- Home

- Blue Talks

- Lee Newman: ‘leadership Is Paramount During Challenging Times’

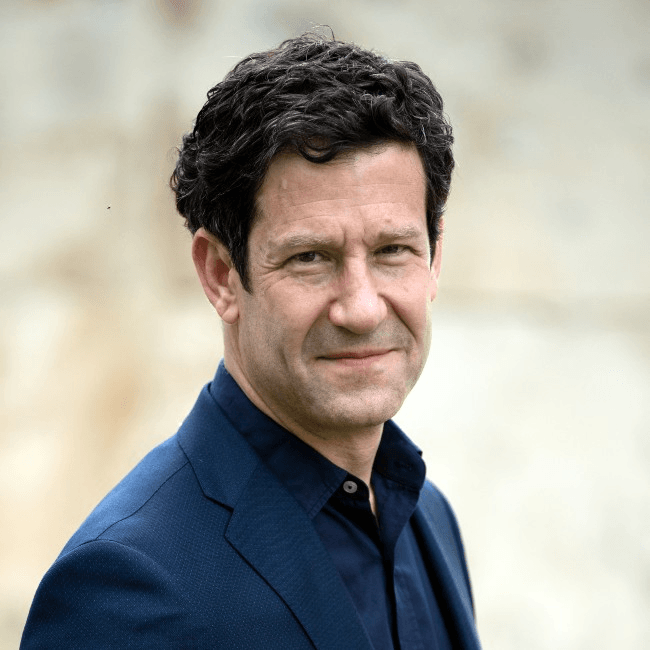

Lee Newman: ‘Leadership is paramount during challenging times’

The IE Business School Dean and Professor shares strategies for effective leadership in our rapidly changing world.

For Lee Newman, psychology and leadership are inseparable. Behavioral advantages, he believes, can help individuals and organizations consistently out-think and out-behave the competition. That belief was solidified as he weaved through a diverse range of academic disciplines — getting degrees in engineering, science and policy, an MBA, and a Ph.D. in cognitive psychology and computer science — as well as the private sector, where he worked for McKinsey & Company and founded two startups.

But his passion for reflection and investigation brought him back to academia. He has been a professor of Behavioral Science and Leadership at IE University since 2013 and is now the Dean of the IE Business School. In this interview, he shares some of the secret ingredients of great leadership and why it matters more than ever.

These last couple of years have been particularly turbulent. We’ve had the pandemic, significant economic issues and now a war in Europe. What do you think makes for a good organizational leader in turbulent and uncertain times such as these?

You could argue that the mandate for leadership is not very great when things are easy. In easy times, transactional management is enough. But leadership is paramount in challenging times. That’s when leaders are called upon and that’s when they should be thriving.

Great leadership is about being adaptable and flexible. But not just as an individual. It’s more about putting in place the organizational climate that allows others to thrive. In difficult times, people are stressed and they’re dealing with uncertainty so the role of a leader is to figure out the conditions that make others comfortable.

You have to reward failure because if you don’t, people won’t try new things. If they aren’t innovating and experimenting then your ability to deal with challenges is difficult. You’ll apply the status quo to address challenges. And that doesn’t work. But we know from science that when people are running on negative emotions, they are much less innovative and creative.

The way I think about it is that great leadership in many ways is about experience design. It’s about designing experiences for employees so that they are comfortable with uncertainty and scary changes. That’s not a trivial task, but it's one of the most important things you can do.

Trust in institutions and leaders has eroded in recent years. What do you think leaders can do to regain trust from society more broadly?

From a social standpoint, the way to gain trust is to do good things. I think people’s tolerance for showy promises is really low right now, so it’s less about spinning great narratives. People love stories, but they are also getting better and better at seeing through them. Instead, leaders need to walk the talk and demonstrate purpose-driven leadership.

Societies at large want to see purpose. That’s the word of the day. And it matters because the world wants to see companies do more than just survive and make a profit. The question becomes how you generate profit and what do you do with it. Of course, if you’re a public company you have a commitment to shareholders, but generating value beyond that is important. Organizations need to think about the impact of their processes, how they treat employers, suppliers and so on. Leaders need to show modern, responsible business practices in managing that ecosystem.

You’ve highlighted the importance of behavioral fitness in organizations, comparing it to training one’s body in a gym. Could you elaborate on that?

Here, I’m not referring to correcting deep weaknesses. It’s about fixing the little bad behaviors that we get in the habit of doing because of our personalities and the context in which we’re working. For instance, if someone is under pressure and is nervous about results, maybe he or she starts micromanaging everyone else. This is a habit that people get into. The more they do it, the more it's reinforced. It's like a muscle that you can make smaller with certain hacks.

Leaders can use this approach because it makes them more effective professionals and stops these little bad behaviors from tainting the climate. Having micromanagers, for example, creates a lack of autonomy in a team, and that’s not good. Behavioral fitness is identifying these issues and working on them one at a time.

What’s the best way to correct these bad habits?

The key is identifying the habit that has the biggest impact on your workplace. The best way to figure that out is to ask other people, which could be done through anonymous surveys. Then, there’s a process of going through the habits and identifying the triggers or cues. Ask: “What is triggering this behavior?” If your problem is that you’re a bad listener, maybe that’s because you want to participate in the conversation. Then, identify the specific behaviors. There are many forms of bad listening: interrupting, not paying attention, multitasking, and so on. Figure out your particular version. Then ask what reward you’re getting from the behavior. For example, maybe you interrupt people because it keeps you from getting bored and helps you stay motivated. Once this methodology has helped you identify that, you can replace the bad behavior with something that’s more productive and sustainable.

Why do you believe that positive psychology can be a game-changer for leadership and organizational performance?

Positive psychology is the science of performing at a high level. While clinical psychology is more about correcting negative behavior or problems to get back to normal functioning, positive psychology tries to get at the secret ingredients of high performance. One of those ingredients is the organizational climate. When we run on positive emotions, we’re more creative, innovative, deal with people more productively and look for common ground. When we run on negative emotions, it's the opposite. Our attention narrows, we focus on threats, we’re not as open-minded and we dwell on the negative.

Positive psychology in leadership is about thinking about how you can design experiences to create the conditions for your teams that produce more positive emotions and allow people to deal better with negative emotions. You're trying to change the ratio of what I call the blue pills and the red pills. The blue pills are positive and the red pills are negative. So, it’s about figuring out how to architect an environment where there are more blue pills than red pills. We know from science that when people have more blue than red pills, they perform better, think better and behave better.

As a Dean and Professor, how important do you think higher education is for forming leaders of the future?

It’s critical. I think education can provide key advantages for leaders. It gives everyone a wider and deeper platform on which they can work and behave. It’s about critical and creative thinking, which are skills that you can learn and sharpen. Not everyone naturally has all the skills required for leadership. In workplaces, people are often so busy that they don’t take time to learn these skills, reflect on what’s happened and why something did or did not work. Sure, people may implicitly get better at certain skills, but it’s not as deliberate. Yet, when you step out of that, even if it’s part-time, universities can create pivotal experiences because we facilitate and curate this idea of reflection and learning. Overall, I see us as curators and creators of game-changing moments.