What is human computation?

They say two heads are better than one, but what about seven billion heads plus technology?

When machines meet the human brain, what happens?

Human computation combines the power of information processing systems and humans to solve problems. It is a broad concept and an emerging field of study; at its most general level, it involves interconnected humans and machines processing information as a single system.

One problem it has already solved is: how can we create a quality encyclopedia that is completely free and comes in hundreds of languages? Through linking technology (the internet, computers or phones), the entire internet-using population and the clear goal of spreading knowledge, the online encyclopedia Wikipedia was born.

This innovative approach is also excellent for analyzing vast sums of information. In today’s world, data are being created faster than ever — enough to overwhelm any individual or small group. And despite the latest advances, machines still do not have the ability to understand abstract concepts, identify unclear images, analyze speech or label messy, qualitative data nearly as well as humans.

But technology can help break down the giant data sets into tinier tasks, analyze what it can, and send out the other tasks to the millions of people sitting at their computers, who are then able to perform a fraction of the total work with relative ease. That information can then be stored, organized and shared through joint techno-human effort.

“Technology is a path and not a goal of its own. It is nothing if not an enabler that will help us increase the connections between people and resources,” says Borja González del Regueral, Vice Dean of the IE School of Human Sciences and Technology.

Another important concept in human computation is that there is wisdom in numbers. Although one expert may be able to accurately analyze information, research and real-world experience has proven that when you combine answers from many non-experts into a single best answer, the non-specialized analysis is often better than that of the single expert. Democracy, the system of government that has thrived throughout human civilization, is based on a similar principal.

“The big change started with the boom of the telecoms industry and internet. That created the possibility of being connected all the time”Teresa Ramos, Director of the Bachelor in Information Systems Management at IE University.

Sometimes, even though a program or platform was not engineered to address a certain question, important data, produced by humans, also emerge in a more spontaneous fashion. And that data can now be stored and analyzed thanks to technology. Although a news article may be posted on social media just to be shared, the human input that comes along via ‘likes’, emojis or comments can provide insights about human behavior and also about the article, such as whether or not it is interesting.—

The human brain is widely considered to be the most sophisticated information processor in the world. With 1010 neurons, communicating in parallel over a network of 1015 dendritic connections, not even a billion-dollar AI program can yet rival the powers that reside in your head.

The merging of real and artificial intelligence

Although human computation could seem like the opposite of artificial intelligence (AI), the two sciences are closely related. In fact, human computation is often seen as a synergistic branch on the AI tree. “When we combine AI with human intelligence, we are taking the best of both worlds. AI is able to compute and learn from data at a higher speed than humans, but humans are the ones that provide the context,” says González del Regueral.

In fact, data produced through human computation are often used to create AI training material. All the data produced by crowds of people can be, and increasingly are, fed into machine learning algorithms.

“We don’t want to waste people’s time, so if you can do it with a computer, let’s do it with a computer,” says Grant Miller, community manager of Zooniverse, the world’s largest citizen science platform that calls on digital volunteers to help with scientific research. In the near future, he adds, science will be producing data sets so large that even millions of people working together won’t be able to analyze all the information.

“We can train computers now to do what humans could do 10 years ago, but more complex tasks continue to come forth,” he says.

“The more data available, the more complex it gets, so the machines are always lagging slightly behind”Grant Miller, Community manager of Zooniverse

By combining the technologies of machine learning, global connectivity and artificial intelligence with human intelligence, some experts even predict that we could end up with a “super-human intelligence,” capable of tackling some of the world’s most complex problems.—

WHEN THE CROWD GETS IT RIGHT

WHEN THE CROWD GETS IT RIGHT

Although not a fan of masses himself, controversial scientist Sir Francis Galton was one of the first to demonstrate the wisdom of crowds. He set up an experiment in which he collected guesses from random individuals at a popular fair regarding the weight of an ox. To his surprise, the average group answer was only one percentage point off the correct mark and was closer than any individual guess. This obtained collective intelligence is a fundamental principle behind human computation.

