Cutting-edge technology and traditional vaulting from Segovia to Venice

As the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023 nears its end, Wesam Al Asali, IE School of Architecture and Design Professor, discusses a collaborative project involving IE University and other institutions at the European Cultural Centre.

On November 26, the 18th Venice Biennial of Architecture “The Laboratory of the Future” closes its doors and we take one last look at the Angelus Novus Vault, which serves as the entrance to the Time Space Existence group show, organized at Palazzo Mora by the European Cultural Centre around the theme of the climate emergency.

IE University’s researchers and students collaborated with Princeton University's Form Finding Lab, the architecture firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM), and the Universities of Bergamo and Salerno, to develop this self-balancing brick arch. Designed and built in just three months, using augmented-reality goggles, the project was, however, informed by previous know-how.

Earlier this year, researchers from IE University, Princeton University, and the University of Bergamo teamed to design innixAR, a vaulted pavilion made of unreinforced masonry. The project was constructed on the campus of IE University in Segovia as a shaded gathering spot for students and faculty members, as well as a tranquil meditation area.

We talk with IE School of Architecture and Design professor Wesam Al Asali about the two projects and their connections.

Aside from the fact that both projects share some team members, what are the key common threads between innixAR and Angelus Novus Vault?

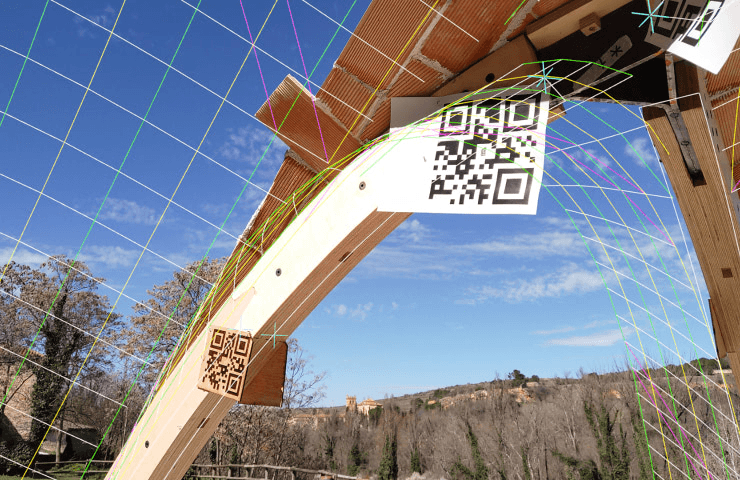

Both projects are part of the same exploration thread, focusing on the intersection between construction technology and traditional building craft. This exploration is a result of our research efforts under the "Structural Crafts" initiative, a collaborative with Professor Sigrid Adriaenssens, the director of the Form Finding Lab at Princeton University. In both projects, augmented reality was employed to guide the master builder during the construction of the vaulted structures. This approach raises several important questions about the feasibility of this intersection, its potential impact, and the time required for its practical implementation.

The experience gained from building innixAR in Segovia played a pivotal role in the Venice project. Even though the two projects have distinct designs, the construction technique remained consistent. Consequently, Salvador Gomis, the master builder for both structures, had the opportunity to work with augmented reality in different contexts, designs, and applications, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of its utility. Both innixAR and Angelus Novus Vault explore and present potential future applications of augmented reality in the field of masonry shell construction. This technology offers the potential for faster construction, simplified molds, and guidance systems, as well as training for novice builders. It's essential to highlight that the technology does not replace the expertise, skill, and dexterity of a master builder but rather engages in a dialogue with these invaluable qualities.

What are the applications and benefits of a mixed-reality construction approach?

Mixed-reality construction is a rapidly evolving industry with several key objectives. Firstly, it aims to facilitate well-informed construction practices, particularly when dealing with unconventional geometries or complex on-site techniques. Secondly, it seeks to enhance precision in construction and manual work. However, the most crucial objective is to eliminate the need for physical production of printed plans and layouts and instead facilitate direct communication between builders and designers right at the construction site.

In the context of the tile-vaulted pavilions we did, one significant advantage we observed was the elimination of physical guidework typically made using PVC or steel rod networks. We replaced these traditional guidework systems with digital alternatives by using Twinbuild software on Microsoft HoloLens, resulting in faster construction processes that were not hindered by substructures. This transition to digital guidework improved efficiency and productivity on the construction site.

