Technology is changing the way that legal advice, services and products are provided with law firms facing challenges and opportunities in equal measure. This report will examine how artificial intelligence and the internet are transforming the sector, and ask what the future holds for human lawyers.

ROBOT LAWYERS — ARE THEY THE FUTURE?

JOBS AT RISK OF BEING AUTOMATED

ROBOT LAWYERS AND CHATBOTS: DISRUPTIVE LEGAL TECHNOLOGY

THE CASE FOR VIRTUAL REALITY

Robot lawyers — are they the future?

Whether it’s Joaquin Phoenix’s lonely divorcee falling in love with his operating system, Samantha, (played by Scarlett Johansson) in the film Her, IBM’s chess-playing computer, Deep Blue, which can humble grandmasters, or Google’s AlphaGo beating international champion Lee Sedol at the ancient Chinese board game Go, artificial intelligence (AI) is everywhere and rapidly becoming a game-changer in many industries. But what is it and what does it mean for law and future lawyers? Will the predictions of Professor Richard Susskind, whose books foretells The End of Lawyers, come true or are their limits on how far technology can go to replace human practitioners?

Richard Tromans, adviser on legal AI technology and author of the Artificial Lawyer website, demystifies the technology. He explains that AI is a “family of technologies,” used in many fields across many sectors — from self-driving cars to image recognition systems and mechanical robotics, and now increasingly in the legal profession. Essentially, it is the theory and development of computer systems that perform tasks that normally require human intelligence.

The types of AI used in law, says Tromans, are primarily related to text, referred to as “natural language,” as opposed to programming commands, and the software developed to read the text is called “natural language processing” or NLP.

AI uses algorithms to read and analyze legal documents. For the uninitiated, an algorithm is basically just a list of rules to follow in order to solve a problem. Most AI systems, adds Tromans, have machine-learning capabilities that enable them to improve. “AI is not a robot, it’s not frightening and it does not spell the end of the legal profession. It is a very important development, but it’s a positive change that lawyers should embrace.”

“AI is not a robot, it’s not frightening and it does not spell the end of the legal profession. It is a very important development, but it’s a positive change that lawyers should embrace”Richard Tromans, author of the Artificial Lawyer website

JOBS AT RISK OF BEING AUTOMATED

JOBS AT RISK OF BEING AUTOMATED

Lawyers were asked: Can you envision a law-focused artificial intelligence replacing any of the following in the next five to ten years?

PARALEGALS

47%

FIRST-YEAR ASSOCIATES

35%

TWO- TO THREE-YEAR ASSOCIATES

19.2%

FOUR- TO SIX-YEAR ASSOCIATES

6.4%

SERVICE PARTNERS

13.5%

YES, BUT NOT IN FIVE TO TEN YEARS

38%

COMPUTERS WILL NEVER REPLACE HUMAN PRACTITIONERS

20.3%

So, what is all the fuss about?’

Tromans answers: “Law is text — contracts, legislation, rulings, agreements, skeleton arguments, patents — everything is text. Anywhere there’s text you can use legal AI.” If you have a piece of software that can read, analyze and report on an entire document in a couple of minutes, instead of hours, it immediately replaces the work of many paralegals or junior lawyers, changing the way law firms have traditionally operated. “AI increases the speed by a factor of 1,000. I’ve seen a 40-page complex real estate document digested and analyzed in 30 seconds,” says Tromans. “Machines don’t get tired, ill or take days off. Plus, they can work in parallel and read more than one thing at a time. It is the equivalent of an entire building of lawyers, working at a speed that they would be incapable of, and more accurately than a human.”

Aside from reading documents and performing much of the tedious, but essential, due diligence work done by commercial lawyers, John Flood, professor of law and society at Griffith University, Australia, says AI can be used for compliance and, more interestingly, to determine the chances of success by assessing whether it is worth bringing a case in the first place. Professor Flood explains that programs can examine past cases and judgments on the same issues and look at the judges and lawyers involved to give a good prediction of the likely outcome.

The judicial decisions of the European Court of Human Rights have been predicted to 79% accuracy using an AI method developed by researchers at University College London, the University of Sheffield and the University of Pennsylvania in which the software analyzed the information and made its own judicial decision.

The AI ‘judge’ algorithm examined English-language data sets for 584 cases relating to torture and degrading treatment, fair trials and privacy, reaching the same verdicts as judges at the European Court of Human Rights in almost four in five cases.