The collective PhD: how citizen science is changing research

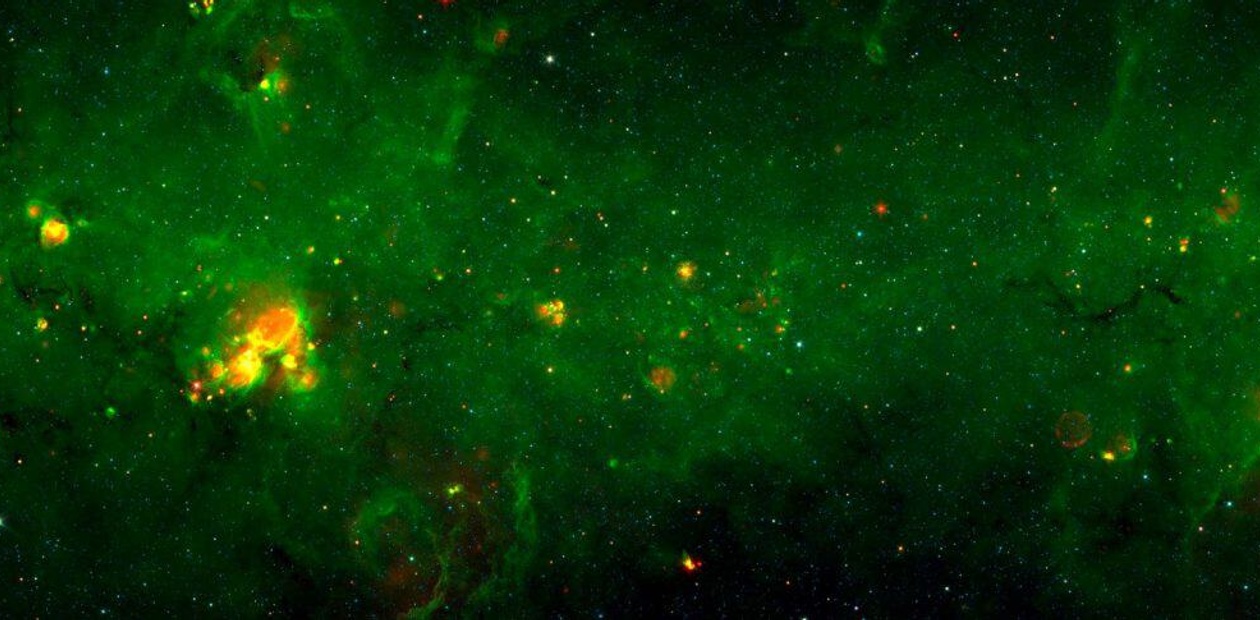

Zooniverse, the world’s largest platform for citizen science, all began when Kevin Schawinski needed a pint. It was 2007 and the young researcher in astrophysics had a theory that stars could be formed in elliptical galaxies, as well as younger ones. And he was in luck, because the Sloan Digital Sky Survey had collected images of millions of galaxies that he could look through to find patterns and prove his untested theory.

But because computers were unable to detect the patterns, he found himself working 12-hour shifts for seven days straight. In that time, he managed to characterize 50,000 galaxies, but even at that rate, it would still take him years of work to finish it all.

That’s when he called his friend Chris Lintott to meet at the pub. After some complaining and brainstorming, they came up with the idea (partially inspired by NASA) to ask the general public for help with identifying the images, a task that required little expertise but many man-hours.

A few weeks later and they had created GalaxyZoo, the predecessor of Zooniverse. And after only 24 hours of having the website online and some media attention, Schawinski’s project was receiving more classifications in one hour from volunteers than in one of Schawinski’s miserable weeks as single researcher.

WORLD IN FIGURES

WORLD IN FIGURES

The incredible power of human cooperation

- 7.5 BILLIONPopulation of planet Earth in 2017

- 3.7 BILLIONNumber of people who are connected to the internet in 2017

- 1 MILLION YEARSThe amount of time people had spent playing Angry Birds by 2015. With the gamification of research, similar amounts of time could be spent solving humanity's biggest problems.

- 20:01Number of single individual answers to produce a single lab-quality answer for the EyesOnALZ project. (Although a new algorithm has been validated that aims to bring the ratio down to 7:1)

“PhD students are delighted; it’s the contrary to the fear that they’ll lose their jobs. Before, a student was limited by the amount of information they could process themselves, but citizen science has opened them up to fields of research that just weren’t possible in the past,” says Miller. For nonexperts, platforms like these can give people the thrills of participating in scientific discovery and the satisfaction of helping.

For example, during the GalaxyZoo project a Dutch school teacher, Hanny van Arkel, actually discovered an astronomical object that had never been seen before. The objects, of which more have been found (including some by other citizen scientists), have been named in her honor — Hanny’s Voorwerp (Hanny’s object).

