky, Epstein, & Lavie, 2005). It revealed that sleep loss increased the negative emotional consequences of negative experiences while blunting the positive benefit associated with rewarding or goal- enhancing activities. Basically, negative events have a stronger impact and positive events do not lead to the usual boost in mood when we are tired. A recent study also found that sleep loss leads to increased feelings of loneliness, which during these times of remote working, highlights how sleep loss can easily exacerbate emotional challenges anyone can face during the COVID-19 crisis.

Brain imaging studies have found neural correlates of such behavioral differences after poor sleep. The brain regions important for emotional processing change in terms of their activity levels under conditions of sleep loss. One such study found the brain’s emotional center, the amygdala, to be 60% more reactive after 35 hours of wakefulness (Yoo et al. 2007). In addition, functional connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex (the part of our brain you can consider the “count to 10 before responding” part) and the amygdala was significantly decreased. To put it simply, such findings suggest our brain is highly emotional without the ability to put easily things in perspective, even in healthy individuals without any prior history of mood disorders.

The aforementioned study on Haitian earthquake survivors where 94% reported insomnia, also underscores the importance of sleep in preventing subsequent mental health disorders. Two years after the earthquake, 42% showed clinically significant levels of PTSD, and 22% showed symptoms of depression. Sleep disturbances were positively correlated with per traumatic distress (i.e., emotional reaction during and immediately after the event), PTSD, and symptoms of depression. The study on the Wenchuan’s earthquake survivors also found that poor sleep quality was significantly predictive of developing PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

SLEEP AS A MENTAL THERAPEUTIC

Besides studies highlighting the risk of sleep loss, there are also studies showing how a good night of sleep, or extra sleep (e.g. a nap) can boost our mental wellbeing. One such study found that a normal night of sleep basically “resets” the connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, leading to lowered emotional reactivity the next day (Van der Helm). Studies of naps have also found that after a nap, people report better mood and lower reactivity to previously exposed negative emotional facial expressions (Gujar et al 2010).

Given such findings, sleep can be regarded as a mental therapeutic or even “overnight therapy”, whether it’s stressful or normal times. Both the CDC and the WHO also mention sleep as one of the key things to prioritize when dealing with COVID-19-related stress “rest sufficiently, eat healthy foods, get physical activity and stay in contact with family and friends” (WHO and CDC).

SLEEP DURING COVID-19

Given the unique role sleep plays in maintaining emotional balance, it is worth looking at how COVID-19 poses both unique sleep challenges and sleep opportunities.

Sleep challenges range from the increased levels of stress previously discussed, to smaller challenges that are specific to working from home, a change that affects physical exercise, bright light, social interactions and our work/sleep environment.

- Intense working days: Employees working from home often experience an overlap between work and their personal life: e.g., difficulty setting boundaries, creating daily breaks, and managing some “distance” between work and personal life. A study done in 2017 by the United Nations International Labour Organization (ILO) including data from over 15 countries, found that though people were productive while working from home, it also brought risks of ‘longer working hours, higher work intensity and work-home interference’. Remote workers reported not only higher levels of stress, but also higher levels of insomnia (42% versus 29% of office workers).

- Exercise: Employees might get less exercise due to their walking or biking commute disappearing, walks around the office having vanished and sports clubs being closed. This is problematic for healthy sleep, as exercise has been found to boost sleep such as increasing our total sleep time and particularly deep sleep (for a review see Driver and Taylor, 2000). It is of note here to mention that studies have also found that people who sleep more or better are more inclined to exercise, another reason to prioritize sleep (2006).

- Light: It is critical for good sleep as well for our alertness levels during the day to be exposed to sufficient bright light: brightness levels that you get outside, which are much higher than light levels in an office or within a home environment. For 7 a lot of people, their work commute is the only time they spend significant time outside and not having this daily exposure to bright light can lead to a shift in their sleeping times (away from the optimal sleep time) or lowered quality sleep.

- Remote, alone and lonely: The lack of or reduction in social interaction can easily lead to increased feelings of loneliness. In a recent study amongst 1,900 remote workers, 22% reported that their biggest struggle with working remotely is loneliness, but keep in mind these are workers who were used to working from home and 43% of them worked remote only part of their working time. As mentioned earlier, loneliness has been found to lead to poor sleep.