The Discovery Analytics Centre at Virginia Tech has also come up with a system to model the US Supreme Court using computer-based machine learning. The team has devised a data-driven framework that learns justices’ judicial preferences. It can be used to answer questions about the justices’ voting behavior, for example: how will the justices vote in a case about a particular topic? Which coalitions are likely to become relevant? Who is likely to be the swing justice in a given case or term? The model created a reasonably accurate assessment of justices’ views on issues, predicted their alignments on cases and identified who might be a swing vote.

- 584cases analyzed from the European Court of Human Rights’ files

- 461times an AI ‘judge’ ruled correctly

So will AI ever remove the need for lawyers altogether?

Chrissie Lightfoot, futurist, co-founder of Robot Lawyer LISA and author of the Naked Lawyer series of books, says not entirely: “Currently cognitive computing and most forms of AI require lots of data, so the service is limited to the machine pool of information and its quality and depth.”

Lightfoot continues: “Effectively, the quality of the output will be determined by the quality of the input. It is then limited by the requirement for someone, such as a lawyer, to reason and judge the output, based on human experience, knowledge and talent.”

But, while IT systems can currently only support lawyers, Lightfoot reckons that as machines become more intelligent, they may replace lawyers in some instances.

“Technology is limited by the requirement for someone to reason and judge the output, based on human experience, knowledge and talent”

Chrissie Lightfoot, Naked Lawyer Author

Professor Flood disagrees, saying there will always remain a need for human judgment in the legal process. AI, he says, works most effectively when used in conjunction with human lawyers. His point is demonstrated by a report, Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence, from the US committee of the National Science and Technology Council.

The study focused on a scientific, rather than legal use. Given images of lymph node cells, and asked to determine whether or not the cells contained cancer, an AI-based approach had a 7.5% error rate, where a human pathologist had a 3.5% error rate. But when you combined the two, using both AI and human input, the error rate lowered to 0.5%, representing an 85% reduction in error.

While AI may reduce the number of lawyers required for a particular task and alter the nature of some of the work done by lawyers, law students of the future can rest assured that they can still have a legal career ahead of them — but perhaps partnership with a machine.—

ROBOT LAWYERS AND CHATBOTS: DISRUPTIVE LEGAL TECHNOLOGY

ROBOT LAWYERS AND CHATBOTS: DISRUPTIVE LEGAL TECHNOLOGY

AI is the single most disruptive technology for the law. Investment and the momentum of technological developments are picking up speed. Products available range from those designed to help law firms work more efficiently to those enabling members of the public to sort out their legal problems themselves. So let’s have a look at what’s out there — here’s a sample from around the globe.

ROSS

ROSS has been hailed as the world’s first artificially intelligent lawyer. Built on IBM’s Watson (a computer system capable of answering questions posed in natural language), it is designed to understand language and provide answers to legal questions, by reading and analyzing an entire body of law on a subject, including legislation and judgments. It will also keep track of legal developments in the area. Lawyers still have to tell it the law in the first place, and will still be required to provide the advice to the client based on ROSS’s answer.

RAVN AND KIRA

Both are sophisticated document search algorithms for carrying out due diligence before transactions. They are quicker, cheaper and more efficient and precise than a paralegal or junior lawyer, and will remove a lot of the tedious work that is the bread and butter of young lawyers.

LAWGEEX

Founded in 2014 by international lawyer Noory Bechor and leading AI expert Ilan Admon, it is an online tool that uses artificial intelligence technology to provide fast feedback on contracts. It combines machinelearning algorithms, text analytics and the knowledge of expert lawyers to deliver indepth contract reviews efficiently and quickly. It will flag up unusual, problematic, or missing clauses and provides a report in plain English.

LISA

Lisa, or legal intelligence support assistant, is an app designed to meet the legal needs of small businesses and also encourage them to take legal advice from a real lawyer where necessary. Developed by AI Tech Support — a joint venture between a niche London corporate law firm Duthie & Co, and Chrissie Lightfoot, a futurist and legal consultant — Lisa is being offered free to small businesses.

DONOTPAY

An artificial-intelligence lawyer chatbot, designed by 19-year-old creator, London-born Stanford University student Joshua Browder. The free service helps users contest parking tickets. Asking users a series of simple questions, it works out whether an appeal is possible, and then guides users through the appeals process. It has helped more than 160,000 motorists in London and New York, saving them millions of dollars. It can also file compensation claims for delayed or cancelled flights.