Could you describe the design and construction processes for both projects and how tradition and advanced technology interact?

We adhered to age-old principles for constructing arches and domes, but we harnessed advanced computational tools to assist in shaping these structures. For example, the design of Angelus Novus was a collaborative effort involving designers at SOM and Carlo Olivieri as the structural engineer. It utilized a herringbone pattern to enhance the vault's construction without the need for traditional formwork. In the case of innixAR, the form-finding process was influenced by the constraints posed by tile vaulting craftsmanship. This method, developed by Rafael Pastrana and Robin Oval at the Form Finding Lab, was shaped through discussions with Salvador, the builder, who played an integral role in the project's design and decision-making from the outset.

The introduction of digital guidework and the use of HoloLens involved multiple iterations and mockups with the master builder before the pavilions' construction. A key consideration throughout this process was finding the right balance between providing the builder with detailed information and leaving room for his experienced judgment. This dynamic led to a "pattern-finding" process, wherein we introduced the geometric aspects of the shell but allowed the builder to determine the precise placement of individual bricks.

This approach challenged traditional hierarchies in architecture and construction, where plans are typically created for builders to execute, and architects and engineers subsequently review and approve the work. Instead, we discovered that successfully integrating technological advances into traditional construction relies on open and meaningful collaboration with craft communities.

Did you rely on local craft, materials, and organizations for innixAR? And what about those in Venice?

In Segovia, innixAR was constructed using locally sourced tiles readily available in the region. This was a straightforward process as tile vaulting is deeply ingrained in Spain's construction industry. In Venice, our team partnered with a factory that produced recycled bricks used for the vault's construction. While the tradition of tile vaults has historical roots in Italy, contemporary tile vault builders are more commonly found in Spain and Tunisia.

Salvador led the construction effort in collaboration with a local Italian construction company that provided essential infrastructure at the construction site, including formwork, and building equipment. This experience underscored the significance and potential of the tile vaulting craft in the future sustainable architecture within the Mediterranean region. We are continuing our work in Venice with plans for additional activities and workshops aimed at teaching tile vaulting in Italy.

Do students get involved in the design concept and project development of these projects and how do you think this might contribute to their education?

The involvement of students was mainly in the construction of innixAR. We capitalized on the presence of numerous experts and leaders in the field to conduct a workshop for students, focusing on the design and construction of tile vaults. This workshop encompassed teaching essential skills related to using computational methods for designing, form-finding, and 3D scanning vaults. Students have also practiced the craft of tile vaults and were engaged directly with multiple hands-on activities. Consequently, two student groups from IE University successfully designed and built small-scale structures during the workshop.

Additionally, students were introduced to the use of holograms in construction. Instead of utilizing HoloLens, they employed their mobile devices to guide them in building their structures, with assistance from Salvador. This experience provided them with practical insights into the innovative use of technology in construction.

Credits of Angelus Novus Vault. Researchers from: IE University - Wesam Al Asali; Princeton University - Sigrid Adriaenssens, Orsolya Gaspar, Robin Oval; University of Bergamo - Vittorio Paris; University of Salerno - Carlo Olivieri. Management: Sigrid Adriaenssens, Alessandro Beghini, Vittorio Paris; Design and Engineering: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) - Alessandro Beghini, Nathan Bluestone, Fernando Herrera, Grace Hsu, Juney Lee, Jassy Lin, Mark Sarkisian, Stephanie Tabb. Structural Engineering and Site Management: Carlo Olivieri. Construction: Bóveda tabicada & CERCAA - Salvador Gomis Aviño and Wesam Al Asali (vaulting); Taramelli srl (general contractor); JPF-Ducret SA (glulam beam foundation contractor); Terreal Italia srl - San Marco Pica (bricks)

Credits of InnixAR. Researchers from: IE University, Princeton University, and the University of Bergamo. Management: Wesam Al Asali, Sigrid Adriaenssens. Design team: Rafael Pastrana, Robin Oval, Edvard Bruun, Wesam Al Asali. Construction: Salvador Gomis Avino, Wesam Al Asali, Robin Oval, Rafael Pastrana, Vittorio Paris. Sponsors: Princeton University’s Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS), Cerámicas La Paloma