- Sleep environment: Finally, for good sleep, it is recommended that the bedroom is used solely for sleep. However, some employees will likely have to use their bedroom as their home office space, which can significantly disrupt their sleep by bringing work stress into the bedroom and decreasing the “healthy” association we need between the bedroom and sleep.

Sleep opportunities are fortunately also present in these difficult times. The lack of travel, daily commute and “office face time” offer unique opportunities for employees to boost their sleep. Travel often means curtailed sleep or poor sleep quality for employees due to jet lag, poor sleep in unfamiliar places (e.g., hotel rooms), and early alarms due to early flights or late bedtimes due to late arrivals. Not having to commute any more means later alarms and potentially more time in the evening for more sleep.

We know from our own data at Shleep that many employees are chronically sleepdeprived - that is not getting the amount of sleep they need on a regular basis and building up what we call a “sleep debt” across a regular workweek. The special circumstances employees are in right now could offer a unique opportunity to “pay off” their built-up sleep debt and get back to a healthier and productive “sleep balance”. We have found that the level of sleep debt is directly correlated with both perceived stress levels as well as the performance at work; therefore focusing on ways to lower sleep debt will lead to not only better mental health, but also better to performance.

FORMAT CONSIDERATIONS FOR WELLBEING SOLUTIONS: DIGITAL, COMMUNITY AND PROGRAMMATIC

What sort of wellbeing solution delivery format requirements are important, given the COVID-19 crisis? You might have existing offerings that are obsolete (in-person events, facilities, and offerings available only in the office). With so many employees working from home and not coming into a common office space anymore, it is clear that wellbeing offerings need to be available digitally, so that employees can use them from home (or really from anywhere).

Another critical format element is the ability to create a sense of community within the wellbeing solution. Whether it is between colleagues who are team members and might work together on a daily basis or between colleagues who do not ever work together, both can serve an important role in ensuring employees feeling that they are part of a shared group in spite of being remote. It offers an opportunity to reconnect in a social way with a different focus. In our experience, it can be powerful to share personal experiences around a wellbeing topic with colleagues and to jointly problem-solve different solutions. It often creates a feeling of connection and accountability when setting goals and sticking to intentions.

Some in-person events and offerings, such as in-person training or a wellbeing talk, might still be able to take place digitally through a video call/webinar if they do not require everyone to be physically together in the same space. Such “live” events can help create a sense of community now that people are remote. Fortunately, many video tools offer the ability to create wonderfully dynamic sessions, with lots of back and forth, instead of a one-way “stream”. These events can also form the “kick-off” for a larger program or launch of a wellbeing offering. In our experience at Shleep, it is always critical to create momentum and buzz in an organization when you launch a new offering. Live events where you engage the community can offer a unique opportunity to create awareness explain your wellbeing solution and get employees excited about it.

As also the WHO reminds us, when thinking about your employees’ wellbeing during COVID-19, it is not a sprint, but a marathon. Besides wellbeing being digital and focused on creating community, it is important to think not in one-off solutions, but in programs and in longer-term coaching. This is of course always the case and not new for COVID-19. The main reason is that many wellbeing solutions are focused on behavior change and behavior change does not happen overnight. Simply creating a one-off awareness event can spark initial interest and motivation, but action tends to last for only a short time. To see results months later, employees should be supported through longer-term coaching programs that focus on small behavioral changes that lead to real habit change. With people already having multiple changes to contend with, they struggle to implement new healthy habits without support and guidance from experts.

Lastly, your wellbeing program should be flexible enough to take into account that employees’ needs change, be it in their personal life, at work, or during crises. In the initial outbreak and subsequent lockdown measures, our sleep experts across the globe reported that there was an increase in general issues with insomnia due to COVID-19 related worries, levels of stress because of the new work routine, and complaints of poor sleep quality.

HOW SHLEEP CAN HELP YOUR ORGANIZATION

At Shleep, we are focused on helping organizations improve employee wellbeing and performance through a digital sleep solution that has been designed by leading sleep and behavior change experts (all with a relevant PhD in the field).

Our solution is a combination of live (but remote) awareness events, 1:1 coaching with sleep experts, team-based tools and a long term individual coaching program. We create a sense of community between coworkers and within teams to leverage the power of peer-to-peer accountability when it comes to getting to real results.