Since its astronomy-specific inception, Zooniverse has morphed into an open platform from which anyone is able to request help from its online volunteer army. Other popular and varied projects include spotting penguins, transcribing old manuscripts and looking for the ninth planet in the solar system.

“Before, a student was limited by the amount of information they could process themselves, but citizen science has opened them up to fields of research that just weren’t possible in the past”Grant Miller, Community Manager of Zooniverse

“If you have a lot of data that are worthwhile to analyze, you can ask people to help. But don’t take it lightly — these are real people sacrificing their time for you. But if you can show results and provide information, they’ll stick around,” says Miller.

And while Zooniverse is just one platform, human computation is merging with citizen science in hundreds of different projects. Some scientific research is even packaged in the format of an addictive game so that players also make a contribution to knowledge.—

TAKE PART IN CUTTING-EDGE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH AT ZOONIVERSE

ZOONIVERSE PUBLICATIONS TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE ZOONIVERSE CONCEPT CHECK OUT THE “META” CATEGORY

An image from Zooniverse’s Milky Way Project, in which the main goal is to identify stellar-wind bubbles within the galaxy.

Joining minds to bridge the divide

Pietro Michelucci is a pioneer in the field of human computation. As the director of the Human Computation Institute, he has worked ceaselessly to raise awareness and provoke conversation around the emerging science. He also runs the EyesonALZ citizen science project that aims to improve the existing knowledge and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease by using volunteers to watch film of human and mouse brains to spot stalled blood vessels.

What motivates your volunteers to get involved?

The folks who get involved are doing it because they care about the end goal – they want Alzheimer’s to go away. It’s a cruel disease and today there are no effective treatments, so a lot of folks feel helpless. This is an opportunity for them to personally make a difference in a disease, for their loved ones or even possibly for themselves in the future. One of the cool things about human computation is that it rebalances the playing field. There’s something dangerous about the idea that one person in the village is suddenly more powerful than everyone else combined, just because they have a certain technology. But because in human computation the system’s abilities and powers are related to the size of the crowd, then the bigger the crowd is, the stronger the system is. So this kind of reestablishes that balance. It starts to make state-based or collective actors more powerful than individuals once again.

What about the problem that if you break up a task into so many small parts or microtasks, people are not necessarily aware that they might be doing something harmful?

There’s the risk of that. In any online or participatory system, you could have a bad actor who creates a system and tricks people, saying you can have fun playing this free game and you don’t realize that you’re helping a hacker decrypt a code that would give them access to a million credit card numbers. I think human computation scientists need to develop a code of ethics in building systems; this is no different than lot of things in human history where we have to define what we condone.

“Human computation rebalances the playing field because the bigger the crowd is, the stronger the system”Pietro Michelucci, Director of the Human Computation Institute

What can we learn from understanding the behavior of insects?

Here’s an example of collective behavior that allows ants to survive: there’s a species that forms a raft in order to cross rivers. They all connect to each other and they pile on top of each other to form a raft. That allows them to safely cross a river. There’s a survival advantage to this, so they can escape or find food. No single ant fully understands what a raft is or how it works, but it’s programmed into their DNA, as far as we understand. The raft is an emergent property of this collective behavior.

A lot of experts have been warning about the dangers of AI. What do you think about this and do you think human computation could make it safer?

By inserting humans into the system, we have an opportunity to give humans control at the right level. When lives are on the line or when a decision could have consequences for human wellbeing, you’d want to make sure the final decision was going to a human. And you also need a kill switch. But at the same time, we have to keep in the back of our minds that we have a rich and unfortunate history of humans making poor decisions. So even if we’ve solved the risks of AI making bad decisions, we still haven’t solved the problem of humans making poor ones. I believe that over time AI will usurp existing jobs. Yet I think with human computation there will be new jobs, and those jobs will be more interesting to people because they’ll tap into the abilities that humans have, like creativity, abstraction and the application of knowledge.—

PLAY THE STALL CATCHERS GAME AND HELP WITH ALZHEIMER’S RESEARCH

WHAT SEPARATES A WISE CROWD FROM A FOOLISH ONE?

WHAT SEPARATES A WISE CROWD FROM A FOOLISH ONE?

Not all crowds are wise — consider mobs, “group think,” stampedes or stock market crashes. But, as demonstrated by human computation, sometimes crowds are faster, more reliable and more objective than even individual experts. But what makes some masses smart and some completely irrational? According to James Surowiecki’s book, The Wisdom of Crowds, when these four criteria are met, collective intelligence emerges.

