Coming of age during the great recession and financial crisis of the past decade, new generations are questioning the economic recipes of the past century. As this report will show, many economists agree that policies based on production growth as measured by GDP are outdated. But what alternative model should we move toward?

CAN’T BUY ME LOVE: THE DEATH OF GDP?

IS HAPPINESS A HUMAN RIGHT?

COSTA RICA: HOW INVESTING IN PEOPLE BRINGS RICH REWARDS

POLITICS, LAW AND ECONOMICS TAKEAWAYS

Can’t buy me love: the death of GDP?

In mathematical terms, it is the sum of consumption, investment and government spending — plus exports, minus imports. It is practically impossible to read a news report on a country’s economy without it being cited. It seems incredibly important.

Yet for an increasing number of critics, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a symbol of many things that are wrong about our economic and political thinking. “GDP just cares about production of a number of shoes, but they could all be left-footed ones,” says Professor Diane Coyle, an economist and former adviser to the UK Treasury who has written extensively about GDP and the need to reform it.

The worst ravages of the financial and economic crises that started in 2007 may be over. But for the younger generations in today’s world, an economic model based purely on growing output is something they are neither familiar with, nor inclined to believe in.

Over half (56%) of respondents to the World Economic Forum’s 2015 global Shapers survey, who had an average age of 28, said economic and social inequality was the biggest issue facing the world today. What’s more, few young people in Western countries are optimistic about their own prospects as they are increasingly cut out of the wealth that is generated. A 2016 investigation by the Guardian newspaper found that people in Western societies born between 1985 and 1990 were earning less than their compatriots in other age brackets. The difference was as high as 19% in Italy, less than 10% in the United States and Germany, and 2% in the UK. Australia was the exception, according to data from the Luxembourg Income Study: Cross-National Data Center, with 20-somethings there earning 27% above the national average. In several of the countries studied, the growing proportion of the population who are retired enjoys a higher average income than the under-30s.

For some, the situation appears to be unsustainable.

“We’ve never had, since the dawn of capitalism really, this situation of a population that is aging so much and in some countries also shrinking. We just don’t know whether we can continue growing the economy in the same way we once did”Diane Coyle, Professor of Economics

New economic approaches will need new tools. What exactly is wrong with GDP, and how could it be reformed or replaced? In a 2009 study commissioned by France’s then-President Nicolas Sarkozy, two giants of modern economics, Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz, urged governments to adopt measurements that took into account overall human welfare.

The report by the Commission of the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress criticized the fact that the chief economic indicator on which policy decisions are often based could be happily rising at the same time as the disposable income of most people was falling and household indebtedness was soaring.

Likewise, the GDP method has no inbuilt sustainability factors. An oil spill could be a boon to GDP, prompting spending on a clean-up operation. Similarly, a foreign mining company arriving in a developing country to extract resources for exports might also boost GDP, but provide nothing but environmental destruction to the local economy. Another historical criticism of GDP is that it is sexist. Under the method, work done in the home, mainly by women, has no productivity value attached to it. A new and different problem is the amount of internet-based economic activity that escapes statistical capture as the collaborative economy becomes a staple of people’s lives.

“When the top 1% own more than everyone else combined, growing GDP simply hides the poverty within”Winnie Byanyima, Oxfam International

Also, GDP tells us nothing about the distribution of growth. Last year, Oxfam published figures purporting to show that the world’s top 1% owned the same as the other 99%.

Some questioned the methodology, but Oxfam International Executive Director Winnie Byanyima nevertheless still argued that the way the economy was organized required a complete overhaul. “When just 62 people have the same wealth as half the world’s population, where a country like Zambia can grow rapidly in GDP terms and yet can see increased levels of poverty, and where the 1% own more than everyone else combined, growing GDP simply hides the poverty within.”

What, then, could our alternative objectives be? In 2015, the United Nations unveiled its 17 Sustainable Development Goals, with “decent work and economic growth” at number eight. The UN urges governments, the private sector and civil society to work together to eradicate poverty, but our administrations and companies only tend to donate when they have profits and surpluses. What about a real change in philosophy?

“Happiness is a measure in which each person has a vote, but only one vote, whether rich or poor, sick or well, old or young”Richard Easterlin, Professor of Economics