Our team of experts is currently working hard to help as many organizations as possible during the current crisis, to ensure their workforce comes out stronger in the end. We are able to adapt quickly to the fast changing needs by providing 1:1 coaching with our sleep experts and providing science-backed advice relating to managing sleep, providing science-backed guidance on why sleep matters for immune health, how to manage sleep during times of change, as well as best practices for healthy remote working and energy management.

To receive more information on Shleep and how we can help to implement our solution into your wellbeing strategy at this time, please reach out to us at hello@shleep.com.

REFERENCES

- Harvard Health Publishing (2010). Mental health problems in the workplace.

- World Health Organization (2019). Mental health in the workplace

- World Health Organization (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during COVID-19 outbreak

- David M. Fergusson, PhD; L. John Horwood, MSc; Joseph M. Boden, PhD; et al (2014). Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort.

- Aon Hewitt, the National Business Group on Health and Kantar Futures (2017). Consumer Health Mindset Survey

- Els van der Helm, Matthew P. Walker (2009). Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain

- Judite Blanc, Tanya Spruill, Mark Butler, Georges Casimir, Girardin Jean-Louis (2019). Is resilience a protective factor for sleep disturbances among earthquake survivors?

- Suo Jiang, Zheng Yan, Pan Jing, Changjin Li, Tiansheng Zheng and Jincai He (2016). Relationships between sleep problems and psychiatric comorbidities among China's Wenchuan earthquake survivors remaining in temporary housing camps

- Eui-Joong Kim and JOel E. Dimsdale (2014). The effect of psychosocial stress on sleep: a review of polysomnographic evidence

- Reynolds CF, III, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, Houck PR, Schlernitzauer M, Pasternak RE, et al. (1993). Sleep after spousal bereavement: A study of recovery from stress. Biological ..Psychiatry. 34:791–797.

- Smith, S. S., Kozak, N. & Sullivan, K. A. (2012). An investigation of the relationship between subjective sleep quality, loneliness and mood in an Australian sample: can daily routine explain the links? Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 58, 166–171 and Tavernier, R. & Willoughby, T. (2014) Bidirectional associations between sleep (quality and duration) and psychosocial functioning across the university years. Dev. Psychol. 50, 674.

- Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Meyer, B., Lindman, L. & Istre, T. (2006). Daily activities and sleep quality in college students. Chronobiol. Int. 23, 623–637.

- Horne JA. Sleep function, with particular reference to sleep deprivation. Ann Clin Res. 1985;17(5):199–208.

- Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, Gillen KA, Powell JW, Ott GE, et al. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4–5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20(4):267–277.

- Zohar D, Tzischinsky O, Epstein R, Lavie P. The effects of sleep loss on medical residents’ emotional reactions to work events: a cognitive-energy model. Sleep. 2005;28(1):47–54.

- Eti Ben Simon, Matthew P. Walker (2018). Sleep loss causes social withdrawal and loneliness.

- Seung-Schik Yoo, Ninad Gujar, Peter Hu, Ferenc A. Jolesz, Matthew P. Walker (2007). The human emotional brain without sleep - a prefrontal amygdala disconnect.

- van der Helm E, Yao J, Dutt S, Rao V, Saletin JM, Walker MP. REM sleep depotentiates amygdala activity to previous emotional experiences. Curr Biol. 2011;21:2029–32.

- Kosuke Kaida, Masaya Takahashi, Yasumasa Otsuka (2007). A short nap and natural bright light exposure improve positive mood status.

- Gujar N, McDonald SA, Nishida M, Walker MP. A role for REM sleep in recalibrating the sensitivity of the human brain to specific emotions. Cereb Cortex 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Managing anxiety and stress.

- International Labour Organization (2017). New report highlights opportunities and challenges of expanding telework.

- Helen S. Driver, Sheila R. Taylor (2000). Exercise and sleep.

- Shawn D. Yungstedt, Christopher E Kline (2014). Epidemiology of exercise and sleep.

- Buffer and AngelList (2020). The 2020 state of remote work.

- C.M Morin, P.J Hauri, C. A Espie, A.J Spielman, D.J Buysse, R.R Bootzin (1999). Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review.

- UN News (2020). COVID-19: Mental health in the age of coronavirus