AILIRA

The Artificially Intelligent Legal Information Research Assistant mixes chatbot and search. Created by a tax lawyer in Adelaide, Ailira automates legal research in relation to Australian federal tax law. You ask her a natural language question and she understands and looks for an answer that matches.

For centuries, learning and practicing law has relied heavily upon carefully parsing myriad statutes and examples of jurisprudence in large tomes to find the solution to any given legal question. But that is all beginning to change as artificial intelligence accelerates the perusal process and other forms of digital reality become available to law practitioners and students.

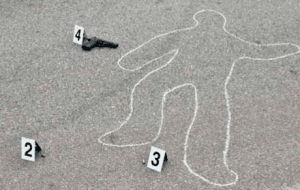

Many former law students in Britain, the United States and other countries will remember lectures about how the deliberate committal of certain crimes needs to be proved by establishing the actus reus (guilty act) in conjunction with the mens rea (guilty mind). But how do you effectively do that in concrete circumstances?

Some law schools are turning to virtual reality (VR) to immerse students in potential crime scenes so they themselves can decide whether the established facts of the case match with the evidence requirements to prove a given offense. Is the way the accused parked his car an indication of an intent to launch an attack or a robbery? Look and see. How plausible is it that a witness could not distinguish between her roommate and an intruder at that time of night? Judge for yourself.

As well as VR, augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR) technologies can be combined to enhance the vision and, ultimately, the potential wisdom of legal actors.

“Imagine judges and juries wearing VR/AR/MR devices to immediately transport them to a crime scene so they can deeply view, inspect and review pieces of evidence during a trial”Dennis Garcia, assistant general counsel at Microsoft Corporation.

“When teams use VR/AR/MR, they can interact with each other in virtual spaces or virtual ‘warrooms’ to collaborate with each other without having to be all together in one physical location,” Garcia continues. “Such use scenarios can be very compelling when lawyers and business clients based in locations across the globe need to closely connect with each other on matters where time is of the essence, such as sensitive contract negotiations, litigation, mergers and acquisitions, crisis management, and so on.”

What happens in VR stays in VR?

As well as potentially assisting lawyers and judges, the use of virtual technology also brings with it certain vexed legal issues that will need to be resolved. What about offenses caused or injuries inflicted between individuals in a virtual environment? Yes, the injured party can switch off or remove their VR headset, but is it right to accept that any offense is just the rough and tumble of a gaming environment and no harm is done? Actual law on such situations is scarce, but in the not-too-distant future we may look back on that gulf as a primitive state of affairs.

VR and other technologies can help the criminal lawyer take mental steps backward to gain a clearer picture of the facts.

Virtual dispute cases have already erupted into real-world courts, with varying results. One of the most notorious instances was the 2008 battle between three users of the popular Second Life online community, two of whom sued the holder of the avatar Patrick Leavitt after he tried to assert ownership over the usually tranquil virtual coastal village of Sailor’s Cove. In the end, the parties settled out of court, but Ross A Dannenberg, a senior partner at Banner & Witcoff and a founding chair of the Committee on Computer Games and Virtual Worlds of the American Bar Association’s Section of Intellectual Property Law, said after the case: “While Second Life may be a virtual world, the intellectual property is real, the contracts are real, and residents are still subject to real-world laws.” Avatar beware.—

LAWS TAKEAWAYS

LAWS TAKEAWAYS

IT IS CHANGING THE WAY LAW IS DONE

CLIENTS ARE DEMANDING FASTER, CHEAPER SERVICES

LAW MUST MEET THEIR DEMANDS

LAWYERS MUST:

Innovate

•

Invest

•

Get IT-savvy

•

Engage with the digital revolution

BUT, HOWEVER MUCH MACHINES CAN DO, THE WORLD WILL ALWAYS NEED HUMAN LAWYERS

Further reading

- The End of Lawyers? Rethinking the nature of legal services, by Professor Richard Susskind

- Inferring Multi-dimensional Ideal Points for US Supreme Court Justices

- National Science and Technology Council Report: Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence

- Artificial Intelligence in Law: The State of Play 2016

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only. Some information has been compiled by third party sources that we consider to be reliable. However, we do not guarantee and are not responsible for the accuracy of such. The views of third parties set out in this publication are not necessarily the views of IE University and they should be seen in the context of the time they were made.

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?

WANT TO DOWNLOAD THE EBOOK?