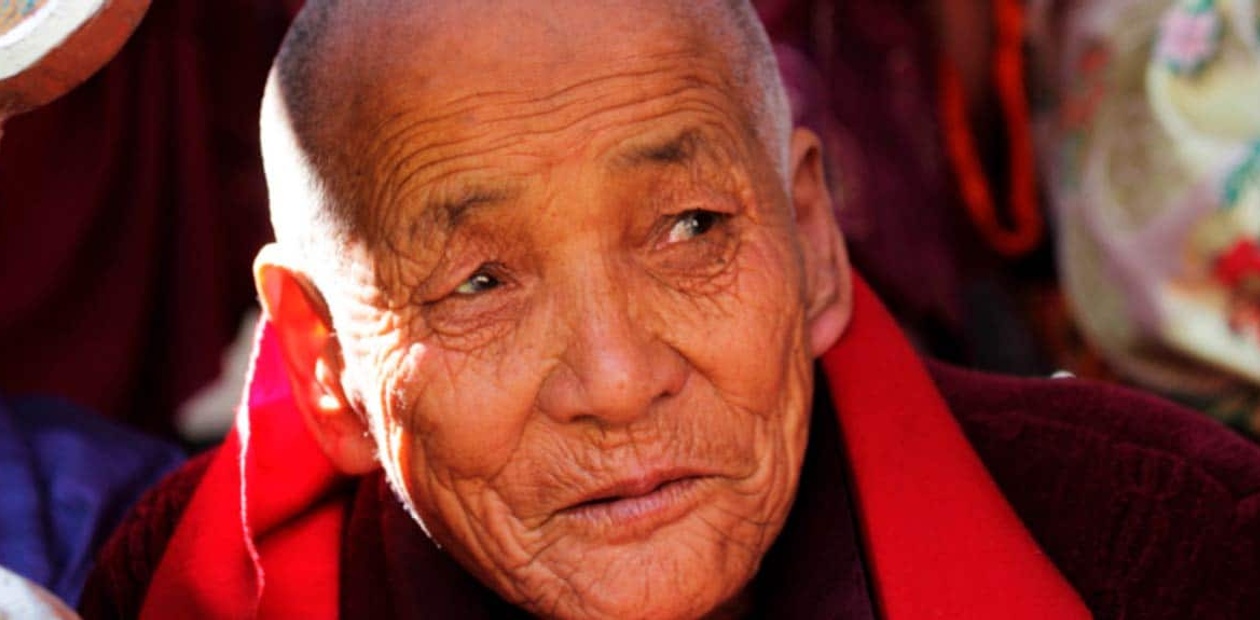

People often look east to the Himalayas for spiritual inspiration, and in this case it could perhaps come in the form of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (GNH) gauge. The kingdom first adopted its GNH policy in the 1970s, initially as part of efforts to resist foreign influences.

Now Bhutan has opened up — first to television, then the internet — and GNH is the subject of an extensive survey on wellbeing carried out in 2010 and again in 2015. Living standards are one category, but psychological wellbeing, satisfaction with the authorities, and the balance between work and rest are also included. Positive and negative answers accumulate to classify people as unhappy, narrowly happy, extensively happy or deeply happy. The 2015 survey showed a slight improvement among Bhutanese happiness rates compared to five years before, with 8.4% in the blissful top category, 35% extensively happy and 47.9 narrowly so. Those found to be unhappy fell from 10.4% to 8.8%.

A monk in Bhutan. Studies have shown that happiness leads to people living longer

Despite its esoteric origins, the idea of a happiness gauge is gaining traction. India and the UAE have created ministries of happiness in bids to balance the drive towards economic growth with greater harmony in people’s lifestyles. The economist Richard Easterlin has long argued that happiness should trump the measurement of economic output.

The Easterlin Paradox holds that while people with higher incomes are more likely to report greater happiness, increased happiness on a national level does not follow GDP growth.

Professor Easterlin gives four simple reasons why the measure of a society’s performance should be based on felicity, rather than economic output. First, happiness is a more comprehensive measure of wellbeing. “It takes into account a range of concerns while GDP is limited to one aspect of the economic side of life, the output of goods and services,” he wrote on the World Economic Forum website in 2016. He cited the example of China, where measured happiness declined in the two decades after 1990 when GDP per capita “doubled and then redoubled.”

“We just don’t know whether we can continue growing the economy in the same way we once did”Diane Coyle, Managing director of Enlightenment Economics

“Economic restructuring had led to a collapse of the labor market and dissolution of the social safety net, prompting urgent concerns about jobs, income security, family, and health — concerns not captured in GDP, but which significantly affect wellbeing,” Prof. Easterlin said.

His second point is that happiness is gauged by the people directly affected by it, not by “experts” reading selected data, and — point three — that it “is a measure with which people can personally identify. GDP is an abstraction that has little personal meaning for individuals.” Finally, he says GDH is more democratic. “Happiness is a measure in which each person has a vote, but only one vote, whether rich or poor, sick or well, old or young.”

Happiness seems to be growing in value by the day. It won’t be long before technology provides a solid mechanism with which to measure it.—

COMPARING MILLENNIALS INCOME TO THAT OF OTHER GENERATION, THE GUARDIAN

REPORT BY THE COMMISSION ON THE MEASUREMENT OF ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE AND SOCIAL PROGRESS (FRANCE)

OXFAM INEQUALITY REPORT CONTROVERSY

Is happiness a human right?

### In the consensus era of post-World War II politics — when even supposed right-wingers like Richard Nixon expanded the welfare state — we viewed governments as agents that brought improvements to the population at large. Now, in the era of global capitalism and the all-powerful individual, human rights have become the central tenet of political idealism and today’s leaders face the challenge of figuring out how to improve living standards and basic rights for the world’s poor without impinging on the individual freedoms of today’s wealthy consumers.

Amidst doubts over the institutional sphere’s capacity to faithfully represent common interests, people are grouping together in technology-based collaborative structures to achieve localized aims. But without the authority of national institutions, who can act as the ultimate guarantor of basic rights for all?

