- Home

- We Are Law School

- News

- Regulating The Platform Economy: Why Digital Work Demands Digital Rights

Regulating the platform economy: why digital work demands digital rights

Professor Catherine Barnard used her keynote speech at the IE Law School event to call for a reimagining of labor law to match modern digital realities.

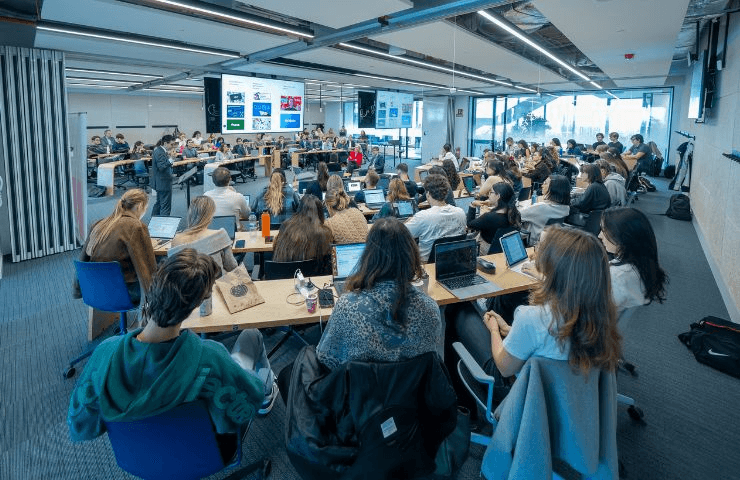

On October 23rd, IE Law School’s IE Center for European Studies organized a workshop on "European Regulation of Digital Work", in partnership with the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence for Law and Automation (Lawtomation).

Hosted at IE Tower, this event was sponsored by the Hablamos de Europa program under Spain’s Secretariat of State for the European Union, alongside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation.

The one-day symposium brought together legal experts from across Europe to discuss this pivotal subject in two informative panels. The first, focused on "Digital Transformation", was chaired by Associate Professor and Lawtomation Centre co-lead, Antonio Aloisi. Meanwhile, the second panel titled "Platforms and AI" was led by Marie-José Garot, Associate Professor at IE Law School and Director of the IE Center for European Studies.

Labor rights in the gig economy

The opening panel was headlined by keynote speaker Catherine Barnard, Professor of EU Law at the University of Cambridge and a renowned expert in employment and competition law. director of the Centre for European Legal Studies

In her presentation titled "Future of Work: New Forms of Regulation Addressing New Forms of Work," Barnard offered an analysis of how digitalization and algorithmic management are reshaping the legal landscape. "It’s important to have the correct status in order to trigger rights," she explained, discussing the need to reassess the traditional divide between employees and the self-employed within the context of modern platform-based work culture.

Barnard addressed the EU’s Platform Work Directive (PWD), assessing the new regulation’s extension of labor rights to those she referred to as the "falsely self-employed"—people working on gig economy platforms managed by algorithms. Under the PWD, she reflected, "For the first time, the self-employed are granted TAR rights: Transparency, Accountability and Review," a key shift in how labor protections are conceived in the digital age.

As Barnard explains, Chapter 3 of the PWD is among the most striking elements, being "legislation designed to control how businesses manage workers using algorithms." Though limited specifically to platform workers and not covering those in an Amazon warehouse monitored by wearable tech, for instance, she feels it’s undoubtedly a step in the right direction.

Barnard went on to explore emerging forms of digital labor, using the example of an influencer and arguing: "If a platform removes an influencer, it’s akin to dismissal." As such, Barnard says, "She may have a claim under the Digital Services Act—she should have some rights," pointing to the DSA as a source of protection offering a broader scope in certain circumstances than the PWD. Barnard concludes, "Work is being done differently today. We must assess how these new jobs should be protected. I feel there is room for that under the DSA."

Digital assets, AI and the future of work

David Martínez Saldaña, IE Law School Adjunct Professor and associate at Uría Menendez, then presented a talk exploring "The Transfer of Digital Undertakings" that challenged attendees to reconsider what constitutes a business asset in the digital era. "An app made available to a group of self-employed workers may be acting as their boss," he said. "So if you transfer an app, you are effectively transferring a business."

"The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Termination of Employment" was the subject matter of a talk by Magdalena Nogueira Guastavino, Full Professor of Labor and Social Security Law at the Autonomous University of Madrid. Her presentation examined the legal challenges posed by the growing use of AI in the workplace, particularly in relation to employment termination. She explored the circumstances under which replacing human workers with AI might be legally justified, and emphasized the need for legislative frameworks to evolve in order to safeguard workers against potential misuse and ensure fair treatment in increasingly automated labor environments.

She discussed the cases in which an implementation of AI to replace human workers could be justified, and how legislation must adapt to protect the workforce from potential abuses.

The second panel featured Adrián Todolí, Professor of Labor Law at the University of Valencia; Daniel Pérez del Prado, Associate Professor of Labor and Social Security Law at the Carlos III University of Madrid; and Anna Ginès i Fabrellas, Associate Professor of Labor Law and Director of the Institute for Labor Studies at Ramon Llull University and Esade.

These experts expanded on the regulatory and ethical implications of platform work and artificial intelligence, with Ginès i Fabrellas providing an in-depth examination of algorithm discrimination as applied to labor law. She presented a series of cases where biased data sets were found to have been used to train LLMs, exacerbating the societal challenges already plaguing marginalized groups. In response, she explained, legal frameworks must do more to mitigate the damage caused by biased algorithmic profiling.

The core theme running throughout the workshop was a consensus that digital transformation, and specifically artificial intelligence, demands an urgent reimagining of labor regulations. In that context, there is hope, as Professor Barnard concluded: "I feel that labor law is now beginning to expand its scope, moving away from a focus on subordination and dependency."