KEY CRITERIA

Key criteria to separate wise crowds from irrational ones

DIVERSITY OF OPINION

The groups should consist of people with unique opinions, knowledge and backgrounds. Often the best decisions are products of disagreement and compromise.

INDEPENDENCE

People should be independent and their opinions should not be influenced by the other group members. Too much communication can lead to “group think” which can result in massive errors.

DECENTRALIZATION

Members of the group are able to draw from local knowledge and specialized information.

AGGREGATION

A smart mechanism is needed to properly weigh and combine the various answers into one. Here’s where human computational algorithms come in, to calculate the best way to determine the most appropriate answers.

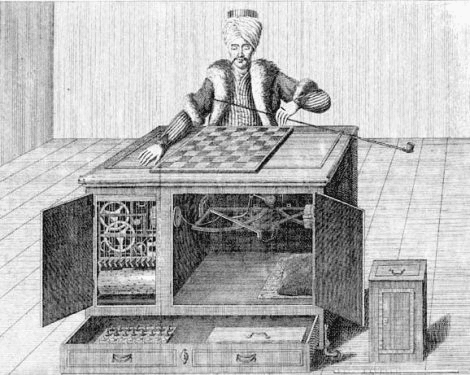

The man in the machine

The Mechanical Turk was a chess-playing machine constructed in Germany in 1770. Hundreds of years before computers, the inanimate man, dressed as a traditional sorcerer and stuffed with cogs and clockwork machinery, traveled through America and Europe, beating nearly all of its opponents, including Napoleon Bonaparte.

But no, this primitive robot (or automaton, as it was called at the time), did not travel from the future to the late 18th century. The whole thing was actually an elaborate hoax. While it looked like the machine was exceptionally good at chess, there was actually a human chess master hiding inside, secretly controlling the Turk’s movements from within the machine.

Many people in the crowdsourcing world joke that like the Turk, the concept of human computation is a form of “artificial artificial intelligence.” This is because in some instances, it may seem like AI is solving a problem or analyzing data, but behind the machines lie real people with their non-artificial intelligence.

In the 21st century the Mechanical Turk has made a resurgence, but this time it is managed by Amazon. Amazon Mechanical Turk is a crowdsourcing and human computation platform that solves problems for different organizations. It breaks problems into micro-tasks and pays workers small amounts of money to do such chores as identifying images. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO, is credited with coming up with the idea, and the platform was launched in 2005. Since then, the idea of crowdsourcing work has become increasingly popular, either to solve problems directly or to teach machines how to do it.

“There’s maybe anywhere from one million to a couple million people working for us”Will Plescow, Accounts manager at Crowdflower

LISTEN: NPR’S PLANET MONEY PODCAST: THE PEOPLE INSIDE YOUR MACHINE

SEE WHAT IT IS LIKE TO BE OR WORK WITH A MODERN DAY MECHANICAL TURK

INFORMATION SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT TAKEAWAYS

INFORMATION SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT TAKEAWAYS

BUSINESSES AND ORGANIZATIONS CAN TAP INTO THE POWER OF CROWDS TO SOLVE PROBLEMS

HUMAN COMPUTATION CAN EMPOWER PEOPLE TO PARTICIPATE IN GROUND-BREAKING RESEARCH

WHEN PEOPLE COME TOGETHER ONLINE, THEY ARE CAPABLE OF HERCULEAN TASKS

MILLIONS OF HUMANS ARE TEACHING AI THROUGH TRAINING DATA SETS

Further reading

Online

- The power of crowds by Pietro Michelucci and Janis L. Dickinson

- Human Computation. Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning by Edith Law and Luis von Ahn

- Citizen CyberScience – New Directions and Opportunities for Human Computation by Greg Newman

- Polymath Stephen Wolfram Defends His Computational Theory of Everything by John Horgan

- Human Computation and Convergence by Pietro Michelucci

Offline

- The Handbook of Human Computation by Pietro Michelucci

- Human Computation by Edith Law and Luis von Ahn

- The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century ChessPlaying Machine by Tom Standage

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only. Some information has been compiled by third party sources that we consider to be reliable. However, we do not guarantee and are not responsible for the accuracy of such. The views of third parties set out in this publication are not necessarily the views of IE University and they should be seen in the context of the time they were made.

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?