Better public policies

The rise of individual human rights has led some to demand that the right to happiness be enshrined in law as a basic condition. In 2014, philosophers and other critical thinkers gathered in Athens to launch a campaign calling on the European Union to recognize the right to happiness, citing the fact that over 60% of EU citizens — in particular a Greek population bearing the brunt of anti-austerity measures — did not feel happy or satisfied with life. According to the signatories of what is known as the Declaration of Pallini, the pursuit of happiness has been recognized as a “fundamental human goal and right” by everyone from Greek philosophers such as Aristotle and Epicurus to Thomas Jefferson.

Two years earlier Bhutan had managed to put contentment on the global agenda by persuading the UN General Assembly to adopt a resolution recognizing “happiness as a universal aspiration embodying the spirit of the Millennium Development Goals.” Member states were urged to help counter “unsustainable consumption patterns by elaborating measurements of happiness and economic wellbeing to better guide public policies.”

Happiness or freedom?

But while a right to Gross Domestic Happiness may sound like a wonderful idea, it feeds into the system of powerful states, under which a central authority provides what individuals need. If a right is guaranteed by, say, a constitution, it is something each citizen is entitled to demand. This therefore gives the state authority additional powers to fulfill its duty of meeting that demand.

For some, a focus on providing happiness would mean a world with fewer guarantees and directives on the way life should be organized. “I don’t think that happiness — in the modern sense — is at all a sensible goal,” the British political philosopher John Gray has said. “Because when happiness is the goal, the risk is that people become more cautious and less adventurous than they would be. Happiness is a myth of satisfaction. “Negative freedom is ‘true’ freedom because it best captures what makes freedom valuable, which is the opportunity it secures to live as you choose.”—

“I don’t think that happiness — in the modern sense — is at all a sensible goal”

John Gray, British political philosopher

Costa Rica: how investing in people brings rich rewards

### Money isn’t everything. Or at least that’s what the Social Progress Imperative aims to demonstrate with its annual index that ranks nations on how they meet the social and environmental needs of their citizens, rather than just in terms of economic prosperity.Lorem ipsum

But punching way above its economic weight in 28th position was Costa Rica.

In the three main sections of the Social Progress Index, the Central American nation placed 43rd in Basic Human Needs — not a bad result considering that, according to 2016 IMF data, it was 79th in the world in terms of GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity, just above Libya and Venezuela. It ranked 29th in the Foundations of Wellbeing bracket, which looks at education, health standards and environmental quality, and an exceptional 26th in the Opportunity ranking of personal rights, freedom, tolerance and access to higher education, ahead of far more developed countries such as Czech Republic and South Korea.

What has made Costa Rica such an outstanding exception …in a region that makes more headlines for its social problems. “Costa Rica introduced universal primary education at the end of the 19th century; it created a welfare state in the 1940s; it stopped spending on the military at pretty much the same time, so Costa Rica is doing well because it has spent a long time investing and building up this stock of social progress,” said the executive director of the Social Progress Imperative, Michael Green, on presenting the 2016 survey. “Our data shows that economic growth is generally a good thing. It’s just not the whole story, and especially when it comes to issues like tolerance, it does seem that just by getting richer, we are not going to make much progress in making our societies tolerant. What we need are other solutions, other policies, and that’s a challenge for rich and poor countries.”

“Costa Rica is doing well because it has spent a long time investing and building up this stock of social progress”Michael Green, Executive director of the Social Progress Imperative

The days of Costa Rica being best known for its pineapples are numbered. Far more important for the country’s continuing development are its four technology clusters, which support 287 companies and employ almost 78,000 in a country of less than five million people, according to 2015 figures from the CINDE development board.—

LESSONS FROM LATIN AMERICA. INNOVATIONS IN POLITICS, CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT

COSTA RICA

COSTA RICA

- 79in GDP per capita

- 28in Social Progress Index

POLITICS, LAW AND ECONOMICS TAKEAWAYS

POLITICS, LAW AND ECONOMICS TAKEAWAYS

GDP WAS NEVER A PERFECT MEASUREMENT AND SHOULD BE SEEN AS A PRODUCT OF ITS TIME

TECHNOLOGY MUST BE HARNESSED TO UNDERSTAND NEW ECONOMIC REALITY

21ST-CENTURY INSTITUTIONS ARE BEGINNING TO UNDERSTAND THE IMPORTANCE OF PERSONAL WELLBEING

NEW GENERATIONS WILL HAVE TO ENGAGE WITH EXISTING INSTITUTIONS AND MAKE THEM EVOLVE TO DEAL WITH GLOBAL ISSUES

Further reading

- GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History (Princeton University Press, 2014), by Diane Coyle

- Straw Dogs: Thoughts On Humans And Other Animals, by John Gray

- A Splendid Isolation: Lessons on Happiness from the Kingdom of Bhutan, by Madeline Drexler

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only. Some information has been compiled by third party sources that we consider to be reliable. However, we do not guarantee and are not responsible for the accuracy of such. The views of third parties set out in this publication are not necessarily the views of IE University and they should be seen in the context of the time they were made.

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?